Would you rather read a procedure manual or a story? This week’s double Torah portion, Tzaria and Metzora (Leviticus 12:1-15:32), provides a detailed manual for priests regarding a skin disease called tzaraat. But the two accompanying haftarah readings are stories about people with that disease.1

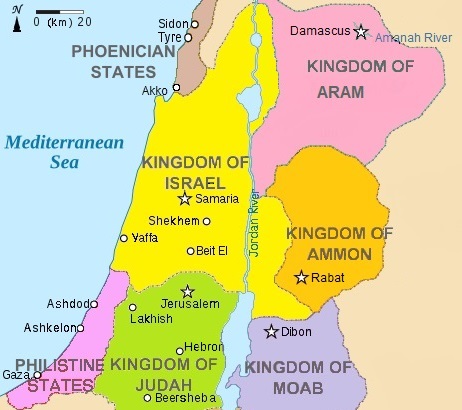

The haftarah for Tazria stars Naaman, a rich Aramaean army commander who goes to the kingdom of Israel to cure his tzaraat. He is healed only after he humbles himself to the prophet Elisha. (See my blog post: Tazria & 2 Kings: A Sign of Arrogance.) But without the kindness of his subordinates, his mission would have failed.

A kind servant: the Israelite girl

Those with power can use it to be benevolent to their subordinates. But how can subordinates be benevolent to their superiors? The story of Naaman gives two examples of servants who help their masters without exercising power. The first is an Israelite captive who has become a slave.

Naaman, commander of the army of the king of Aram, was a great man lifnei his master, and high in favor because through [Naaman] Y-H-V-H had granted victory to Aram. And the man was a powerful landowner metzora. And Aramaeans went out in raiding parties, and they brought back from the land of Israel a young adolescent girl, and she became lifnei Naaman’s wife. And she said to her mistress: “If only my master were lifnei the prophet who is in Samaria! Then he would take away his metzora.” (2 Kings 5:1-3)

lifnei (לִפְנֵי) = before, in front of, subordinate to. (The prefix le,לְ־ (to, toward, at, in relation to) + penei, פְּנֵי (face of—a form of the noun panim, פָּנִים= face, front). Therefore literally, lifnei = in relation to the face of.)

metzora (מְצֺרָע) = stricken with tzaraat (צָרַעַת), a skin disease (formerly and inaccurately translated as “leprosy”) characterized by one or more patches of scaly dead-white skin. These patches might also be streaked with red, and/or lower than the surrounding skin.2

Naaman is a very important person; he is subordinate to, lifnei, only the king of Aram. The captive young Israelite is a female slave, the most subservient rank in the Ancient Near East. She is subordinate to, lifnei, Naaman’s wife. A girl in her position might resent being seized by soldiers, taken to a foreign land, and forced to serve as a slave. She might well hate the husband of her mistress, who is a military commander and may even have led the raiding party that captured her.

On the other hand, most females in the Ancient Near East grew up expecting to be under the control of a male head of household, whether he was their father, husband, adult son (in the case of widows), or owner. Many girls in impoverished families were sold as slaves. The Israelite girl might be relieved that she is now living in comfort in a rich man’s house. And perhaps Naaman is true to his name, which means “Pleasant One” in Hebrew (from the root verb na-am, נָעַם = was pleasant, was agreeable.)

The Israelite girl is kind-hearted enough to wish that her master were cured of his skin disease, and she knows that tzaraat rarely heals. So she mentions a wonder-worker to her mistress: the prophet in Samaria, the capital of the kingdom of Israel. When she says “If only my master were lifnei the prophet!” her Aramaean mistress assumes she means “If only my master were in front of the prophet!”, and passes on the information to her husband.3

Refusing subordination: Naaman

In the kingdom of Israel, anyone whom a priest certifies as having tzaraat is ritually impure and must live outside their town until they recover (if ever). Being metzora is easier in Aram. The disease is not considered contagious; we learn later in the story that the king of Aram leans on Naaman’s arm when he goes into the temple of Rimon in Damascus.4 And tzaraat does not prevent Naaman from living in Damascus, the capital of Aram, or from leading his troops. Yet his skin disease is unsightly, and may be unpleasant in other ways as well. Naaman wants to be cured. So he takes chariots, horses, men, gifts, and a letter from his king to Israel.

