When the Israelites arrive at Mount Sinai in the book of Exodus, they are led by God’s pillar of cloud by day and fire by night, as well as by God’s prophet Moses. When they leave in the book of Numbers, they are led by God’s cloud and fire, and Moses, and the ark.

It sounds like a net gain. But it was nearly a total loss.

Descent in Exodus

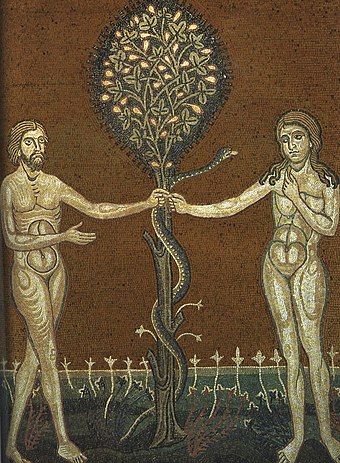

The Israelites, who spent their whole lives under Egyptian rule, are deeply insecure when they head into the wilderness. They cannot believe God will rescue them—from the Egyptian chariot army, from thirst, from hunger. After they reach Mount Sinai, God puts on an impressive revelation including fire, smoke, lightning, thunder, and shofar-blasts. The people tremble as violently as the mountain,1 and they unanimously pledge to do everything God commands.2

But all they really learn is that God is powerful, not that they can trust God to get them to Canaan and help them conquer it, as promised.

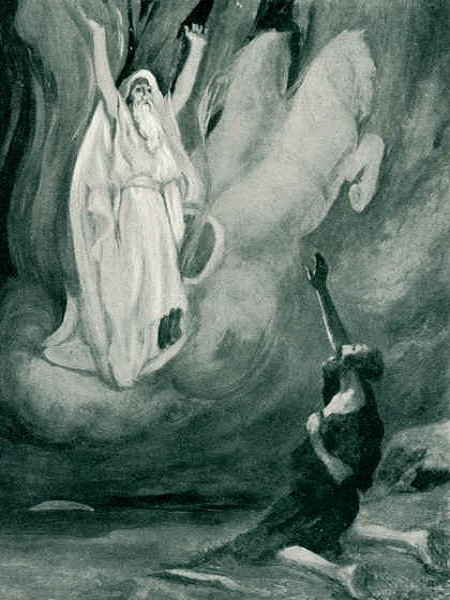

When Moses climbs Mount Sinai for his first forty-day stint, the presence of God at the summit looks like a cloud to him. But it looks like a “consuming fire” to the Israelites.3 How could anyone, even a prophet of Moses’ stature, come back out of that fire alive?

The Israelites below fall into despair in the Torah portion Ki Tisa (Exodus 30:11-34:36), just as God finishes giving instructions to Moses and inscribes some words on a pair of stone tablets.

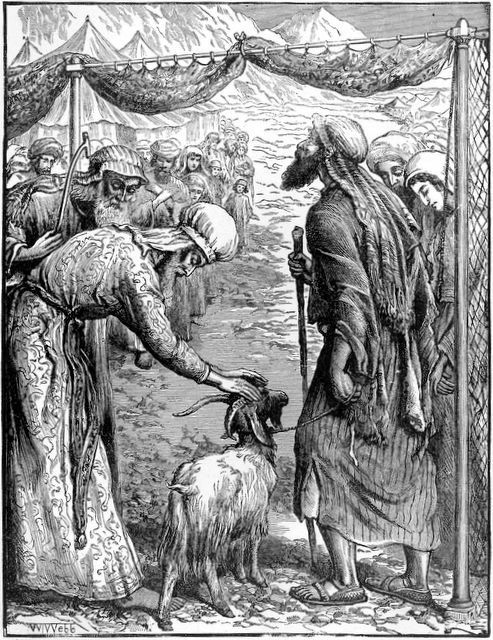

Then the people saw that Moses was delayed in coming down from the mountain, and the people assembled against Aaron and said to him: “Get up! Make us a god that will go in front of us, because this man Moses who brought us up from the land of Egypt, we do not know what has become of him!” (Exodus 32:1)

The Israelites are afraid to go any farther in the wilderness without Moses. Furthermore, God’s pillar of cloud and fire, which led the way to Mount Sinai,4 seems to have disappeared when they arrived.5 (Perhaps the divine pillar changed shape and relocated to the top of the mountain?) So, grasping at straws, they ask Aaron, Moses’ brother, to make them an idol “to go in front of us”. They would not expect a statue to walk, but they must hope that God would inhabit the idol, as the Egyptian gods inhabited statues in Egypt. Then if the idol were carried on a cart in front of them, God would, in a sense, be leading them. (See my posts Ki Tisa: Golden Calf, Stone Commandments and Ki Tisa: Making an Idol Out of Fear.)

