During this week of Passover (Pesach, פֳּסַח), Jews have been gathered around tables to celebrate liberation. Our ceremony (seder, סֵדֶר) has fourteen steps, punctuated by four cups of wine. When we pour the fourth cup of wine for each person at the table, we also pour wine into a cup that has been standing untouched the whole evening: the cup of Elijah.

Then we stand up, and someone opens the door to invite Elijah inside to join us. (This is the second time we open the door during the seder; before the meal, we open it to invite “all who are hungry” to come in and eat with us.)

While we wait for Elijah, we read a short passage. The traditional reading, from the centuries when almost every non-Jew was an enemy, consists of three biblical quotations asking for God’s wrath to destroy the enemies of Jews:

Pour out your wrath on the nations that do not recognize you, and on kingdoms that do not proclaim your name; because they ate up Jacob and made his abode a desolation. (Psalm 79:6-7) Pour out on them your curse and let your rage engulf them. (Psalm 69:25) Pursue in rage, and annihilate them from under the heavens of God. (Lamentations 3:66)

The connection between this reading and Elijah is tenuous. However, Elijah is portrayed in a few stories from the first book of Kings as a wrathful zealot bent on destroying the worshipers of other gods.

Many modern seders replace this reading with something less dire that refers to biblical stories in which Elijah orders kings around, or rescues the unfortunate, or becomes an angel instead of dying.

After that, we sing a song with these words1 before we close the door:

Eliyahu, hanavi (Elijah the prophet)

Eliyahu, haTishbi (Elijah the Tishbite)

Eliyahu, Eliyahu, Eliyahu haGiladi (Elijah the Giladite)

Bimheirah veyameinu (Quickly, in our days)

Yavo eleinu (May he come to us)

Im moshiach ben David (With the anointed one, descendant of David)

Moshiach (מָשִׁיחַ) is “messiah” in English. The Christian story is that the messiah arrived over 2,000 years ago as Jesus. The Jewish story is that the messiah (or the messianic age) will not arrive until the whole world has become a place of peace, justice, kindness, and wisdom. So naturally Jews hope Moshiach will come during our lifetimes.

But why do we also call for Elijah to come to us? It depends on which characteristic of the prophet—or angel—we consider.

Elijah the wrathful zealot

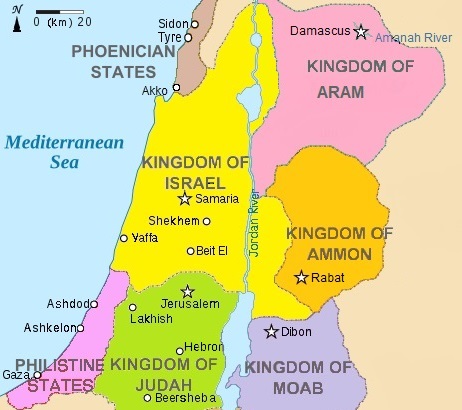

Elijah first appears in the Hebrew Bible after Ahab has become the king of the northern kingdom of Israel. Ahab marries the Phoenician princess Jezebel, and erects an altar for Baal and a pole for Asherah in his capital city, Samaria. The prophet Elijah is driven by his desire to eliminate the worship of other gods in the kingdom of Israel. First he declares a long drought, presumably so the Israelites will be realize their own God, Y-H-V-H, has the power to destroy them. After three years of drought, he stages a dramatic contest between Y-H-V-H and Baal at Mount Carmel.

When Elijah’s God wins, the Israelites prostrate themselves and shout:

“Y-H-V-H, he is the only god! Y-H-V-H, he is the only god!” Then Elijah said to them: “Seize the prophets of Baal! Don’t let any of them escape!” And they seized them, and Elijah took them down to the Wadi Kishon and slaughtered them there. (1 Kings 19:39-40)

Then God brings rain. (See my blog post: Haftarat Ki Tissa—1 Kings: Ecstatic versus Rational Prophets.)

Elijah’s zeal for God shows up again in a story about King Ahab’s successor, his son Achaziyahu. The new king falls out a window, and sends messengers to ask a god in Ekron whether he will recover. Elijah intercepts the messengers and tells them King Achaziyahu will die because he sought out a foreign god instead of asking a prophet of Y-H-V-H. The king sends fifty soldiers to arrest Elijah, and their captain climbs the hill where the prophet is sitting and orders him to come down. Elijah replies:

“If I am a man of God, fire will come down from the heavens and consume you and your fifty!” (2 Kings 1:10)

Obligingly, God incinerates the soldiers with fire from heaven. The king sends another fifty men, with the same result. The third time, the captain begs Elijah to please spare him and his men. No fire appears, and Elijah follows the captain to the palace, where he tells the king that he will not rise from his bed, but will die for his disloyalty to God. Achaziyahu dies.2

Elijah the insolent

Another approach to Elijah’s part of the Passover seder is to emphasize his refusal to submit to authority.

When Elijah first shows up in the bible, he is identified by his clan (Tishbi) and region (Gilead), as in the Passover song. Then, with no transition, he speaks abruptly to King Ahab.

