Laws about holiness and ritual purity fill most of the book of Leviticus. This week’s Torah portion, Emor (Leviticus 21:1-24:23), is no exception—but it does offer one story at the end, in order to illustrate a law about blasphemy.

In the middle of the Torah portion, God tells Moses to give the Israelites this law:

“You must not profane my holy sheim, so that I will be considered holy among the Israelites. I am God who makes you holy.” (Leviticus 22:32)

sheim (שֵׁם) = name, reputation.

Something is holy (kadosh, קָדוֹשׁ) in the Hebrew Bible when it is set apart from ordinary, mundane things and dedicated to God. Objects are holy when they are reserved for use in a religious ritual. Animals are holy when they are reserved as slaughter-offerings for God. Human beings are holy when they obey all of God’s rules for achieving holiness. God is holy by definition.

But what makes a name or a reputation holy? A sheim is not called holy unless it belongs to God. Both the names of God and God’s reputation must be treated reverently, neither denigrated nor used to swear a false oath.1 To profane God’s “name” is to sully God’s reputation, making God seem ordinary. The story at the end of the portion Emor illustrates how a half-Israelite man does just that.

The blasphemy

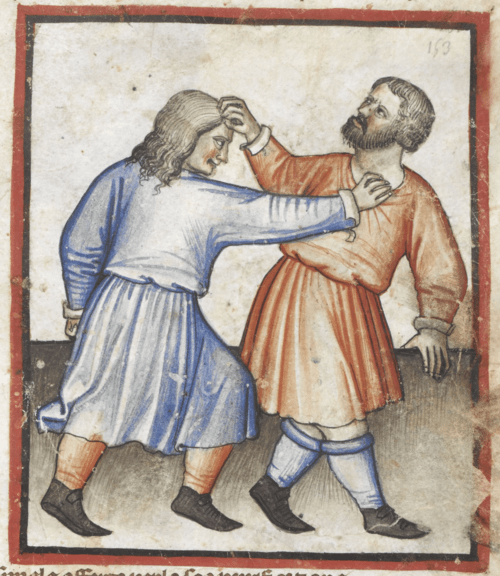

The son of an Israelite woman and an Egyptian man went out among the Israelites. And the son of the Israelite woman quarreled with an Israelite man concerning the camp. Vayikov, the son of the Israelite woman the sheim, vayekaleil. And they brought him to Moses. And the name of his mother was Shelomit … of the tribe of Dan. (Leviticus 24:10-11)

vayikov (וַיִּקֺּב) = pierced; cursed. (A form of the verb nakav, נָקַב = pierced, tunneled; designated; cursed.)

vayekaleil (וַיְקַלֵּל) = and he pronounced a curse, and he denigrated. (From the root verb kalal, קַלַּל = belittled, denigrated, cursed.)

When “the name” (hasheim, הַשֵׁם) is not followed by any other identifier, it means God’s sheim. Shelomit’s son has punched a hole through God’s name, profaning God’s reputation as holy. Then he cursed or denigrated someone, presumably the man with whom he quarreled concerning the camp. (For reasons why Shelomit’s son cursed his opponent, see my post Emor: Blasphemy.)

