Salachtikha; I forgive you.

Joseph never says that. But then, no form of the verb salach, סָלַח (forgave) appears in the book of Genesis/Bereishit. When the word shows up elsewhere in the Bible, it is always God, not a human being, who forgives.

However, Joseph does know about pardoning, which men in command can do. In the Torah portion Vayeishev he interprets the dreams of two of his fellow inmates in an Egyptian prison. He tells one, the pharaoh’s chief cupbearer:

“In another three days the pharaoh yissa your head and he will restore you to your position and you will put the pharaoh’s cup on his palm…” (Genesis/Bereishit 40:13)

yissa (יִשָׂא) = he will lift. To lift up someone’s head is an idiom meaning “to pardon”. (A form of the root verb nasa, נָשָׂא = lifted, raised high, carried.)

Joseph then interprets the chief baker’s dream:

“In another three days the pharaoh yissa your head off you, and he will impale you on a pole and the birds will eat your flesh off you.” And it was the third day, the birthday of the pharaoh, and he made a banquet for all of his servants. Vayissa the head of the chief cupbearer and the head of the chief baker from among his servants. And he restored the chief cupbearer to bearing cups, and he put the pharaoh’s cup on his palm. But the chief baker he impaled… (Genesis 40:19-22)

vayissa (וַיִּשָּׁא) = and he lifted. (From the root verb nasa.)

The pharaoh lifts up the cupbearer’s head, pardoning him; but he lifts off the baker’s head, executing him.

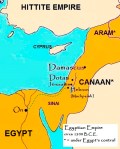

Two years later, Joseph is brought up from prison to interpret two dreams of the pharaoh, and by the end of their conversation the pharaoh has made Joseph the viceroy of Egypt.1

Joseph wants to forget his family back in Canaan, especially his ten older brothers, who hated him so much they were not able to speak to him in peace2, and his father, who was responsible both for creating the discord among his sons and for sending Joseph out alone to find and report back on his brothers. (See my post Mikeitz: Forgetting a Father.) The brothers seized him, threw him in a pit, then sold him as a slave to a caravan bound for Egypt.

When he sees his brothers again, Joseph is 37 years old and the viceroy of Egypt. He now has the power to execute his brothers or to pardon them.

He decides to test them first. He overhears them express remorse over how they treated their younger brother Joseph. Then Joseph puts the brothers through a series of tests, and concludes that they have indeed changed. (See my post Mikeitz & Vayiggash: Testing.) The tests are mysterious to Joseph’s brothers because they do not recognize him; they assume their younger brother died as a slave, and the viceroy is an Egyptian.

The conditions are ripe for forgiveness; Joseph’s older brothers have expressed remorse, and he can now trust them not to harm him or his younger brother Benjamin. But does Joseph ever forgive—or at least pardon—his brothers? Does he forgive his father for putting him in danger?

Vayiggash: Does Joseph forgive his brothers?

Joseph reveals his identity to his brothers after they refuse to leave Egypt without Benjamin, the youngest of Jacob’s sons and the only one with the same mother as Joseph.

And Joseph said to his brothers: “I am Joseph. Is my father really still alive!” But his brothers were not able to answer him, because they were aghast before his face. (Genesis 45:3)

His brothers are too stunned, and perhaps terrified, to answer. The man who has absolute power over them is the man whom they once sold into slavery.

Meanwhile, Joseph realizes that events had to unfold this way, or his whole extended family would have starved to death during the famine. His brothers’ crime was necessary to get Joseph to Egypt, where God inspired him to interpret the pharaoh’s dreams and he became the viceroy in charge of the only food supply in the region.

“And now, don’t worry, and don’t be angry with yourselves that you sold me here, because God sent me ahead of you to preserve life. For this pair of years the famine has been in the land, and for another five years there will be no plowing nor harvest. So God sent me ahead of you to set up food for you in the land and to keep you alive as a large group of survivors.” (Genesis 45:5-7)

By telling his older brothers not to worry or be angry with themselves over their crime, Joseph is telling them that the concept of guilt does not apply in their case. They are not responsible for their bad deed; God made them do it.

So now, you did not send me here, but God! And He has set me up as a father-figure to the pharaoh, and as the master of all his household, and as the ruler of all the land of Egypt. (Genesis/Berishit 45:8)

Now, Joseph thinks, he can be a hero and save everyone—his brothers, his father, and the whole extended family.

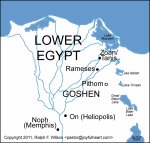

“Hurry and go up to my father and say to him: Thus said your son Joseph: God placed me as master of all Egypt. Come down to me, don’t stand still. And you shall dwell in the land of Goshen, and you shall be near me, you and your children and the children of your children, and your flocks and your herds and everything that is yours. And I will provide for you there …” (Genesis 45:9-11)

Although Joseph starts off attributing everything to God, he ends up promising that he, Joseph, will be a father-figure to his own family, as well as to the pharaoh. He is in charge.3 And he wants his actual father, Jacob, to be impressed by his long-lost son’s power.

“And you must tell my father about all my honor in Egypt, and all that you have seen. And you must hurry and bring my father down here.” (Genesis 45:13)

Having reduced his brothers to mere dependents, Joseph embraces Benjamin and weeps. Benjamin hugs him back, also weeping.

