The obvious connection between this week’s Torah portion and haftarah reading is the message that God might strike dead even people who are doing God’s work, if they don’t get proper authorization for every action.

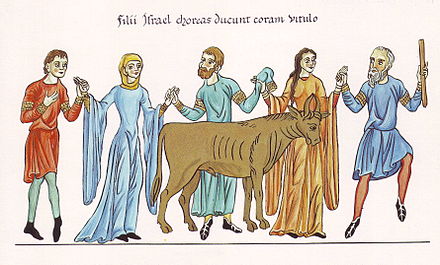

In the Torah portion, Shemini (Leviticus 9:1-11:47), two of Aaron’s sons who have just been consecrated as priests bring unauthorized incense into the sanctuary; God consumes their souls with fire.1 (See my post Shemini: Fire Meets Fire.) In the accompanying haftarah reading from the prophets, 2 Samuel 6:1-7:17, King David is transporting the ark on an ox cart to Jerusalem. Uzza, one of the two ad-hoc priests walking beside it, puts his hand on the ark to steady it when the oxen stumble; God strikes him dead “over the irreverence”.2 (See my post Shemini & 2 Samuel: Segregating the Holy.)

But Uzza’s death during King David’s first attempt to bring the ark to Jerusalem is not long enough for a haftarah portion. So the reading for this week continues with David’s second, successful transportation of the ark to his new capital. In this story, he dances in front of the ark wearing only a tabard called an eifod, and whenever he whirls his genitals are exposed. His wife Mikhal scolds him, but God apparently does not find David’s half-naked dancing irreverent; God punishes Mikhal with childlessness, but does nothing to David. (See my post Haftarat Shemini—2 Samuel: A Dangerous Spirit.)

The third story

A third story, which completes the haftarah, begins:

And it happened that the king was settled in his bayit, and God gave him rest from all the enemies around him. And the king said to Natan the Prophet: “See, please! I myself am dwelling in a bayit of cedar, and the ark of God is dwelling within the curtains [of a tent]!” (2 Samuel 7:1-2)

bayit (בַּיִת) = 1) house; any building where humans or a god reside at least part-time. 2) household; everyone who lives in the householder’s compound, including slaves as well as family members. 3) dynasty, lineage (like today’s House of Windsor).

Earlier in the haftarah, David brought the ark—considered God’s throne—into a tent he had pitched near his new cedar palace in Jerusalem.3 Now, when he says the ark is “dwelling within the curtains”, we learn that part of that tent is screened off from the main area with curtains, like the curtain that screened off the Holy of Holies in the portable tent sanctuary the Israelites built at Mount Sinai in the book of Exodus.

According to 11th-century commentator Rashi,4 King David thinks it is time to fulfill one of Moses’ commands in Deuteronomy about building a temple:

And you will cross the Jordan and settle in the land that God, your God, is allotting as your possession, and you have rest for yourselves from all your enemies from all around, and you dwell in safety, then it will become the place where God, your God, chooses [God’s] name to inhabit. There you must bring all that I command you, your rising-offerings and your slaughter-offerings … (Deuteronomy 12:10-11)

But 21st-century commentator Everett Fox wrote: “In the ancient Near East, such a desire would have been prompted not merely by piety; temples were political statements as well, symbolizing a god’s approval and protection of the regime.”5

King David’s motivations for building a temple could include a desire to welcome God at a higher level, a need to show everyone that Israel has its own powerful god, and a wish to leave a legacy in a world where he might lose the kingship like his predecessor, King Saul.

But David is foiled when the prophet Natan hears from God that night.

And that night, the word of God happened to Natan, saying: “Go and say to my servant David: Thus said God: Are you my builder of a bayit for me to stay in?” (2 Samuel 7:4-5)

Midrash Tehillim6 adds to the biblical story by adding to what God said, claiming that God refused to let David build the temple because he had “shed much blood”. This is probably not a reference to all the Philistines David killed when he was an Israelite general, but rather to David’s killing and looting when he was the leader of an outlaw band and worked for a Philistine king.7

Midrash Tehillim also points out that Psalm 30 begins: “A psalm song of the dedication of the bayit for David”. Therefore, the midrash says, even though David did not build the temple, it was named after him—“to teach you that whoever intends to perform a commandment but is prevented from doing so, the Holy One, blessed be He, credits him as if he had performed it.”8

But God gives Natan a different explanation in this week’s haftarah:

“For I have not stayed in a bayit from the day I brought up the Israelites from Egypt until this day; but I have been moving about in a tent and in a sanctuary. Wherever I have been moving about among the Israelites, have I ever spoken a word with one of the leaders of Israel whom I commanded to shepherd my people Israel, saying: Why didn’t you build me a bayit of cedar?” (2 Samuel 7:6-7)

Once again God has asked a rhetorical question whose answer is “No”.