Since the people “assembled against Aaron”, I suspect Aaron was telling them to wait a little longer for Moses to return. But now he caves in, and asks them to bring him gold earrings.

And he took [the gold] from their hands and he shaped it in a mold, and he made it into a statue of a calf. And they said: “This is your God, Israel, who brought you up from the land of Egypt!” And Aaron saw, and he built an altar in front of it. And Aaron called out and said: “A festival for Y-H-V-H tomorrow!” (Exodus 32:4-5)

The Israelites worship the golden calf as if the God of Israel, whose personal name is Y-H-V-H, were inhabiting it. Nobody mentions that God has already prohibited making or worshiping any statue.

On the mountaintop above, God tells Moses what is happening, and threatens to wipe out all the Israelites and make a nation out of Moses’ descendants instead. Moses talks God out of it. Then he carries the stone tablets down to the camp below—and smashes them. The Levites kill 3,000 calf-worshipers at Moses’ command. And God kills additional people with a plague.

After that, God tells Moses that the Israelites should still go north and conquer Canaan.

“And I will send a malakh in front of you, and I will drive out the Canaanites …. But I will not go up in your midst, lest I destroy you on the way, because you are a stiff-necked people.” (Exodus 33:1,3)

malakh (מַלְאָךְ) = messenger. (In most English translations, a malakh from God is called an angel. A divine malakh can look like a man, or look like fire, or be a disembodied voice.)

And [when] the people heard this bad news, they mourned, and not one man put on his ornaments. (Exodus 33:4)

Their human leader is with them again, but the people want their divine leader as well. How will they know that God is with them, and they are going the right way, unless God’s pillar of cloud and fire is in front of them?

Moses knows a malakh would not be enough to reassure the Israelites, so he tells God:

“If your presence is not going, don’t you make us go up from this [mountain]!” (Exodus 33:15)

