A man who blasphemes the name of God is executed in this week’s Torah portion, Emor, in the book of Leviticus.

In English, “blasphemy” means insulting or showing contempt for a god, or for something sacred. In Biblical Hebrew, there is no word that exactly corresponds to “blasphemy”. Humans do not have the power to profane God, and our curses are only effective if God chooses to carry them out. We can, however, misuse sacred objects, making them chalal חָלַל = profaned, degraded by being used for an ordinary purpose. And we can insult or belittle God’s name, which is a type of blasphemy.1 In Biblical Hebrew, one’s name also means one’s reputation.

Yet the idea of reviling God or God’s name was so abominable to the ancient Israelites that the bible usually indicates blasphemy through euphemisms or near-synonyms.

Blasphemy with a euphemism in 1 Kings and Job

The verb barakh (בָּרַךְ), meaning to bless or utter a blessing, appears frequently in the Hebrew Bible. But twice in the first book of Kings and four times in the book of Job, this verb serves as a euphemism for blaspheming or cursing God.

In 1 Kings, Nabot owns a vineyard adjacent to palace of King Ahab. Ahab offers to buy the land, but Nabot refuses. The king is so upset that his wife, Jezebel, schemes to kill Nabot so she can seize the vineyard for her husband. She writes orders in the king’s name telling the judges of the town to summon Nabot.

“And seat two worthless men opposite him, and they must testify, saying: ‘Beirakhta God and king!’ Then take him out and stone him so he dies.” (1 Kings 21:10)

beirakhta (בֵּרַכְתָּ) = you “blessed”.

The judges follow orders. The two worthless men use exactly those words, and everyone knows they really mean that Nabot reviled God and the king. Nabot is executed by stoning.

At the beginning of the book of Job, Job is so devout he makes extra burnt offerings for his adult children, saying to himself:

“Perhaps my children are guilty, uveirakhu God in their hearts.” (Job 1:15)

uveirakhu (וּבֵרַכוּ) = and they “blessed”.

Job not only worries that his children might have some negative thoughts about God, but even uses a euphemism for blasphemy when he talks to himself.

The action of the story switches to the heavenly court of the “children of God”—perhaps lesser gods or angels. The God character mentions how upright and God-fearing Job is. The satan (שָׂטָן = adversary, accuser) in the court points out that God has blessed Job with wealth and children, so of course the man responds with grateful service. He adds:

“However, just stretch out your hand and afflict everything that is his. Surely yevarakhekha to your face!” (Job 1:11)

yevarakhekha (יְוָרַכֶךָּ) = he will “bless” you.

Thus the satan in the heavenly court also uses blessing as a euphemism for cursing God. The God character gives the satan permission to run the experiment, and in four simultaneous disasters Job loses his livestock, his servants, and all his children. Job responds:

“Y-H-V-H gave and Y-H-V-H took away. May the name of Y-H-V-H be a mevorakh.” Through all that, Job did not sin and did not accuse God of worthlessness. (Joab 1:21)

mevorakh (מְבֺרָךְ) = blessing.

Here Job actually does bless God’s four-letter personal name. He does not use the word for “bless” to revile or curse God.

The God character points out to the satan that Job’s devotion to God has not wavered. The satan replies:

“But a man will give up all that he has [to save] his life. However, just stretch out your hand and afflict his bones and his flesh. Surely yevarakhekha to your face!” (Job 2:5)

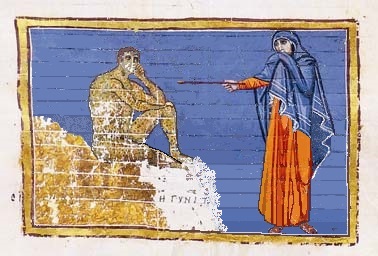

Again the satan uses blessing as a euphemism for blasphemy, and again the God character authorizes the experiment, asking only that the satan spare Job’s life. Job comes down with a painful inflammation from head to toe, and he sits in an ash-heap scratching himself.

Then Job’s wife utters her famous cry of despair, “Curse God and die!” But in the original Hebrew she expresses it this way:

“You still cling to your uprightness? Bareikh God and die!” (Job 2:9)

bareikh (בָּרֵךְ) = “bless!”

The reader or listener is expected to understand that “bless!” means the opposite, and should have the equivalent of air-quotes around it. Either Job’s wife does not want to go so far as to say “curse God” herself, or the author of the book does not.

Near-synonyms for blasphemy in Emor

People in the Hebrew Bible also commit blasphemy by using near-synonyms for “blaspheme”: verbs that mean curse, belittle, or revile, but count as blasphemy when they are applied to God or the name of God. The near-synonyms in this week’s Torah portion, Emor, are:

- nakav (נָקַב) = pierce, put a hole in, designate, curse,

- kalal (ַקַלַל) in the piel stem = belittle, insult, revile, curse.

One of God’s commands in the book of Exodus is:

Lo tekaleil God! (Exodus 22:27)

lo tekaleil (לֺא תְקַלֵּל) = you must not belittle, revile, curse. (lo, לֺא = not + tekaleil, תְקַלֵּל = you must belittle, insult, revile, curse; from the piel stem of the root verb kalal.)

