Malakhi is the last book of the Prophets, written shortly after the second temple in Jerusalem was built (circa 516 BCE) and priests were once again burning offerings at the altar. But the priests were derelict in their duties, according to this week’s haftarah1 reading, Malakhi 1:1-2:7.

The book opens with God claiming credit for turning the kingdom of Edom into ruins, and warning that God can make Judea2 and its capital, Jerusalem, just as desolate. Why would God want to do that? Because the priests in Jerusalem are holding God’s “name” (i.e. reputation) in contempt.

And you say: “In what way have we held your name in contempt?” By bringing defiled food to my altar. And you say: “In what way have we defiled you?” By thinking God’s table can be despised. (Malakhi 1:6-7)

The altar is poetically called God’s table, as if God were eating the meat, even though the Hebrew Bible goes no farther than imagining that God enjoys the smell of the smoke from the altar.3

First God accuses the priests of offering animals that are defiled because they are blind, lame, or diseased. These offerings are strictly prohibited in the book of Leviticus, which orders:

Anything that has a blemish in it, you must not offer, since it will not be accepted for you. (Leviticus 22:20)4

The book of Malakhi emphasizes that God will not accept blemished offerings.

And if you offer the blind as a slaughter-sacrifice, it is not bad? And if you offer the lame or the diseased, it is not bad? Offer it, if you please, to your governor! Will he be pleased with you, or lift your face [acknowledge you favorably]? (Malakhi 1:8)

Burning defective animals on the altar is useless, God says. It would be better to shut the doors of the temple and let the fire on the altar go out.

I take no pleasure in you, said the God of Hosts, and I will accept no gift from your hands. (Malakhi 1:9)

Even the countries around Judea honor God more than the priests in Jerusalem.

My name is great among the nations, said the God of Hosts. But you profane it … And you say: “Hey, what a bother!” … And you bring the stolen, the lame, and the sick. (Malakhi 1:11-13)

Here God adds another category of gifts that only defile God’s altar: stolen animals. But then the book of Malakhi returns to the argument that a ruler does not want flawed animals:

A curse on the deceitful one who has [an unblemished] male in his flock, but he vows and slaughters some ruined one to my lord! Because I am a great king, said the God of Hosts, and my name is held in awe among the nations. (Malakhi 1:14)

Next comes a warning that God will curse the priests.

If you do not take heed and you do not set it in your heart to give honor to my name, said the God of Hosts, then I will send a curse upon you, and I will curse your blessings … (Malakhi 2:2)

These blessings, according to Rashi,5 include the grain, wine, and oil the priests receive from the people. The late Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz added that the it might mean “the blessings for which you pray, or the blessings with which you bless the people, the priestly benediction”.6 If the blessings that the priests pronounce backfired, then the people would despise the priests.

This week’s haftarah ends:

For the lips of a priest guard knowledge, and instruction is sought from his mouth; for he is a malakh of the God of Hosts. (Malakhi 2:7)

malakh (מַלְאַךְ) = messenger.

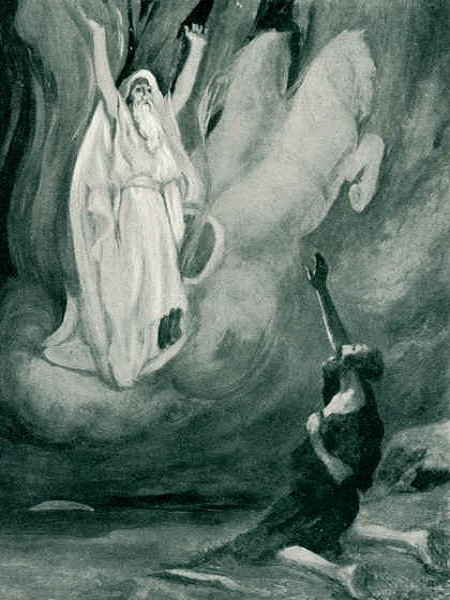

A malakh of God almost always turns out to be a divine being, or angel, as a manifestation of God. This verse is one of the rare exceptions. Rashi pointed out that both a divine malakh and a priest serve God and enter a holy place where God dwells.

There has been no temple in Jerusalem for almost two thousand years, and the distant descendants of priests have only minor roles in Jewish services. So why should we care whether the priests in the time of Malakhi were negligent? Does anything in this haftarah apply to us?

I think the underlying problem in the book of Malakhi is that the priests are two-faced. They maintain the appearance honoring God and doing their work reverently, when in reality they cut corners out of laziness (“Hey, what a bother!”—Malakhi 1:13). They even turn a blind eye to theft. Yet part of their job is to instruct the people about God’s laws!

The book of Malakhi gives an obvious example of this kind of deception. But it is easy to cheat when you are the boss, when you are responsible for work that affects others but does not mean much to you personally. If people who lead religious services today carefully follow the rules and rituals, and do whatever they can to make the services inspiring, then they are acting with integrity regarding their job—even if they are atheists. But if they ignore the rules, rush or plod through the services, and do a shoddy job, they are acting without integrity—whether they believe in God or not.

May we act with integrity in all the positions where we have authority, striving to do the job right, without cheating.

- Every week in the year is assigned a Torah portion (a reading from the first five books of the bible), and a haftarah (a reading from the Prophets).

- Malakhi was written after the Persian Empire had swallowed the Babylonian Empire, and Cyrus the Great had proclaimed that ethnic groups could rebuild their shrines and exercise limited self-governance in their provinces. The biblical books of Ezra and Nehemiah describe how those two leaders brought Israelites who had been held captive in Babylon back to the province of Judea, and rebuilt Jerusalem and its temple.

- See my post: Pinchas: Aromatherapy.

- See my post: Emor: Flawed Worship.

- Rashi is the acronym of 11th-century Rabbi Shlomoh Yitzhaki, whose commentary is still universally cited.

- Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz, Introductions to Tanakh: Malachi.