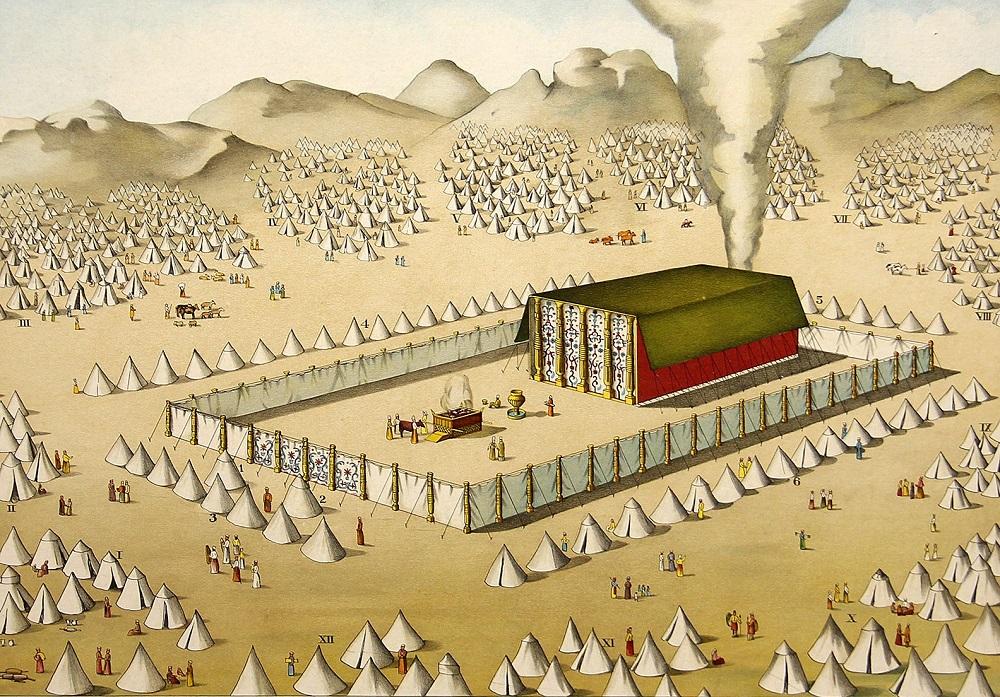

And God agrees to go with the Israelites for Moses’ sake. Only then does Moses pass on to the people the instructions God gave him for building a tent-sanctuary so God can dwell among them. The people eagerly donate materials and labor. They spend a year making everything, from the courtyard enclosure to the gold-plated ark inside the Holy of Holies. Then Moses assembles the sanctuary.

And Moses finished the work. And the cloud covered the Tent of Meeting, and the glory of Y-H-V-H filled the mishkan. (Exodus 40:33-34)

mishkan (מִשְׁכָּן) = Literally: dwelling-place (from the root verb shakhan, שָׁכַן = settle, stay, inhabit, dwell). In practice throughout the five books of the Torah: God’s dwelling-place, God’s sanctuary.

So God is willing to inhabit the tent-sanctuary, but not a gold statue. The book of Exodus ends:

For a cloud was over the mishkan by day, and fire was in it by night, in the sight of all the House of Israel on all their journeys. (Exodus 40:38)

Ascent in Numbers

The Israelites finally resume their journey to Canaan in this week’s Torah portion, Beha-alotkha (Numbers 8:1-12:16). Just before this Torah portion begins, the Torah indicates that unlike the golden calf, the two gold statues of keruvim (hybrid winged creatures) rising from the gold cover of the ark are not idols.

And when Moses came into the Tent of Meeting to speak with [God], then he heard the voice speaking to him from above the cover that was on the Ark of the Testimony, from between the two keruvim. (Numbers 7:89)

In other words, God speaks to Moses from the empty space between the two gold statues.

When the Israelites are finally ready to set out for Canaan, the Torah refers back to the end of Exodus.

And on the day the mishkan was erected, the cloud covered the mishkan for the Tent of the Testimony; and in the evening it was over the mishkan as an appearance of fire, until morning. Thus it was always: the cloud covered it, and appeared as fire at night. And according to when the cloud was lifted up from over the tent, after that the Israelites set out; and at the place where the cloud settled, there the Israelites camped. (Numbers 9:15-17)

The cloud by day and fire by night is not described as a pillar here; its shape is not mentioned at all. But it serves at least one of the purposes of the pillar of cloud and fire that led the Israelites from Egypt to Mount Sinai.

Whether for days or a month or a long time, when the cloud lingered over the mishkan, staying over it, the Israelites were camped, and they did not set out. But when it was lifted, they set out. (Numbers 9:22)

The other purpose of the pillar of cloud and fire was to indicate the direction of travel. This purpose is implied later in this week’s Torah portion:

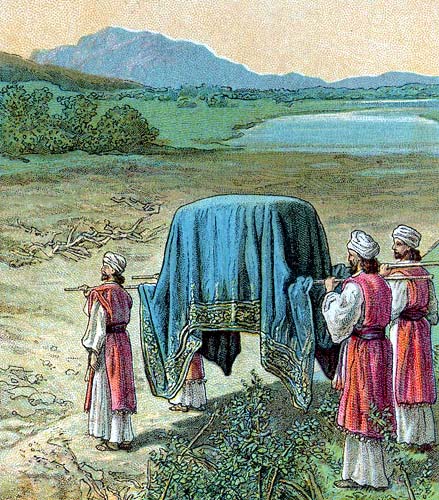

And they set out from the mountain of God on a journey of three days, and the ark of the Covenant of God traveled in front of them a journey of three days to seek out a resting place for them. (Numbers 10:33)

The ark, as we learned earlier in the book of Numbers, is covered by a curtain, a sheet of leather, a blue cloth, a crimson cloth, and another sheet of leather when the people travel6—both to honor it and to make sure nobody sees it. Levites from the clan of Geirshon carry it by the wood poles extending from the bottom of the ark.

The portion Beha-alokha contains two different descriptions of the location of the ark when the Israelites are traveling. First it describes the tribes of Judah, Yissachar, and Zevulun setting out, followed by Levites carrying the ark and other pieces of the mishkan.7 Then it says “the ark of the Covenant of God traveled in front of them”. Either way, the ark goes wherever the Levites gripping the poles take it, so how can it “seek out a resting place”?

