Moses assembles the tent-sanctuary for God at Mount Sinai at the end of the book of Exodus. At the beginning of the book of Numbers, the people prepare to leave Mount Sinai and head to Canaan—with their portable tent-sanctuary, where God is present. So God gives instructions for dismantling, covering, and carrying all the pieces of the sanctuary in the first two Torah portions of the book of Numbers: last week’s portion, Bemidbar (Numbers 1:1-4:20), and this week’s portion, Naso (Numbers 4:21-7:89).

The priests must hide the holy objects inside the tent-sanctuary from view before the tent can be dismantled. Aaron and his two surviving sons must take down the curtain separating the Holy of Holies from the front chamber. They must cover the ark with the curtain, then add two more coverings. They also spread three coverings over the gold bread table, two over the gold lampstand, and two over the gold incense altar. The Levites are not allowed to touch, or even look at, these most sacred objects until they have been covered. Only they can they pick up the objects by their carrying poles and transport them to the next campsite.

The three priests must also cover the copper altar outside the tent.

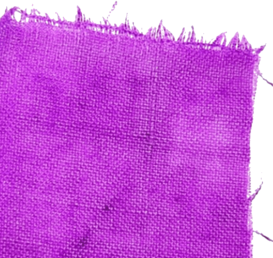

And they must clean fatty ashes off the mizbeiach, and they must spread a cloth of red-violet wool over it. And they must place upon [the cloth] all the utensils with which they serve at it: the cinder pails, the meat-forks and the scrapers, and the sprinkling basins, all the utensils of the mizbeiach. And they must spread out over them a cover of tachash skin, and they must place its carrying poles. (Numbers 4:13-14)

mizbeiach (מִזְבֵּחַ) = altar for offerings. (From the root verb zavach, זָבַח = slaughter livestock, make a slaughter offering. Altars were built of stone in Genesis and the first part of Exodus. Then God asked the Israelites to make a copper altar to stand in front of the new tent-sanctuary.)

tachash (תַחַשׁ) = an animal that has not been conclusively identified. Its skin must be fairly waterproof, since it is used as the top layer of the tent-sanctuary roof as well as one of the coverings of all the sacred objects the Levites carry when the Israelites are traveling.

Levites carry the altar

The second Torah portion in Numbers, Naso, opens with a census of the Levite clan of Gershon, then assigns its men aged 30 to 50 the duty of carrying the mizbeiach, the outdoor copper altar, as well as the swaths of fabric and skin hanging in (and on) the wooden frameworks of the tent and the courtyard wall.

This is the service of the clans of the Gershunites, for serving and for carrying: They must carry the cloths of the mishkan, and along with the Tent of Meeting its [cloth] covering and the tachash covering that is over on top of it, and the curtain at the entrance of the Tent of Meeting, and the hangings [enclosing] the courtyard, and the curtain at the entrance—the gate of the courtyard that is around the mishkan and the mizbeiach; and their cords, and all the equipment for their service. (Naso 4:24-26)

mishkan (מִשְׁכָּן) = dwelling place. (Usually God’s dwelling place, i.e. the portable sanctuary. From the root verb shakkan, שָׁכַן = settle, dwell, stay.)

During the 39 years the Israelites travel through the wilderness from Mount Sinai to the Jordan River, the mishkan and the Tent of Meeting are synonymous.

This is the service of the clans of the Gershunites regarding the Tent of Meeting, and their custody is in the hand of Itamar, son of Aaron the High Priest. (Numbers 4:28)

This week’s Torah portion assigns the remaining transport duties to two other divisions of Levites. The Kohatites will transport the holy furnishings inside the tent: the ark, table, lampstand, and incense altar. And the Merarites will transport the disassembled wooden frames of the tent and the courtyard wall.

Covering up

When the Israelites are encamped and the sanctuary is in place, only the priests are allowed to enter the Tent of Meeting. Only they may see the sacred objects inside. The Levites assist the priests outside the tent, and guard it from lay intruders. So it makes sense that the priests must cover objects inside, and insert their carrying-poles, before turning them over to the Kohatites to carry. That way, Levites cannot glimpse the sacred objects even when they are breaking camp. (See my post Bemidbar: Don’t Look.)