Even though a human cannot actually inflict a curse on God, it is possible to belittle or revile God’s reputation. The word for “God” in this command is not God’s four-letter personal name, but Elohim (אֳלֺהִים) = God, a god, gods. The God of Israel does not want to be belittled or reviled by any name.

The command in Exodus is violated in this week’s Torah portion, Emor.

A son of an Israelite woman and an Egyptian man went out among the Israelites. And the Israelite woman’s son and an Israelite man scuffled in the camp. Vayikov the name, the Israelite woman’s son, vayekaleil, and he was brought to Moses. The name of his mother was Shelomit, daughter of Divri, from the tribe of Dan. (Leviticus 24:10-11)

vayikov (וַיִּקּב) = and he pierced, put a hole through, designated, cursed. (A form of the verb nakav.)

vayekaleil (וַיְקַלֵּל) = and he belittled, insulted, reviled, cursed. (A form of the root verb kalal in the piel stem.)

Does he curse God’s name? Or does he curse the Israelite man he is scuffling with, using God’s name in a curse formula?2 We do not know; this week’s Torah portion adds vayekaleil (and he belittled, reviled) without a direct object. But whatever Shelomit’s son says, we know he is misusing God’s name.

And they put him into custody [to wait] for exact information for themselves from the mouth of God. Then God spoke to Moses, saying: “Take hamekaleil outside the camp, and all who heard must lay their hands on his head. Then the whole community must stone him.” (Leviticus 24:12-14)

hamekaleil (הַמְקַלֵּל) = the belittler, the insulter, the reviler, the curser. (Also in the piel stem of the verb kalal.)

Moses and some of the other judges in the community have already determined, on the testimony of multiple witnesses, that Shelomit’s son is guilty. They wait only for God to tell Moses what the sentence should be, and God obliges.

Next God provides a general rule about blasphemy:

“And you must speak to the Israelites, saying: Anyone yekaleil his eloha will bear the burden of his guilt. Venokeiv the Name of God, he must definitely be put to death; the whole community must definitely stone him. Resident alien and native alike, benakvo the Name he must be put to death.” (Leviticus 24:15-16)

yekaleil (יְחַלֵּל) = who belittles, insults, reviles, curses. (Also in the piel stem of the verb kalal.)

eloha (אֱלֺהָ) = god. (Singular of Elohim.)

venokeiv (וְנֺקֵב) = and one who curses. (Another form of the verb nakav.)

benakvo (בְּנָקְבוֹ) = when he curses. (Also from nakav.)

One way to interpret this command is that anyonewho reviles his own god is guilty and will be punished in some undetermined way; but anyone who reviles the personal name of the God of Israel must be executed.

The Talmud (6th century C.E.) agrees that “For cursing the ineffable name of God, one is liable to be executed with a court-imposed death penalty.” But it interprets “anyone yekaleil his eloha” as anyone who reviles or curses one of the less sacred names of God, such as Elohim.3

Rashbam 4 wrote in the 12th century C.E. that God would deliver the punishment to someone who cursed a lesser name of God, so human judges did not need to take action.

The God character in the portion Emor immediately adds:

“And a man who strikes down the life of any human being, he must definitely be put to death.” (Leviticus 24:17)

There are other death penalties in the Torah, but this juxtaposition makes a point. Reviling God’s personal name is as bad as destroying a human being, who is made “in the image of God” (Genesis 1:27).

Shelomit’s son in this week’s Torah portion might have had a good reason for cursing God’s name. According to Sifra, a 4th-century C.E. commentary,

He had come to Moses asking him to render a judgment in his favor so that he could pitch his tent in the camp of Dan, his mother’s tribe. Moses ruled against him because of the regulation (Numbers 2:2) that the order of the encampment was to be strictly governed by the father’s ancestry. His resentment against the unfavorable ruling by Moses led him to blaspheme.5

In this addition to the biblical story, he curses when he is scuffling with an Israelite from the tribe of Dan who insults or excludes him.

I can sympathize with Shelomit’s son, and I think he should have been reprimanded, not executed, for expressing his anger with a curse.

Does it really matter if we give God a bad reputation? Ancient Israelite society depended on respect for God and therefore obedience to God’s laws, so reviling God could be an incitement to insurrection. Modern multicultural societies depend on obedience to civil laws and respect for those who follow different religions from your own. Today, I believe, it matters if we give a religion a bad reputation.

May we all bless, not curse, one another. And may we refrain from belittling or reviling any human being, for the sake of the divine image in every one of us.

- “God in principle cannot be hurt by any human act, but His name, available for manipulation and debasement in human linguistic practice, can suffer injury, and for this injury the death penalty is exacted, as here in the case of murder.” (Robert Alter, The Five Books of Moses, W.W. Norton & Co., New York, 2004, p. 652.)

- One example of a curse formula appears in Psalm 109:20: “May this be God’s repayment to my enemies …”

- Talmud Bavli, Shevuot 36a, translation by The William Davidson Talmud, www.sefaria.org.

- Rashbam is the acronym of 12th-century Rabbi Shmuel ben Meir.

- Translation by www.sefaria.org.