The patriarch Yaakov (“Jacob” in English), also called Yisrael (“Israel”), dies in this week’s Torah portion, Vayechi (Genesis 47:28-50:26). King David dies in this week’s haftarah (reading from the Prophets), which is 1 Kings 2:1-12. Both dying men tell their heirs what to do after they have expired. But their instructions are about different kinds of unfinished business.

Choosing an executor

And the time drew near for Yisrael to die. And he called for his son Yoseif, and said to him— (Genesis 47:29)

Yoseif (“Joseph”) is Yaakov’s beloved eleventh son. Although normally a man’s oldest son inherits more of his estate, and responsibility for his family, Yoseif is the viceroy of Egypt and already takes care of his whole extended family, including his father. So Yaakov calls for Yoseif when he is approaching death.

And the time drew near for David to die. And he commanded his son Shlomoh, saying— (1 Kings 2:1)

Shlomoh (“Solomon” in English) is King David’s tenth son. While David is lying feebly in bed, his fourth son, Adoniyahu, gets himself anointed and proclaimed king without his father’s knowledge. (David’s oldest son, Amon, is already dead.) Batsheva (“Bathsheba”), David’s favored wife, and Natan, David’s prophet, rush into action. They get David to protest that his heir is Batsheva’s son Shlomoh, then get Shlomoh anointed and proclaimed king that same day. Adoniyahu’s supporters abandon him, and Shlomoh becomes king. (1 Kings 1:5-53) So David calls for Shlomoh when he is close to death.

Both Yaakov and David are practical in their choice of executor of their last wishes, choosing the son whom they trust and who has the most power to act.

Directions for burial

Yaakov’s first instruction to his son Yoseif is about his burial.

“If, please, I have found favor in your eyes, please place your hand under my thigh. And do with me loyal-kindness and faithfulness: do not, please, bury me in Egypt! [When] I lie down with my fathers, then carry me out of Egypt and bury me in their burial site!” (Genesis 47:29-30)

Yaakov’s deference to Yoseif shows that he knows he no longer has authority. Rabbi Chayim ibn Attar added: “Had he not said ‘please,’ it might have sounded as if he had not been grateful for the sustenance Joseph had provided thus far.”1

The request that Yoseif put a hand under his thigh (the most sacred way to swear an oath in the book of Genesis)2 shows Yaakov’s determination to be buried in Canaan.

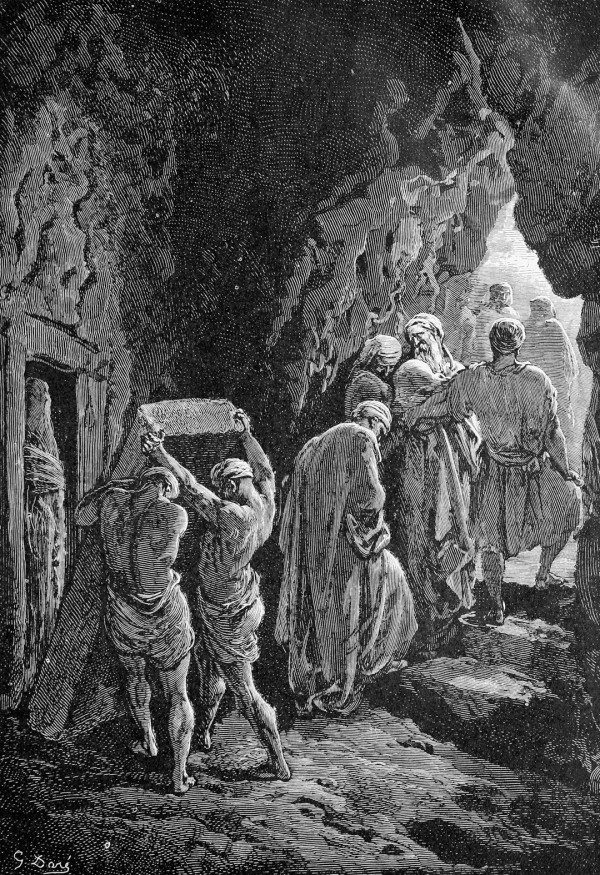

Lying down with one’s fathers and being gathered to one’s fathers are idioms for dying; in ancient Israel, family members were buried in the same cave for generations. Yaakov wants to be buried in “their burial site”—the cave of Makhpelah near Hebron.