And Naaman came with his horses and with his chariots, and he stood at the entrance of Elisha’s house. And Elisha sent to him a messenger saying: “Go, and you must bathe seven times in the Jordan. Then your flesh will be restored, and you will be ritually pure.” (2 Kings 5:9-10)

Just as the word lifnei sometimes indicates a subordinate position in Biblical Hebrew, someone who stands and waits in front of someone else is a subordinate (or is temporarily assuming a subordinate position as a polite gesture). Naaman arrives at Elisha’s house riding in a chariot, but when he stands waiting at the door he is in a subservient position. By refusing to see Naaman in person, Elisha underlines the idea that he outranks the Aramaean commander.

Then Naaman became enraged, and he went off and he said: “Hey, I thought he would certainly go and stand and call in the name of Y-H-V-H, his god, and wave his hand at the place, and he would take away the tzaraat. Aren’t Amanah and Farpar, the rivers of Damascus, better than all the waters of Israel? Couldn’t I bathe in them and become pure?” Vayefen and he went away in a rage. (2 Kings 5:11-12)

vayefen (וַיֶּפֶן) = and he faced away, and he turned away. (From the same root as panim and lifnei.)

Naaman knows he is a very important person. He expects the prophet to treat him as at least an equal.Elisha ought to invite the commander inside his house and stand waiting in front of him. After that, Naaman thinks, Elisha ought to personally wave his hand over the diseased patch of skin as he calls on his God.

In his resentment that Elisha is acting like his superior, Naaman also interprets Elisha’s order to bathe in the Jordan as an assertion that Israel’s river is superior to either of the two small rivers in Damascus.

Naaman is willing to be subordinate to the king of Aram, but not to the prophet in Israel. So he stops waiting lifnei Elisha’s door. He turns his face away in rejection.

More kind servants: Naaman’s retinue

When Naaman walks away, his own attendants try to make him see reason. They are not in a position to order him to follow Elisha’s orders. But they can offer a reasonable argument.

Then his attendants came forward and spoke to him, and they said: “Sir!” They said: “[If] the prophet said to you [to do] a big thing, wouldn’t you do it? And yet he only said to you: Bathe and be pure.” (2 Kings 5:13)

Naaman listens, swallows his pride, and does the sensible thing.

Then he went down and he dipped in the Jordan seven times, as the man of God had spoken. And his flesh came back like the flesh of an adolescent boy, and he was ritually pure. (2 Kings 5:14)

Choosing subordination: Naaman

Then he came back to the man of God, he and his whole camp [of men]. And he came and he stood waiting lefanav, and he said: “Hey! Please! I know that there is no god in the whole world unless it is in Israel. So now, please take a blessing from your servant!” (2 Kings 5:15)

lefanav (לְפָנָיו) = to his face, in front of him, subordinate to him.

When one important person in the bible speaks to another, he often calls himself “your servant” to be polite. Here Naaman also stands waiting in front of Elisha, in a subordinate position. And he acknowledges that he (and everyone else) is subordinate to the God of Israel.

Naaman has brought silver, gold, and ten outfits of expensive clothing5 to Samaria so he could pay the prophet for a cure. But now the two men stand in a different relationship. They are not buyer and seller, but a man of God and a witness of God’s power. So Naaman begs Elisha to accept a “blessing”. They both know he means a tangible gift, not just words of blessing.6

Choosing subordination: Elisha

But [Elisha] said: “By the life of Y-H-V-H, whom I stand waiting lefanav, if I take—” (2 Kings 5:16)

Elisha declares that he is subordinate only to God. His unfinished oath is a polite way of saying that he refuses to take anything from Naaman. Since Elisha works only for God, he does not sell his services. He caused Naaman’s healing in order to prove a point, not for any material benefit.

