Sometimes a narrative section in the Torah flows as smoothly as a tale told by a master storyteller. Other times the narrative is a patchwork of different versions of the story, with obvious seams.

Those who believe that God dictated every word in the first five books of the bible to Moshe (“Moses” in English) either ignore the seams, or do some mental acrobatics to explain them away. I like to imagine that God’s dictation is interrupted when God gets distracted by other things happening in the world. But I daresay the single-author stalwarts would never accept a God who has trouble multi-tasking.

I prefer to explain the patchwork parts of Torah by applying a key hypothesis of modern source criticism: that several versions of the same story were circulating in ancient Israel when a redactor1 combined them to produce what became the authoritative version, the version recorded from then on in Torah scrolls. Sometimes the resulting narrative reads seamlessly. But some seams are definitely showing in the stitching together of last week’s Torah portion, Shemot (Exodus/Shemot 1:1-6:1) with this week’s Torah portion, Va-eira (Exodus/Shemot 6:2-9:35)—particularly regarding the question of who is qualified to speak for God.

Who speaks?

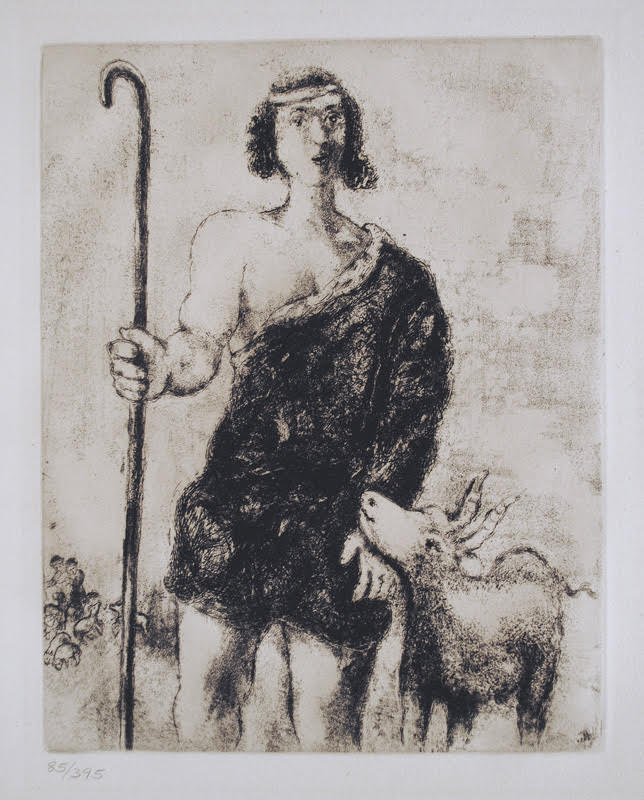

The first time Moshe goes to Mount Sinai, in the portion Shemot, he is a shepherd. He walks over to look at a bush that burns but is not consumed, and finds himself having a conversation with God—the God of his Israelite birth parents in Egypt. He learns that God plans to bring the oppressed Israelites out of Egypt and to the land of Canaan, and that he will be God’s agent.

Moshe tries five times to get out of this assignment. His penultimate attempt is to protest that he is a very poor speaker.

Then God said to him: “Who placed a mouth in the human being? … Is it not I, God? And now go! I myself will be with your mouth, and I will teach you what you will speak.” But he said: “Excuse me please, my lord. Please send by the hand of [someone] you should send!” (Exodus 4:11-12-13)

But God is not about to send someone else to liberate the Israelites. So God compromises, saying:

“Is not your brother Aharon the Levite? I know that he can certainly speak. And also, hey! He is going out to meet you, and he will see you and rejoice in his heart. And you will speak to him, and you will put the words in his mouth. And I myself will be with your mouth and with his mouth, and I will teach you both what you must do. And he will speak for you to the people. And he himself will be like a mouth for you, and you yourself will be like a god for him. And this staff, you will take it in your hand, because you will do the signs.” (Exodus 4:14-17)

In other words, Moshe will be God’s spokesperson, and Aharon will be Moshe’s spokesperson. Moshe will use his staff to initiate the miracles God has planned to impress first the Israelites, then the pharaoh.

Who holds the staff?