And the cloud of God was above them by day, when they set out from the camp. (Numbers 10:34)

If the divine cloud hovers over the marching Israelites all day, then it could indicate the direction of travel by veering off. The Israelites would respond with a course correction—just as they did when the pillar of cloud by day and fire by night led them from Egypt to Mount Sinai.

And the cloud can still take the shape of a pillar. When God orders Moses, Miriam, and Aaron rto report to the entrance of the mishkan,

Then God came down in a pillar of cloud and stood at the entrance of the tent, and called: “Aaron and Miriam!” And the two of them went forward. (Numbers 12:5)

Thus God addresses the anxious insecurity of the Israelites by traveling with them in person, so to speak, in the form of the cloud above them. They also have Moses, the man who arranged their liberation from Egypt and who communicates regularly with God. And they have the ark as a symbol of God’s presence among them even when the mishkan is disassembled and God is not currently speaking to Moses from above the ark.

I have friends who want to believe God is leading them. None of them see pillars of cloud by day and fire by night, as far as I know. But they often notice signs and omens (what I would call coincidences) that reassure them God is in charge and they are being led in the right direction.

I don’t blame them, any more than I blame the Israelites marching toward the unknown dangers of the land of Canaan. The wilderness of this world is frightening.

- Exodus 19:16-18, 20:15-16.

- Exodus 24:3, 24:7.

- Exodus 24:15-18.

- Exodus 13:21-22.

- So many commentators conclude, since throughout their stay at Mount Sinai no pillar is mentioned until they have finished building the sanctuary. Then God’s cloud by day and fire by night settles on the sanctuary tent, and lifts to signal that it is time for them to travel on (Exodus 40:33-34-38).

- Numbers 4:5-8. See my post: Bemidbar: Covering the Sacred.

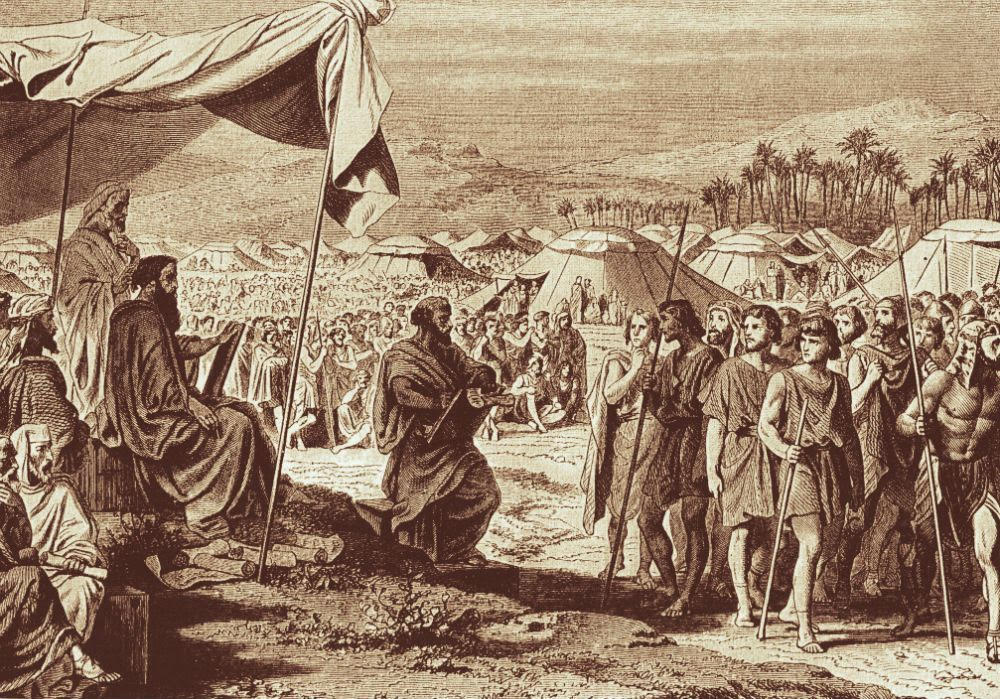

- Numbers 10:13-17.