After the Elisha refuses Naaman’s second offer of a gift, Naaman asks him for a gift: as much dirt as two mules can carry. He explains that then he can go home to Aram and create a patch of Israelite ground where he can worship Elisha’s god. Naaman promises he will never sacrifice to any other god again, and hopes the God of Israel will forgive him for continuing to provide an arm for the king of Aram to lean on when the king enters the temple of Rimon.

And [Elisha] said to him: “Go in peace.” And he went away from him some distance. (2 Kings 5:19)

“Go in peace” is a polite way for a superior or father figure to give permission.7 Thus the haftarah ends with the new pecking order, in which Naaman has become a willing subordinate to God, and perhaps to God’s prophet Elisha, as well as to the king of Aram.

The insubordinate subordinate

Although the haftarah reading ends there, the story of Naaman continues in 2 Kings. Elisha’s servant Geihazi thinks his master was wrong about not taking anything from the rich Aramaean. So he runs after Naaman and his retinue. Naaman steps down from his chariot to greet him. And Geihazi lies to him, saying:

“My master sent me to say: Hey, now this: two adolescent boys just came to me from the hills of Efrayim, from the disciples of the prophets. Please give them a kikar of silver and two changes of clothing.” (2 Kings 5:22)

Geihazi does not dare claim that Elisha changed his mind and now wants the entire gift, but he is clever enough to invent a pretext for getting part of it. Naaman insists on giving him twice as much silver as he asked for, and dispatches two of his own servants to carry the clothes and the two bags of silver back to Samaria. At the city gate Geihazi takes the goods. If he had wanted to leave Elisha and set himself up with his own farm or business, he should have exchanged them at the marketplace then and there. Instead he brings the silver and clothing into Elisha’s house.

And he entered and he stood waiting before his master, and Elisha said to him: “From where, Geihazi?” (2 Kings 6:25)

Geihazi claims he did not go anywhere, but his master knows he is lying. Elisha accuses him of taking money from Naaman to buy things for himself, and adds:

“The tzaraat of Naaman will cling to you and to your descendants forever!” And [Geihazi] went away from lefanav, metzora like snow. (2 Kings 5:27)

Insubordination is not always punished so severely. Yet after rereading the whole story of Naaman, I am in favor of being a helpful subordinate, like Naaman’s attendants and his wife’s slave. If your superiors do you no harm, why not be kind and improve their lives—without stepping on their toes?

And if your superior is not benign, it is better to quit the job altogether than to lie and connive behind the boss’s back. Quitting is easier now, in a world where slavery has become rare, though finding a new job can still be hard. But if you do not respect your superior, you should still act so that you can respect yourself. Otherwise, even if your skin looks good, your soul will be disfigured.

- The haftarah for Metzora features four starving Israelites forced to live outside the city walls because of their disease. See my posts Haftarat Metzora—2 Kings: Insiders & Ousiders and Haftarat Metzora—2 Kings: A Response to Rejection.

- Leviticus 13:2-3, 13:10-22, 13:18-28, 13:42-44. Cf. Numbers 12:10-12.

- Ancient Aramaic and Biblical Hebrew are closely related Semitic languages, but it would take a while for the Israelite girl to master Aramaic, and nobody would expect her to express subtle shades of meaning.

- 2 Kings 5:18.

- 2 Kings 5:5. Cf. the fancy tunic Jacob gives Joseph in Genesis 37:3-4, and Joseph’s gifts of clothing to his brothers in Genesis 45:22.

- Cf. Jacob’s “blessing” to Esau in Genesis 33:11.

- 2 Kings 5:19.

- Cf. Exodus 4:18, where Moses’ father-in-law says it before Moses leaves him and returns to Egypt..

- 2 Kings 5:20-27.