And the Israelites came, the whole congregation, to the wilderness of Tzin on the first new moon, and the people stayed at Kadeish, and Miriam died there and she was buried there. (Numbers/Bemidbar 20:1)

It is the first new moon of the fortieth year since the Israelites left Egypt, and almost all of the adults in that exodus have died. They spend their final year in the wilderness traveling from the desert of the northern Sinai peninsula to the Jordan River in this week’s Torah portion, Chukat (Numbers 19:1-22:1).

The men of the new generation were all under twenty when they left Egypt with their parents. They reached the southern border of Canaan about two years later (including a long layover at Mount Sinai). But then their fathers refused to cross the ridge and attack the natives.1 God decreed that the Israelites would have to spend another 38 years in the wilderness, for a total of 40 years, while everyone who had refused to cross the border died—the entire older generation, except for Caleb and Joshua. Only then would God would let them conquer the land of Canaan.

During most of the waiting period they camped in the relative comfort of the oasis of Kadeish-Barnea in the northern Sinai peninsula.2 But thirty-eight years is a long time to spend waiting, and the people got cranky and restless. So did Moses, who did not even want the job of leading the Israelites in the first place when God recruited him at the age of 80.3

Now it is finally time to head for Canaan again. But this time they must cross a different border. Instead of returning to the southern border, the nest generation of Israelites must march east to Edom, then north along the east side of the Dead Sea until they reach the Jordan River, and see Canaan on the other side.

They set off across the wilderness of Tzin. But even before they reach Edom, things start to go wrong. First Miriam dies (presumably of natural causes, since at this point she is more than 130 years old). The Torah gives no details about the people’s reaction, but Miriam was a prophet and a leader in her own right, not merely the sister of Moses and Aaron, so she must have been universally mourned.

Whining about water

Next they camp in a place where there is no water. This has not happened since Exodus 17:1, when the Israelites camped at Refidim, the last stop before Mount Sinai.4 At Refidim, the older generation of Israelites demanded water from Moses, and complained:

“Why this bringing us up from Egypt [only to] to kill us and our children and our livestock with thirst?” (Exodus 17:3)

Now the younger generation makes a similar complaint.

And there was no water for the congregation; then they assembled against Moses and against Aaron. And the people quarreled with Moses, and they said: “If only we had expired when our kinsmen expired in front of God! Why have you brought God’s assembly to this wilderness to die there, we and our cattle? And why did you bring us up from Egypt to hand us over to this evil place, a place with no grain or figs or vines of pomegranates? And there is no water to drink!” (Numbers 20:2-5)

At least this generation of Israelites knows that it is God’s assembly. Yet the people complain against their human leaders, Moses and Aaron, who have no control over desert conditions. And 38 years after Refidim they still do not trust God to make sure they do not die of thirst.

At Refidim, back in the book of Exodus, God told Moses to take the staff he had used to initiate miracles in Egypt, and walk ahead to Mount Sinai with some of the Israelite elders.

“Here, I will be standing in front of you there on the rock at Chorev [Mount Sinai]. And you must strike the rock, and water will go out from it, and the people will drink.” And Moses did this before the eyes of the elders of Israel. (Exodus 17:6)

This time around, in the Torah portion Chukat, God gives Moses different instructions:

“Take the staff and assemble the community, you and your brother Aaron, and speak to the rock spur before their eyes, and it will give its water. And you will bring out water for them from the rock spur, and you will provide drink for the community and their beasts.” (Numbers 20:8)

The lack of water is real, and God calmly calls for a demonstration of divine compassion. But Moses is not listening carefully or thinking clearly—perhaps because he is still grieving for his sister. He takes the staff out of the sanctuary tent, where it has been kept “as a sign for recalcitrants”5 ever since God made it miraculously sprout and flower following the rebellions in the portion Korach. (See my post Korach: Quelling Rebellion, Part 2.)

Then in his emotional reaction to the current rebellion, Moses forgets that the flowering staff is supposed to remind rebels that God put Aaron and Moses in charge. He also forgets God’s command to speak to the rock, instead of hitting it like last time. Without thinking, Moses yells at the rebels and hits the rock with the staff.

