Every week of the year has its own Torah portion (a reading from the first five books of the Bible) and its own haftarah (an accompanying reading from the books of the prophets). This week the Torah portion is Shoftim (Deuteronomy 16:18-21:9) and the haftarah is Isaiah 51:12-52:12).

The second “book” of Isaiah (written in the sixth century B.C.E. around the end of the Babylonian exile, two centuries after the first half of Isaiah) opens:

Nachamu, nachamu My people!” (Isaiah 40:1)

nachamu (נַחֲמוּ) = Comfort them! (From the same root as nicham (נִחָם) = having a change of heart; regretting, or being comforted.)

This week’s haftarah from second Isaiah begins:

I, I am He who menacheim you. (Isaiah 51:12)

menacheim (מְנַחֵם) = is comforting.

At this point, many of the exiles in Babylon have given up on their old god and abandoned all hope of returning to Jerusalem. So second Isaiah repeatedly tries to reassure them and change their hearts; he or she uses a form of the root verb nicham eleven times.

In the Jewish calendar, this is the time of year when we, too, need comfort leading to a change of heart. So for the seven weeks between Tisha B’Av (the day of mourning for the fall of the temple in Jerusalem) and Rosh Hashanah (the celebration of the new year) we read seven haftarot of “consolation”, all from second Isaiah.

This year I notice that each of these seven haftarot not only urges the exiles to stick to their own religion and prepare to return to Jerusalem; it also coaxes them to consider different views of God.

The first week—

—in Haftarah for Ve-etchannan—Isaiah: Who Is Calling? we learned that once God desires to communicate comfort, the transmission of instructions to human prophets goes through divine “voices”, aspects of a God Who contains a variety ideas and purposes. When we feel persecuted, it may comfort us to remember that God is not single-mindedly out to get us, but is looking at a bigger picture.

The second week—

—in Haftarah for Eikev—Isaiah: Abandonment or Yearning? second Isaiah encourages the reluctant Jews in Babylon to think of Jerusalem as a mother missing her children, and of God as a rejected father. Instead of being told that God has compassion on us, we feel compassion for an anthropomorphic God. Feeling compassion for someone else can cause a change of heart in someone who is sunk in despair.

The third week—

—in Haftarah Re-eih—Isaiah: Song of the Abuser, we took a new look at what God would be like if God really were anthropomorphic. Like a slap in the face, this realization could radically change someone’s theological attitude.

The fourth week, this week—

—God not only declares Itself the one who comforts the exiled Israelites, but also announces a new divine name.

In Biblical Hebrew, as in English, “name” can also mean “reputation”. In this week’s haftarah, God mentions two earlier occasions when Israelites, the people God promised to protect, were nevertheless enslaved: when they were sojourning in Egypt, and when Assyria conquered the northern kingdom of Israel/Samaria. Both occasions gave God a bad reputation—a bad name. And the Torah portrays a God who is very concerned about “his” reputation. For example, when God threatens to kill all the Israelites for worshiping a golden calf, Moses talks God out of it by asking:

What would the Egyptians say? “He was bad; He brought them out to kill them in the mountains and to remove them from the face of the earth.” (Exodus/Shemot 32:12)

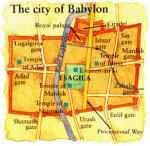

Now, God says, the Babylonians are the oppressors. They captured Jerusalem, razed God’s temple, deported all the leading families of Judah, and still refuse to let them leave Babylon.

Their oppressors mock them—declares God—

And constantly, all day, shemi is reviled. (Isaiah 52:5)

shemi (שְׁמִי) = my name.

The Babylonians are giving the God of Israel a bad name.

Therefore My people shall know shemi,

Therefore, on that day;

Because I myself am the one, hamedabeir. Here I am! (Isaiah 52:5-6)

hamedabeir (הַמְדַבֵּר) = the one who is speaking, the one who speaks, the speaker. (From the root verb diber (דִּבֶּר) = speak)

Since God’s old name has been reviled, God promises that the Israelites will know God by a new name. Then God identifies Itself not merely as the speaker of this verse, but as “the one, The Speaker”, adding extra emphasis with “Here I am!”

The concept of God as Hamedabeir appears elsewhere in the Bible. In the first chapter of the book of Genesis/Bereishit (a chapter that modern scholars suspect was written during the Babylonian exile), God speaks the world into being. Whatever God says, happens.

Second Isaiah not only refers to God as the creator of everything, but emphasizes that what God speaks into being is permanent.

Grass withers, flowers fall

But the davar of our God stands forever! (Isaiah 40:8)

davar (דָּבָר) = word, speech, thing, event. (Also from the root verb diber (דִּבֶּר) = speak.)

What is the davar of God regarding the exiles in Babylon? In this week’s haftarah second Isaiah says:

Be untroubled! Sing out together

Ruins of Jerusalem!

For God nicham His people;

He will redeem Jerusalem. (Isaiah 52:9)

nicham (ִנִחַם) = had a change of heart about; comforted.

God let the Babylonians punish the Israelites because they were unjust and because they worshiped other gods. But now God has had a change of heart and wants to end the punishment and rescue the Israelites from Babylon. Since God’s name was reviled, some of the exiles do not believe God has the power to carry out this desire. So God names Itself Hamedabeir and then declares:

Thus it is: My davar that issues from My mouth

Does not return to me empty-handed,

But performs my pleasure

And succeeds in what I send it to do.

For in celebration you shall leave,

And in security you shall be led. (Isaiah 55:11-12)

The speech of Hamedabeir achieves exactly what God wants it to. In this case, God wants the Israelites in Babylon to return joyfully and safely to Jerusalem. If the exiles believe this information, their hearts will change and they will be filled with new hope.

*

It is easy to give up on God when life looks bleak, and you blame an anthropomorphic god for making it that way. No wonder many Israelite exiles in the sixth century B.C.E. adopted the Babylonian religion. No wonder many people today adopt the religion of atheism.

But there is an alternative: redefine God. Discover a name for God that changes your view of reality, and therefore changes your heart.

Thinking of God as Hamedabeir, The Speaker, takes me in a different direction from second Isaiah. Not being a physicist, I take it on faith that one reality consists of the movement of sub-atomic particles. But another reality is the world we perceive directly with our senses, the world of the davar—the thing and the event. We human beings cannot help dividing our world into things and events. We are also designed to label everything we experience. What we cannot name does not clearly exist for us. In our own way, we too are speakers.

What if God is the ur-speech that creates things out of the dance of sub-atomic particles—for us and creatures like us?

What if God, The Speaker, is the source of meaning? Maybe God is what speaks to all human beings, a transcendent inner voice which we seldom hear. When we do hear The Speaker say something new, we often misinterpret it. Yet sometimes inspiration shines through.

I am comforted by the idea of a Speaker who makes meaning, even if I do not understand it.