The consequence

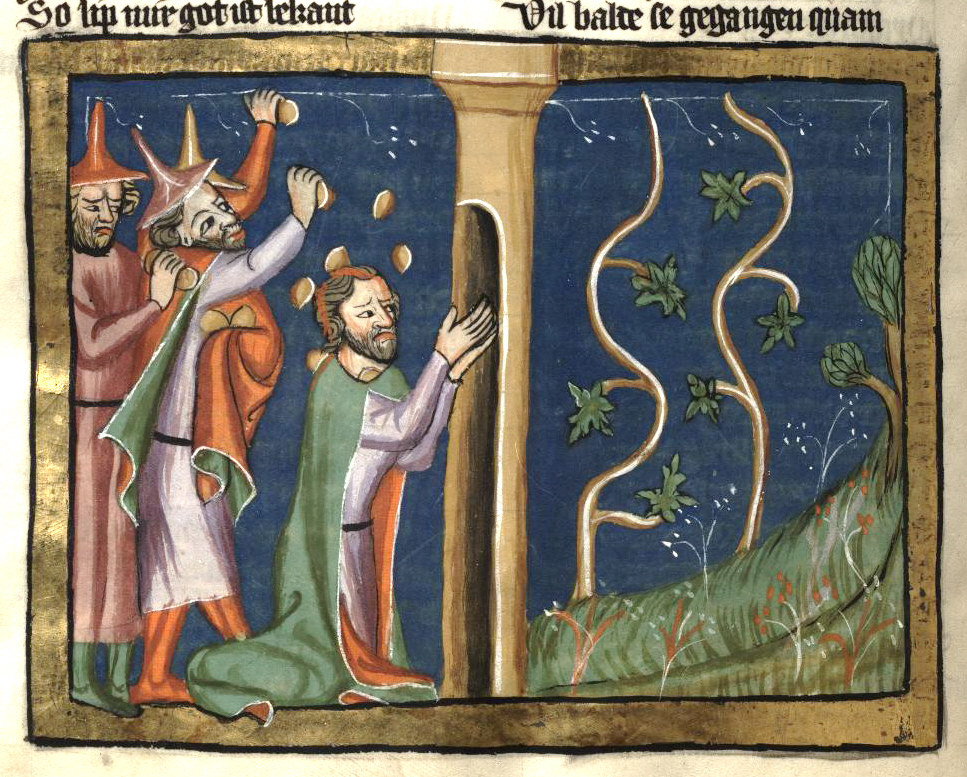

And they put him in custody, to get themselves a clarification from the mouth of God. God spoke to Moses, saying: “Remove hamekaleil to outside of the camp. Everyone who heard must lean their hands on his head, and then the entire assembly must stone him.” (Leviticus 24:12-14)

hamekaleil (הַמְקַלֵּל) = the one who pronounced a curse, the one who denigrated.

Belittling or cursing a human being does not carry the death penalty, but profaning God’s sheim does. And stoning is the most common form of execution in the Torah.

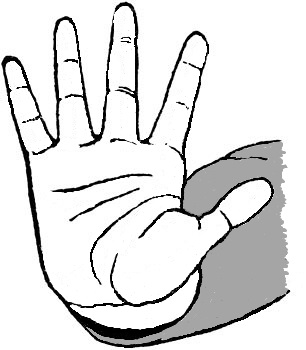

But why must everyone who heard the blasphemy lean (or lay) their hands on the blasphemer’s head first?

Laying on hands

When people are instructed to lay their hands on the head of a person or animal elsewhere in the Torah, the action indicates a transference of identity or agency from the person resting a hand on the head to the person or animal whose head is touched. The first time this action is described is in God’s instructions for consecrating the first priests and the first altar.

“Then you must lead the bull up in front of the Tent of Meeting, and Aaron and his sons must lean their hands on the head of the bull. The slaughter the bull in front of God, at the entrance of the Tent of Meeting.” (Exodus 29:10-11)

Moses must daub some of the bull’s blood on the four horns of the altar, then burn parts of the bull as an offering to remove any guilt the new priests might carry.

Laying a hand on the head of an animal before it is slaughtered at the altar becomes standard procedure for anyone who makes an animal offering. The book of Leviticus begins with the procedure for bringing a rising-offering, which is completely burned to make smoke for God.

And he must lean his hand on the head of the offering, so it will be accepted for him, to make reconciliation for him. (Leviticus 1:4)

The animal becomes a substitute for the animal’s owner; giving it to God (by slaughtering and burning it) symbolically gives the owner to God. According to Hebrew scholar Everett Fox,2 laying a hand on the animal’s head “may symbolize ownership, a statement of the reason for the sacrifice, or perhaps identification with the animal (as a substitute for the life of the worshiper).”

Laying hands on the heads of human beings normally transfers not identity, but authority. For example,3 when God tells Moses he will die before the Israelites cross the Jordan River into Canaan, Moses asks God to appoint a successor for him, so the people will not be leaderless.

And God said to Moses: “Take for yourself Joshua, son of Nun, a man who has spirit in him, and lean your hand upon him. … And place some of your majesty on him, so that the whole community of Israelites will heed him.” (Numbers 27:18, 20)

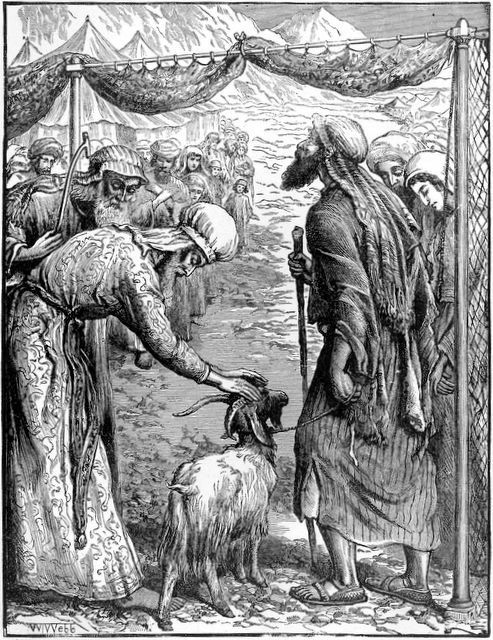

A third type of hand-leaning is prescribed for the annual ritual to make atonement with God and cleanse the entire community of sin on the day that became Yom Kippur. The high priest must place lots on two identical goats, and slaughter the one designated for God. He must sprinkle its blood on the ark inside the Holy of Holies and on the altar in order to purify them from contamination by the sins of the Israelites. Then he turns to the other goat.