And Moses and Aaron assembled the assembly in front of the rock spur, and he said to them: “Listen up, recalcitrants! Must we bring out water for you from this rock spur?” Then Moses raised his hand and struck the rock spur twice with his staff. And abundant water came out, and the community and its beasts drank. (Numbers 20:10-11)

Thus God exercises compassion and gives the people water even though they did not trust God to provide for them. The whining Israelites are off the hook—for now. But Moses should have trusted and followed God’s instructions to the letter, and when he started to say the wrong thing, Aaron should have intervened.

And God said to Moses and to Aaron: “Since lo he-emantem bi, to treat me as holy in the eyes of the Israelites, therefore you will not bring this assembly to the land that I have given them.” (Numbers 20:12)

lo he-emantem bi (לֺא־הֶאֱמַנְתֶּם בִּי) = you did not exhibit trust in me; you did not rely upon me. (Lo (לֺא) = not. He-emantem (הֶאֱמַנְתֶּם) = you believed, you considered reliable, you relied upon, you put trust in, you had faith. Bi (בִּי) = in me, on me.)

Perhaps there had been a tacit understanding that Caleb and Joshua were not the only two men from the old generation who would survive to enter Canaan. After all, why would God exclude Moses and Aaron, who had been equally loyal to God’s agenda at the southern border of Canaan?

Now God explicitly dooms Moses and Aaron to die without entering Canaan, on the grounds that they disobeyed God’s orders about getting water out of this second rock in the desert. Although the most likely cause of their disobedience was the emotional exhaustion that follows the death of a close family member, God points out that nevertheless they should have relied entirely on God’s orders to them.

In the past, Moses and Aaron have sometimes had good ideas that went beyond God’s instructions. And Moses has successfully argued with God for a change in a divine decree. Perhaps the lesson this time is that when they are not able to think clearly, their job is to simply follow God’s instructions to the letter.

Moaning about manna

The next part of the journey toward Canaan does not go well, either. Moses asks the king of Edom permission to go through his land, and promises that the Israelites will stay on the king’s highway, leave the fields untouched, and refrain from using any water from the wells. But the king of Edom refuses. So the Israelites have to circle around Edom and head north through the wilderness beyond Edom, land unclaimed by any country.

Next Aaron dies, and all the Israelites stop and mourn for him for thirty days. When they continue their journey skirting the kingdom of Edom, they get short-tempered.

… and the nefesh of the people became too short on the way. And the people spoke against God and against Moses: “Why did you bring us up from Egypt to die in the wilderness? For there is no bread and there is no water, and this wretched food makes our nefesh gag!” (Numbers 21:4-5)

nefesh (נֶפֶשׁ) = throat, appetite, animating soul, life, personality, mood.

The people’s comment that there is no water seems to be an automatic reflex; there is no indication of an actual water shortage. And their complaint that there is no bread does not mean there is an actual food shortage; they still get daily rations of manna from heaven—which they now call “wretched food”.

The Israelites are not in any danger. They are simply tired of the conditions they have endured all these years while dreaming of a better life in Canaan. And now, just when they are finally heading to Canaan, they discover they have to take the long way around. They are like young children who missed their nap and, as they are being dragged along by their parents, moan: “When are we ever going to get there? I’m hungry! I’m thirsty! It’s too far!”

Except that these children have lost two of their three “parents”. Aaron’s son Elazar replaced him as high priest, but out of the original three siblings who led them out of Egypt, only Moses is left.

The Israelites have not complained about the manna for 37 years. The last time was a disaster.6 This time, Moses does not even react. He is grieving for his brother now, as well as his sister. And he may feel overwhelmed with guilt, or perhaps bitterness, because God punished him for hitting the rock. He is in no condition to make any decisions.

But God, who exercised forbearance when the people complained about the absence of water in the desert of Tzin, does not hesitate to punish them this time.