Then he kissed all his brothers and he wept upon them, and after that his brothers spoke to him. (Genesis 45:15)

Maybe now his older brothers can “speak to him in peace” because they no longer hate him. Or maybe their hatred has been replaced by fear. Benjamin, who was six years old and at home when the older brothers sold Joseph, can embrace his long-lost brother. But the ten older men merely speak; they neither cry, nor kiss Joseph, nor embrace him.

By denying that his brothers made a choice to sell him into slavery, Joseph shows that he does not respect them as adult human beings who are responsible for their own actions. Personally, I would rather admit a crime and apologize for it, than be silenced because my victim insists I had no freedom of choice.

As far as Joseph is concerned, he has absolved his older brothers of guilt and reconciled with him. But his brothers do not see it that way. Joseph’s speech allays their fear of retribution for a while, but it does not resolve their guilt.

Vayiggash: Does Joseph forgive his father?

Joseph sends his brothers back to Canaan with gifts, and his whole extended family moves to Egypt to live under Joseph’s protection.

Joseph hitched up his chariot and went up to Goshen to meet Israel [a.k.a. Jacob], his father. And he [Joseph] appeared to him, and he fell upon his neck, and he wept upon his neck a while. Then Israel said to Joseph: “I can die now, after seeing your face, [knowing] that you are still alive.” (Genesis 46:29-30)

Like many parents, Jacob does not know that he failed his son, so he does not apologize. Joseph could bring up what his father did 22 years before, and hope for an apology. (See my post Miketiz: Forgetting a Father.) Instead he treats Jacob the same way he treated the innocent Benjamin. There is no apology and no forgiveness; both father and son act as if their relationship is just fine.

This may be pragmatism on Joseph’s part. After all, Joseph has all the authority now, and he knows Jacob is not an insightful person. Why stir up old trouble?

Or Joseph may be thinking that if his father had not played favorites, then sent him alone into danger, he would never have been sold to the caravan headed for Egypt. Therefore God must have arranged Jacob’s behavior, too.

Vayechi: Does Joseph forgive his brothers after Jacob’s death?

Jacob dies in this week’s Torah portion, Vayechi (“and he lived”). Then his ten older sons become afraid that Joseph only restrained himself from executing them so as not to upset Jacob. In desperation, they invent a deathbed command.

And the brothers of Joseph saw that their father was dead, and they said: “What if Joseph bears a grudge against us and he indeed pays us back for all the evil that we rendered to him?” And they sent an order to Joseph saying: “Your father gave an order before he died, saying: Thus you shall say to Joseph: Please sa, please, the offense of your brothers and their guilt because of the evil they rendered to you. And now sa, please, the offense of the servants of the god of your father.” And Joseph wept over the words to him. (Genesis 50:15-17)

sa (שָׂא) = lift! (A form of the verb nasa.)

This communication proves that Joseph’s brothers did not feel pardoned or forgiven when he first told them that God arranged everything, including their crime.

And they do not feel safe with Joseph. Why should they? According to Joseph’s philosophy, anyone might become a puppet in God’s hands, deprived of free will. In such a universe, no one can be trusted.

On the other hand, if Joseph is wrong and humans do have a measure of free will, they still cannot trust Joseph.

Then his brothers even went and threw themselves down before him, and they said: “Here we are, your slaves.” And Joseph said to them: “Don’t be afraid! Am I instead of God?4 And you, you planned evil for me, but God planned it for good, in order to bring about this time of keeping many people alive.” (Genesis 50:18-20)

Joseph implies that only God can decide whether to punish the brothers. He also continues to make God responsible for his brothers’ crime. And although their false deathbed order explicitly begs Joseph to pardon—sa!—his brothers, he does not do so. Instead he says:

“And now, don’t be afraid; I, myself, will provide for you and your little ones.” And he comforted them and he spoke upon their hearts. (Genesis 50:21)

In the Torah, to speak upon someone’s heart is an idiom for changing that person’s feelings. (See my post Vayishlach: Change of Heart, Part 1.) Joseph both comforts his brothers and persuades them that he will continue to be responsible for their well-being. Even without a pardon, they finally trust Joseph.

Forgiveness or pardon is not the only road to reconciliation.

It’s a tall order, but I try to do better than Joseph. When people offer me apologies, explicitly or implicitly, I remember Joseph, and I am careful to accept them. Instead of saying merely, “It’s okay,” I say: “It’s okay, I forgive you.” I do not want anyone to suffer lingering guilt or uncertainty on my account.

On the other hand, if people wrong me or those I love, and they never admit it nor apologize, I struggle to forgive them. Sometimes I can reach a working relationship with them, but I never feel safe. Any reconciliation is incomplete.

May we all be blessed with a greater ability to be responsible for our own actions, to apologize, to forgive, and to change.

- Genesis 41:1-41.

- Genesis 37:4.

- Although Joseph is indeed second only to the pharaoh in power, he is not the absolute ruler he claims to be when he is bragging to his brothers. Later he has to ask the pharaoh for authorization for his family to settle in Goshen (Genesis 46:31-34) and for permission to leave Egypt to bury his father (Genesis 50:4-6).

- Jacob protested “Am I instead of God?” when Rachel, his second wife, has not become pregnant and she demands that Jacob give her children (Genesis 30:2, Vayeitzei).