Then Elijah the Tishbite, an inhabitant of Gilead, said to Ahab: “As Y-H-V-H lives, the God of Israel whom I wait on—there will be no dew nor rain these years unless my mouth pronounces it!” (1 Kings 17:1)

Whenever Elijah speaks to a king, he uses none of the customary courtesies. He never refers to himself as the king’s servant, nor says please, nor uses any honorifics. He does not respect human authority. (He also appears to be arrogant in his assumption that when he says a miracle will happen, God will follow through. But God always does. And when God gives him an order, Elijah always obeys.)

After three years of drought, God tells him:

“Go, appear to Ahab, and I will give rain to the face of the earth.” (1 Kings 18:1)

When he meets King Ahab outside the city of Samaria, Elijah criticizes him for following other gods, then gives him orders:

“And now, assemble all of Israel at Mount Carmel for me, along with the 450 prophets of Baal and the 400 prophets of Asherah who eat from Jezebel’s table.” (1 Kings 18:19)

King Ahab obeys.

Elijah the compassionate

The prophet Elijah is high-handed with kings, soldiers, and the prophets of other gods. But he is thoughtful when it comes to the unfortunate. Some seders tell the story of how he saved a poor widow and her son.

After Elijah announces the long drought, God tells him where to hide from the agents of King Ahab and Queen Jezebel. His second hiding place is the house of a widow and her son in a village near Phoenicia. When Elijah arrives, the widow tells him she has only enough flour and oil to bake a couple of biscuits3 before she and her son starve to death. Elijah tells her to make a small biscuit for him first, and promises that God will make a miracle so her jar never runs out of flour and her jug never runs out of oil until it rains again.4 The widow obeys the prophet, God makes the miracle, and Elijah lives in the room on the widow’s rooftop.

Then her son gets sick. When the boy stops breathing, Elijah carries him upstairs and lays him on his own bed.

Then he stretched himself out over the boy three times, and he called out to Y-H-V-H and said: “Y-H-V-H, my God, please bring back the life inside this boy!” (1 Kings 17:21)

The boy revives.

In a later story, Elijah is compassionate even when he is in despair, believing that he has failed in his mission to convert the whole kingdom of Israel to worshiping only Y-H-V-H. He heads south into the Negev, hoping to die there instead of at the hand of Queen Jezebel.5 On the way he thoughtfully leaves his servant in the town of Beersheba, so the man will not die in the desert with him.6

Elijah the angel

The final biblical story about Elijah describes his non-death. His disciple Elisha knows it is Elijah’s last day on earth, and sticks close to his master, even though Elijah asks him to stay behind three times. When they reach the Jordan River, Elijah rolls up his mantle (cloak) and slaps the water with it. The river divides and the two men walk across the riverbed.

And they kept on walking and talking. And hey! A chariot of fire and horses of fire! And they separated the two of them. And Elijah went up in a whirlwind to the heavens. (2 Kings 2:11)

Elisha watches, then picks up Elijah’s mantle.

According to later Jewish writings, Elijah becomes an angel (i.e. a supernatural messenger or emissary of God) after God’s whirlwind carries him up to the heavens. This concept first appears in the book of Malachi. In the third chapter God, addressing the Israelites, says:

“Here I am, sending my malakh; and he will clear the way before me, and suddenly the lord that you are seeking will come to the temple. And the malakh of the covenant that you desire, hey! He is coming!” (Malachi 3:1)

malakh (מַלְאַךְ) = messenger, emissary. When God sends a malakh, it is often translated into English as “angel”.

The text postpones identifying this malakh. The next verse warns that the arrival of God’s emissary is not all good news.

“But who can endure the day he comes? And who can stand when he appears? For he is like the fire of a smelter and the lye of a fuller.” (Malachi 3:2)

The book of Malachi ends with God announcing:

“Behold, I am sending you Elijah the prophet before the great and awesome day of Y-H-V-H comes. And he will turn the hearts of fathers toward sons, and the hearts of sons toward fathers, lest I come and I strike the land with complete destruction.” (Malachi 3:23-24)

Now we know the malakh or angel is Elijah, centuries after he ascended to the heavens. The “day of Y-H-V-H” is a day of final judgment anticipated in some later books of the Hebrew Bible and in the Talmud. After that “day”, those whom God has found acceptable will live in “the world to come”, in which the Moshiach reigns.

But first, Elijah will do what he can to improve people’s hearts so they can enter the world of the Moshiach.

The tradition that Elijah is still among us as a malakh continued from the Talmud to 19th-century Chassidic tales, in which Elijah appears disguised as an ordinary human being. He either rewards a good person or makes a man realize he has behaved badly and only later does the person realize it was Elijah.

This Elijah no longer despairs of reforming people, but enlightens them one at a time.

Which Elijah do you want to invite into your house—or into the world today? The zealot who wipes out people who are irredeemable? The insolent prophet who demonstrates that authority figures have less power than they think? The compassionate man who goes out of his way to save the lives of the unfortunate? Or the divine emissary who improves the world slowly, one person at a time, until Moshiach comes?

- Jews also sing this song during the ritual of Havdalah marking the end of Shabbat and the start of a new week.

- 2 Kings 1:2-17.

- The Hebrew word is translate here as “biscuit” is ugah, עֻגָה = a round, flat wheat cake baked on hot stones or ashes.

- 1 Kings 17:13-14.

- Jezebel sends a messenger to tell Elijah that she is going to kill him (1 Kings 19:1-2).

- 1 Kings 19:3.