Then God sent burning-serpents against the people, and they bit the people, and many of the Israelites died. (Numbers 21: 6)

The sadder but wiser Israelites realize they blew it again. They come to Moses and say:

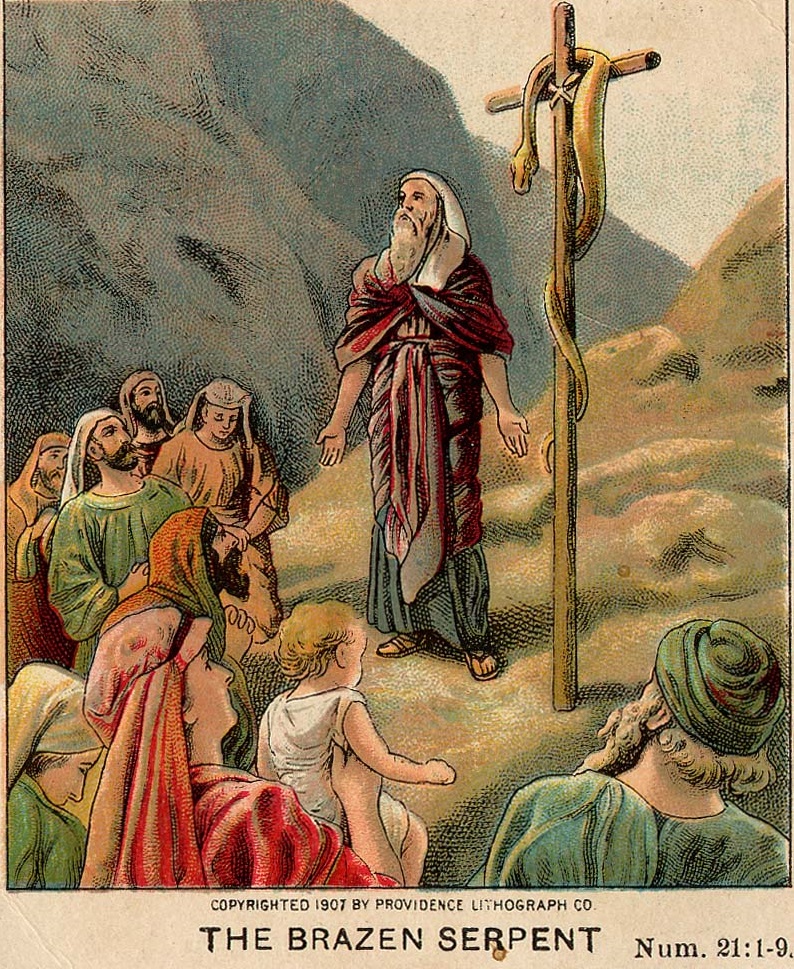

“We did wrong because we spoke against God and against you. Pray to God, and he might remove the serpent from upon us!” And Moses prayed for the benefit of the people. Then God said to Moses: “Make for yourself a burning-serpent and put it on a pole. And it will be that anyone who is bitten and sees it will live.” And Moses made a brass serpent and put it on the pole, and it happened: if a serpent bit a person and he looked at the brass serpent, he lived. (Numbers 21:7-9)

Even in his deep depression, Moses responds when his “children”, the human beings he is shepherding through the wilderness and its hazards, admit their error and ask him for help. He prays for them, and then follows God’s instructions for saving their lives.

Even worn-out children can learn from their mistakes. And even worn-out parents with their own woes, who are too exhausted to think straight, can rush to help someone with an actual need.

May we all receive extra strength when we are sapped of energy, so we can rise to meet the most important needs for ourselves and others.

- Numbers 13:31-14:35.

- See my post Shelach Lekha: Courage and Kindness.

- Exodus 3:11-18.

- The 38 years without complaints about water (but with plenty of complaints about other things) led to a story in the midrash that a magical well of water traveled along with Miriam, and disappeared when she died. This popular legend was recorded as early as the 2nd century C.E., in Sefer Olam Rabbah.

- Numbers 17:25.

- Numbers 11:5-34.