“Now you must say thus to my servant David: Thus said the God of Armies: I myself took you from the pasture, from following the flock, to become ruler over the people, over Israel.” (2 Samuel 7:8)

When Natan repeats this to David, it will serve as a reminder both of how far he has come, and of how God is in charge. Next God affirms that the people will remain safe from enemies in the land David has finished conquering. Then comes a promise to David:

“And God declares to you that God will make a bayit for you.” (2 Samuel 7:11)

King David has already built his own cedar palace. Now God is promising a different kind of bayit for him: a dynasty.

“When your days [of life] are filled, and you lie with your forefathers, then I will raise up your seed after you, one who issued from your innards, and firmly establish his kingship. He will build a bayit for my name, and I will establish the throne of his kingship forever.” (2 Samuel 7:12-13)

David has not yet seen Batsheva at this time. But eventually David’s second child by Batsheva, Solomon, becomes the next king of Israel. Solomon does build a temple (bayit) dedicated God in Jerusalem.9 He is not as effective at building a dynasty (bayit) dedicated to God, and the northern half of his kingdom breaks away shortly after he dies. But kings from his line do rule Judah, the southern half of David and Solomon’s kingdom, until the Babylonian conquest over 200 years later.

Natan’s vision from God concludes with a reassurance that God will not replace David’s son with a new king, the way God replaced King Saul with David.

“I will be a father to him, and he will be a son to me. When he acts perversely, I will rebuke him with the rod of men and the affliction of humans. But my loyal kindness will not be removed from him as I removed it from Saul, whom I removed [to make room] for you. And your bayit and your kingship are confirmed forever before me; your throne will be established forever.” According to all these words and all this vision, thus Natan spoke to David. (2 Samuel 7:14-17)

In effect, God adopts David’s future son Solomon.

A qualification

What God does not say is that God’s promise to King David is contingent on the next king’s good behavior. In the first book of Kings, King Solomon completes the temple in Jerusalem and God fills it with a cloud of glory.10 Then Solomon makes a long speech to the assembled crowd, in which he says:

“And now, God of Israel, please let your word be confirmed that you promised to your servant David, my father.” (1 Kings 8:26)

Eight days later, after the people go home, God appears to King Solomon and says:

“And you, if you walk before me like your father David walked, with a whole heart and with uprightness, doing everything that I commanded you, keeping my decrees and my laws, then I will erect the throne of your kingship over Israel forever, as I spoke regarding your father David, saying: No one will cut you off from the throne of Israel. [But] if you actually turn away from me, you or your descendants, and do not keep my commands [and] decrees that I have set before you, and you go and serve other gods and bow down to them, then I will cut off Israel from the face of the soil that I gave them. And the bayit that I made holy to my name I will send away from my presence, and Israel will become a proverb and a taunt among all peoples.” (1 Kings 9:4-7)

Is the bayit that God made holy the temple? God hallowed it by filling it with the divine cloud of glory. But although God stay away from the temple, the physical building cannot be sent anwhere. A couple of centuries later, when the Babylonians loot and burn the temple,11 2 Kings and Jeremiah consider it a punishment for bad behavior.

What if the bayit that God made holy is the dynasty of King Solomon? Then the appearance of the cloud of glory shows that God has consecrated Solomon. And Solomon’s dynasty is “sent away from God’s presence” when the Babylonian army deports the last two kings of Judah, Jehoiachin and Zedekiah, to Babylon.

The yearning to leave a legacy, something that will last long after your death, is part of human nature. Parents hope their children’s children’s children will pass down their genes and their family history. Writers hope people will read their work after they are gone. Founders of businesses hope their companies will go on for decades without them.

The book of Ecclesiastes (Kohelet) notes:

The living know they will die. But the dead know nothing; they have no more reward, since even the memory of them is forgotten. Also their loves and their hates and their jealousies have already perished; and they have no share ever again in anything that is made under the sun. (Ecclesiastes 9:5-6)

King David does not get to build a bayit of cedar and stone to be God’s temple, but God consoles him with the promise that he will build a dynasty, a bayit of a royal line. But even that does not last forever.

- Leviticus 10:1-5.

- 2 Samuel 6:3-7.

- 2 Samuel 6:17.

- Rashi is the acronym of 11th-century Rabbi Shlomoh Yitzchaki.

- Everett Fox, The Early Prophets, Schocken Books, New York, 2014, p. 454.

- Midrash Tehillim on Psalm 62, 11th century.

- See 1 Samuel 27:8-12.

- Midrash Tehillim on Psalm 62. Translation from www.sefaria.org.

- 1 Kings 6:1-8:46.

- 1 Kings 8:10-11.

- 2 Kings 25:8-18.