But why must the priests also cover the mizbeiach before it is carried off? The copper altar stands outside the Tent of Meeting. Everyone who enters the courtyard can see it. People bring animal and grain offerings right up to the altar, and watch the priests burn their offerings on it. The mizbeiach hardly needs to be hidden from sight when the Israelites are traveling.

Symbolic colors

The key, according to 19th-century Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch, is that the copper altar is covered with cloth dyed red-violet. Three colors of wool are used in the cloths the Israelite women weave for the mishkan and its courtyard: twilight blue (techeilet, תְכֵלֶת), red-violet (argaman, אַרְגָּמָן), and scarlet (tola-at shani, תוֹלַעַת שָׁנִי).1 Hirsch wrote that scarlet represents the color of blood, and therefore life at the animal level. Red-violet represents life at the higher, human level. And blue, the color of the sky, represents the limits of our horizon, the divine.

The most holy object, the ark, is covered first with the curtain that normally screens off the back room of the mishkan, the Holy of Holies; in the book of Exodus, this curtain is embroidered using all three colors of wool yarn, as well as fine linen.2 Then comes a layer of tachash skin, and after that a layer of wool cloth dyed with techeilet—an expensive blue dye made from murex sea snails.3. The first coverings over the bread table, the lampstand, and the incense altar are also wool dyed with techeilet. This blue, Hirsch wrote, is “close to God in highest holiness.”4

The first cloth covering the bread table is blue, but then after its utensils are placed on it, it is covered with a second cloth, this one scarlet. Hirsch explained, “The means of existence and prosperity are granted by God’s ‘Countenance,’ but all these ensure only “shani” [scarlet], animal-bodily life.”5

The copper altar, where the animal offerings are burned, does not get a layer of blue cloth. It is unique in that its first covering is red-violet wool.

Hirsch explained: “Argaman [red-violet], on the other hand, the higher, human level of life, is not granted by God. Rather, man must attain this level himself by freely mastering his own desires; he must harness all his animal-bodily powers and subordinate them to God’s will. This is symbolized by the offering altar and by the offering procedures performed on it.”6 Following Hirsch’s line of thought, the copper altar might be covered with red-violet cloth in order to illustrate that the sacrificial service at the altar is a method of achieving the human level, the level of free choice, which is symbolized by the red-violet color.

Honor

It is possible that the author of the Torah portions Bemidbar and Naso (which scholars attribute to the same Priestly source as most of Leviticus) found meanings in the colors of the coverings. But I propose a less symbolic explanation.

I think the priests cover the gold objects from inside the mishkan not only to prevent the Levites from seeing them, but also in order to treat God’s sacred objects with honor and respect. I can imagine them ceremonial spreading the blue cloth over each item.

They do not cover the copper outside altar with techeilet blue, but they do use cloth dyed with the next highest-ranking color. Red-violet cloth (also made from murex shells and also expensive) was used for the robes of the Kings of Midian and the seat of King Solomon’s throne.7 Covering the mizbeach with this royal color gives it honor and status. Using tachash skin as the top covering would also honor the altar, since the same kind of skin covers the roof of the mishkan.

When the Israelites are encamped, the mizabeiach is used to burn up the fat parts of cattle, sheep, and goats—and sometimes the entire animal—in order to make smoke rise to the heavens for God’s pleasure. This religious act is feasible only because God provides enough abundance so that surplus (mostly male) animals can be slaughtered and offered up.

Since the copper altar is used to honor God and thank God for abundance, it deserves to be honored itself. When the Israelites break camp, the priests honor the altar by draping an expensive royal red-violet cloth over it. This ritual was not as grand as the coronation of a king. But at least it was a way for the priests to show respect for God and their religion.

- See my post Bemidbar: Covering the Sacred.

- Numbers 4:5 and Exodus 26:31, 36:35.

- Numbers 4:7-11.

- Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch, The Hirsch Chumash: Bemidbar, translated by Daniel Haberman, Feldheim Publishers, Jerusalem, p. 51.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- The kings of Midian appear in Judges 8:26. King Solomon’s throne is in Song of Songs 3:10.