Then he [Yoseif] said: “I myself will do according to your words”. But he [Yaakov] said: “Swear to me!” And he swore to him. Then Yisrael bowed, at the head of the bed. (Genesis 47:30-31)

The oath does turn out to be useful. When Yoseif asks Pharaoh permission for himself and his brothers to take Yaakov’s body to Canaan, he says: “My father made me swear …” and Pharaoh answers: “Go up and bury your father, as he had you swear.” (Genesis 50:5-6)

Why does Yaakov care about where he is buried? Rashi summarized a Talmudic-era midrash:

“Because its [Egypt’s] soil will ultimately become lice which would swarm beneath my body. Further, those who die outside the Land of Israel will not live again at the Resurrection except after the pain caused by the body rolling through underground-passages until it reaches the Holy Land. And another reason is that the Egyptians should not make me (my corpse or my tomb) the object of idolatrous worship.”3

S.R. Hirsch added a psychological reason: that after seventeen years in Egypt, Yaakov noticed that his whole family had come to think of Egypt as home. “It was sufficient reason for him to say to them: ‘You may hope and wish to live in Egypt, but I do not even want to be buried there.’”4

And Karen Armstrong pointed out that Yaakov wanted to continue the precedent set by his grandfather Avraham, who bought the burial cave—the first bit of land in Canaan owned by the family. Avraham and Sarah are buried there, along with Yaakov’s father Yitzchak (“Isaac”) and mother Rivkah (“Rebecca”), and his own first wife, Leah.

“Finally, Jacob gave instructions that he be buried not beside the beloved Rachel in Bethlehem but beside Leah in the family tomb at Hebron. For once, he did not allow himself to give in to his own inclinations but fulfilled his official patriarchal duty.”5

King David, however, gives his son Shlomoh no instructions regarding his burial—perhaps because he assumes his son will bury him in Jerusalem, where they both live. And King Shlomoh does.

Yaakov’s instructions for his estate

Yaakov’s health declines further, and Yoseif brings his two sons to receive a final blessing from their grandfather.

Then Yisrael gathered his strength and he sat up in the bed. (Genesis 48:2)

He tells Yoseif that back in Canaan, God appeared to him and told him:

“Here I am, making you fruitful and numerous, and I will appoint you as a congregation of peoples, and I will give this land to your descendants after you, as a possession forever!”(Genesis 48:4)

Yaakov now considers the promise of Canaan his estate, and he wants a say in how his descendants will divide up the land. So he tells Yoseif:

“And now your two sons, the ones born to you in the land of Egypt before I came to you in Egypt, they are mine; Efrayim and Menasheh, they will be mine like Reuven and Shimon!” (Genesis 48:5)

Reuven and Shimon (“Simeon” in English) are Yaakov’s first and second-born sons. In effect, adopting Efrayim and Menasheh gives Yoseif the double inheritance of the firstborn. Instead of getting one share, as Yoseif, he will get two shares, in the name of his two sons.

Yaakov starts talking about the death of Yoseif’s mother, Rachel, then notices the two people standing next to Yoseif. At this point, he is nearly blind.

And Yisrael saw Yosef’s sons, and he said: “Who are these?” And Yoseif said to his father: “They are my sons, whom God has given me here.” Then he said: “Please bring them to me, and I will bless them.” (Genesis 48:9)

Yaakov kisses and embraces his grandsons, overcome with emotion.

Then Yoseif took them away from his knees, and they bowed down, their noses to the ground. (Genesis 48:11)

In the Hebrew Bible, placing a newborn infant on one’s knees signifies an adoption.6 Although Yoseif’s sons are young men now, having been born before their grandfather came to Egypt seventeen years before, the symbolism may be the same.

The scribe who wrote down this part of the Torah portion had another reason for reassigning Yoseif’s portion of Canaan to Efrayim and Menasheh. From circa 900 to 720 B.C.E., the two kingdoms of Israel consisted of the territories of twelve tribes: ten tribes in the northern kingdom of Israel (Efrayim, Menasheh, Reuven, Shimon, Gad, Dan, Yissachar, Zevulun, Asher, and Naftali) and two tribes in the southern kingdom of Judah (Yehudah and Binyamin). Some scribes connected these twelve tribes with the twelve sons of Yaakov/Yisrael. To make the numbers work out, they assigned two tribes (Efrayim and Menasheh) to Yaakov’s eleventh son, Yoseif, and excluded the tribe of Yaakov’s third son, Levi, from the count, since the Levites were scattered throughout the two kingdoms and did not have a territory of their own.

As the book of Genesis draws to a close, Yaakov wants his family to return to Canaan, though he does not issue an explicit order about when they should go. According to the book of Exodus, Yaakov’s descendants stay in Egypt for 430 years before they finally head north.7

David’s instructions for execution

Dividing up territory is not a problem in the story of King David’s death, since David’s estate is the whole kingdom of Israel, before it separated into two kingdoms. David’s chosen son, Shlomoh, has already been anointed as king, so he gets the entire estate. But David has more to say to his son the king.