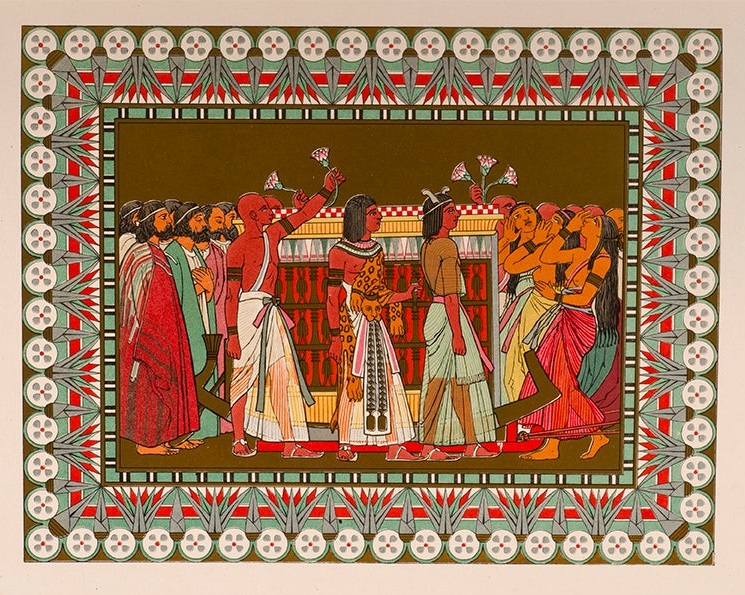

Moshe heads toward Egypt, and meets his brother at Mount Sinai. He tells Aharon everything he knows so far. Then both men go to Egypt and gather the Israelite elders.

And Aharon spoke all the words that God had spoken to Moshe, and he did the signs before the eyes of the people. And the people believed, and they paid attention … (Exodus 4:30-31)

Things seem to be going according to God’s plan. Next Moshe and Aharon go to the pharaoh and request that the Israelites get three days off work to go into the wilderness and sacrifice to their God. The pharaoh doubles their work instead, requiring them to find their own straw while still making their daily quota of bricks. The Israelite foremen blame Moshe and Aharon, and Moshe asks God:

“My lord, why did you do harm to this people? Why did you send me? Since I came to Paroh to speak in your name, he has done evil to this people; and you have certainly not rescued your people!” (Exodus 5:22-23)

Paroh (פַּּרְעֺה) =the title of the king of Egypt, “Pharaoh” in English. The portion Shemot ends with God saying the equivalent of “Just wait and see”.

Who memorizes the divine words?

The portion Va-eira then begins with God repeating what Moshe already learned on Mount Sinai. Then God says:

“Therefore, say to the Israelites: I am Y-H-V-H. I will bring you out from under the forced labor of Egypt, and I will rescue you from serving them, and I will redeem you with an outstretched arm and with great judgments. And I will take you for myself as a people, and I will be for you as a God, and you will know that I am GOD, your God, who brings you out from under the forced labor of Egypt. And I will bring you to the land where I raised my hand [in an oath] to give to Avraham, Yitzchak, and Yaakov, and I will give it to you as a possession. I am Y-H-V-H.” (Exodus 6:6-8)

This is quite a speech to memorize and deliver, for a man who knows he is a poor speaker. But the next verse says:

Then Moshe spoke thus to the Israelites. But they did not listen to Moshe, due to shortness of spirit and due to hard servitude. (Exodus 6:9)

In the portion Shemot, Moshe refused to speak to the Israelites without Aharon as an interpreter. But here in Va-eira, Moshe simply tells the people what God said—with no speech defect, no difficulty with Hebrew, no hesitation over the words. Aharon is not mentioned.

Classic commentary does not try to explain this sudden change. But the change makes sense if a redactor has suddenly switched to a different version of the story. Modern source scholarship identifies the story of Moshe’s recruitment on the mountain in the portion Shemot with a non-P (non-priestly) tradition.2 The version from the P tradition begins with Exodus 6:2, which is also the first verse of the portion Va-eira.

Clumsy lips

Right after the overworked Israelites ignore Moshe’s message, God orders Moshe to speak to the pharaoh. Moshe objects:

“Hey, the Israelites do not listen to me. Then how will Paroh listen to me? And I have foreskinned lips!” Then GOD spoke to Moshe and to Aharon, and commanded them regarding the Israelites and Paroh, king of Egypt—to bring out the Israelites from the land of Egypt.” (Exodus 6:12-13)

According to Richard Elliott Friedman, these two verses were added by a redactor.3 But why? Moshe and Aharon have already received God’s instructions. “Foreskinned lips” might indicate that Moshe’s problem as an orator is a speech defect, and the Israelites who were overworked and short of breath did not invest the energy to understand him. But there is no need to insert Moshe’s objection here, since he describes his lips that way again after an intermission giving Moshe and Aharon’s genealogy.

And GOD spoke to Moshe, saying: “I am GOD. Speak to Paroh, king of Egypt, everything that I speak to you.” And Moshe said before GOD: “Hey, I have foreskinned lips! So how will Paroh listen to me?” (Exodus 6:29-30)

Who speaks to the pharaoh?