And Aaron must lean both his hands on the head of the live goat and confess over it all the sins of the Israelites, and all their transgressions, for all their misdeeds, and place them on the head of the goat; and send it away to the wilderness by the hand of a designated man. And the goat will carry upon itself all of their sins to an inaccessible land … (Leviticus 16:21-22)

In this case, the guilt of the people is transferred to the goat when the high priest lays his hands on its head.

Is the death sentence for the son of the Egyptian man and Israelite woman the only time in the Hebrew Bible when hand-leaning does not effect any transference?

Passing it on

Rashi answered yes. When the witnesses lean their hands on the blasphemer’s head, he explained, they are indicating: “Your blood is on your own head! We are not to be punished for your death, for you brought this upon yourself!”4

According to this approach, still used by commentators today, leaning a hand on the blasphemer’s head is more like holding up a hand, palm forward, to say: Stop! Go no farther! You shall not pass!

For Rashi, the hand is a barrier, not an agent of transference. The witnesses are rejecting any responsibility for the son of Shelomit’s crime when he profaned God’s sheim while uttering his curse.

I would agree that the hand-leaning in the story from the portion Emor does not transfer the identity of the witnesses to the blasphemer. After all, he will be executed by stoning, not burned on the altar, so he is not anyone’s substitute gift to God. Neither do the witnesses transfer their authority to him, as Moses transferred his authority to Joshua by leaning a hand on his head.

However, the witnesses might be transferring their sins to the blasphemer, as the high priest Aaron transfers the sins of the Israelites to the head of the goat on Yom Kippur.

Chizkuni,6 a 13th-century Torah commentary, identifies one inevitable sin: that of pronouncing the words of the blasphemer’s curse. At the trial, the witnesses had to quote the words the blasphemer used. Therefore, “they transferred any guilt that they had been burdened with through that to the blasphemer”.5

But they might have been transferring other sins—or at least guilt for morally bad deeds. The Torah portion does not say so, but a close reading of the story reveals that the men with Israelite fathers have done wrong, even though they did not break the law. The quarrel between Shelomit’s son and the man with full Israelite parentage was “concerning the camp”. In the book of Numbers, campsites are allotted according to the father’s tribe.6 Since an Egyptian father is not a member of any Israelite tribe, his son would not be allowed to camp with his Israelite mother’s family in the area allotted to the tribe of Dan. Nor could he camp with any of the other tribes of Israel. He would have to live outside the camp, with the non-Israelite riff-raff and the people excluded because of skin disease.

Modern commentator David Kasher suggested that the blasphemer’s mother was probably raped by an Egyptian man who remained in Egypt. Their son could not live with his father. And none of the tribes would let him pitch his tent with them.

“… sure, by the strict letter of the law, he is guilty of a crime that merits the death penalty. Just as by the strict letter of the law, no tribe had to allow him to camp with them. But why didn’t they? How could they have turned him away? The law was on their side—but where was their compassion?”7

Kasher compared the witnesses laying hands on the blasphemer’s head to the high priest laying hands on the scapegoat’s head, and proposed that God required the witnesses to do this before the execution in order to force everyone who heard the quarrel to acknowledge their own guilt for refusing to help Shelomit’s son.

Yet the book of Leviticus generally ignores good traits like compassion, and instead focuses on laws, rules, and questions of purity versus contamination. So my guess is that the Israelites who hear Shelomit’s son curse God’s sheim in Leviticus would feel contaminated, impure. Laying their hands on the blasphemer’s head would symbolically transfer their contamination back to its source. Then when they kill him by stoning, their impurity and their sense of sin dies with him. Once they have followed the procedures for purification after contact with a corpse, the episode is over from their point of view.

Words have power. Hearing shocking words does psychologically contaminate the listener. Even today it is shocking, or at least sobering, to hear intentional blasphemy (rather than the common practice of adding the word “god” to an expletive as an intensifier).

What would it mean to deliberately denigrate God if you believed in God? And what would it mean to curse a human being if you believed your curse would be effective? How would you react if you heard a believer pronounce those words?

- See the second of the “Ten Commandments”, Exodus 20:7.

- Everett Fox, The Five Books of Moses, Schocken Books Inc., 1983, p. 511.

- Also see Numbers 8:10 and Deuteronomy 34:9.

- Rashi is the acronym of 11th-century commentator Rabbi Shlomoh Yitzchaki, who followed Torat Kohanim in this explanation. Translation by chabad.org.

- Chizkuni was written by Hezekiah ben Manoah and published in 1240. Translation by http://www.sefaria.org.

- Rabbi David Kasher, “The Curse: Parshat Emor”, ParshaNut blog post, reprinted in ParshaNut: 54 Journeys into the World of Torah Commentary, Quid Pro Books, 2020.

- Numbers 2:1-2.