In the P version of the story in the portion Va-eira, it appears that the whole conversation on Mount Sinai recorded in the portion Shemot never happened, because next God reacts to Moshe’s protest as if it were news, and tells Moshe the same solution God gave on Mount Sinai:

“See, I place you as a god to Paroh, and your brother Aharon will be your prophet. You yourself will speak everything that I command you, and your brother Aharon will speak to Paroh, and he will send out the Israelites from his land.” (Exodus 7:1-2)

Does this mean that from now on, God will speak to Moshe, Moshe will speak to Aharon, Aharon will speak to the pharaoh, and Moshe will initiate miracles with his staff—the same arrangement God decided on in the Mount Sinai version?

No.

First Moshe learns that God will harden the pharaoh’s heart after each miracle, so he will not let the Israelites go until God is ready to bring them out of Egypt. Then God gives instructions for a preliminary miracle:

“When Paroh speaks to you, saying: Give us a miracle for yourselves!—then you must say to Aharon: Take your staff and throw it down before Paroh; it will become a reptile.” (Exodus 7: 9)

Already Aharon is the brother wielding the staff.

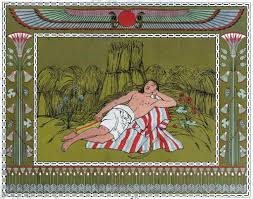

The first miracle that affects the whole country is turning the water of the Nile River into blood. At God’s command, Moshe warns the pharaoh at length. Then Aharon strikes the surface of the river, and God turns the water into blood (Exodus 7:14-20).

The next miracle, frogs, goes the same way, with Moshe speaking to Pharaoh, and Aharon wielding his staff (Exodus 7:26-8:2). Pharaoh summons both of them and promises to release the Israelites if they plead with their God to remove the frogs. With no prompting from God, Moshe asks Pharaoh to name the day of the frog removal, and adds that the death of the frogs on that exact day will prove God’s unique power (Exodus 8:5-7). For someone who claimed in the portion Shemot that he was “not a man of words”,4 he is thinking on his feet and speaking eloquently and confidently.

Moshe continues to be the one who speaks to Pharaoh throughout the rest of the portion Va-eira. Aharon stretches out his staff to initiate the miraculous plague of gnats or lice (Exodus 8:12-13), but Moshe holds out his staff to initiate the plague of hail (Exodus 9:22-23). Regardless of who wields his staff, Moshe does all the talking—and continues through the last three miracles—locusts, darkness, and death of the firstborn—in the following Torah portion, Bo.

Throughout the narrative of the ten miracles or plagues, non-P sources alternate with P sources, according to modern source scholars. But the redactor of this section of narrative stitches together the two versions of the story seamlessly, maintaining Moshe as the prophet who speaks directly to the pharaoh, and showing his increasing confidence and authority.5

But in the narrative section from Moshe’s call to prophecy on Mount Sinai (in the portion Shemot) to the miracle of turning water into blood (in the portion Va-eira), the redactor hops between sources without harmonizing them.

I wish the redactor had used more care. It is not that hard to redact; every week I write a lot about the weekly Torah portion or haftarah reading, then go back and select which paragraphs I will actually use for my blog post, often rearranging them in the process. If something I have written does not fit the theme, I remove it and save it for another post. If one paragraph seems to contradict the section before it, I add an explanation. And if I actually do contradict myself, I think about it and start over!

However, I am only redacting my own writing. What if I had the job of combining two earlier stories that I viewed as equally sacred? Perhaps the redactor of this part of the book of Exodus could not bear to eliminate either the narrative that views Moshe as unable or unwilling to speak, or the narrative in which Moshe speaks eloquently to the pharaoh.

What would I do, faced with that dilemma? I would include both—but rearrange the passages slightly, and write a little extra material, to show that Moshe is gradually learning how to speak and gaining confidence.

- Although the current usage of “redact” usually focuses on making deletions from a piece of writing, biblical scholarship uses “redact” to mean selecting and arranging various pieces of writing to make a single document.

- Julius Wellhausen (1844–1918), formulated a “documentary hypothesis” identifying different passages in the Pentateuch (Genesis through Deuteronomy) as coming from one of four sources: J, E, P, and D. Source scholarship today abounds with disagreements about non-P sources, as well as different theories for dating P and other sources. But the consensus is that the P (priestly) source is different from all other sources and is clearly identifiable.

- Richard Elliott Friedman, the Bible with Sources Revealed, HarperCollins, New York, 2003, p. 128.

- Exodus 4:10. See my post Shemot: Not a Man of Words.

- See my post Shemot to Bo: Moses Finds his Voice.