And the time drew near for David to die. And he commanded his son Shlomoh, saying: “I am going the way of all the earth. And you must be strong, and be a man!” (1 Kings 2:1-2)

When Yaakov gives his deathbed instructions to his son Yoseif, Yoseif is 57 years old and has been the viceroy of Egypt for 27 years. When David gives his deathbed instructions to his son Shlomoh, Shlomoh is about 20 years old and has barely begun his reign.

After reminding his son that he must follow God with all his mind and soul, David moves on to his primary concern: some unfinished business from his own reign.

First he orders Shlomoh to punish Yoav (“Joab” in English), David’s nephew and the general of his army. Yoav stealthily murdered the general of northern Israel, Avneir (“Abner”), right after David and Avneir had concluded a peace treaty in which the northern territories would join David’s kingdom. (See my post 2 Samuel: David the King.) Yoav’s motivation was revenge for his brother’s death at Avneir’s hands on the battlefield. The usual punishment for revenge killing was execution. But King David neither executed nor demoted Yoav—perhaps because of family feeling, or perhaps because he feared that Yoav was becoming too powerful to oppose.

Later, King David’s third son, Avshalom (“Absalom”), usurped the throne. David took refuge in Machanayim and sent out troops, but he asked Yoav and his other two commanders not to kill Avshalom. However, when Avshalom was snagged by a tree, and Yoav killed him.8 That was the last straw for King David, who then gave Amasa Yoav’s post as a commander.9 The next time Yoav and Amasa met, Yoav grabbed Amasa’s beard with one hand, and with the other hand stabbed him in the belly.10 Again King David did not punish his dangerous nephew; he even let Yoav become his general.

Now David wants Shlomoh to deliver the punishment that he could not manage during his own lifetime.

“… you yourself know what Yoav son of Tzeruyah did to me … to Avneir son of Neir, and to Amasa son of Yeter: he murdered them! … And you must act according to your chokhmah, and you must not let his gray head go down in peace to Sheol!” (1 Kings 2:5-6)

chokhmah (חׇכְמָה) = wisdom, technical skill, aptitude, experience, good sense.

Sheol (שְׁאוֹל) = the silent underworld where every person goes at death.

Next he tells Shlomoh to keep rewarding the sons of Barzilai, who fed David’s men during the war with Avshalom.11 Finally, he brings up Shimi son of Gera, who cursed and threw rocks at King David when he was fleeing Jerusalem after Avshalom’s coup. When David returned, he promised Shimi that he would not execute him.12 Now he regrets that promise.

“And now you must not exempt him from punishment! … you yourself know what you must do to him, and bring down his gray head in blood to Sheol!” Then David lay with his fathers, and he was buried in the City of David. (1 Kings 2:9-10)

David wants the execution of two men whom he had pardoned when he was king, and King Shlomoh does arrange their deaths—because he, too, does not trust Yoav, and because Shimi violated Shlomoh’s condition that he could live in peace as long as he did not leave Jerusalem.13

Today we still need to name an executor of our last will and testament. Like both Yaakov and David, many of us appoint one of our children, the one who has the most ability to carry out our wishes.

Few people today are in a position to leave a whole country as a bequest. But whatever we do leave is important to us: wealth to improve the lives of our heirs, heirlooms that have personal meaning to us, and sometimes instructions for more than our own burial.

We may believe that we can make sure everything happens the way we want it to after our deaths. But that is unrealistic. Our heirs will do as they think best, not as we think best.

At least Yaakov and David die knowing that their surviving children are doing well in life, and that the beloved children who will be their executors are successful and respected. So may it be for us today.

- Chayim ibn Attar, Or HaChayim, 18th century, translation in www.sefaria.org.

- See my post Vayechi, Chayei Sarah, & Vayishlach: A Touching Oath.

- Rashi (the acronym for 11th-century Rabbi Shlomoh Yitzchaki), summarizing Bereishit Rabbah 76:3, translation in www.sefaria.org.

- 19th-century rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch, reprinted in The Hirsch Chumash: Sefer Bereshis, English translation by Daniel Haberman, Feldheim Publishers, Jerusalem, 2002, p. 846.

- Karen Armstrong, In the Beginning, Ballantine Books, New York, 1997, pp. 115-16.

- Genesis 30:3-6, Ruth 4:16-17.

- Exodus 12:40.

- 2 Samuel 18:14.

- 2 Samuel 19:4.

- 2 Samuel 20:9-10.

- Barzilai appears in 2 Samuel 17:27-29 and 19:32-41.

- Shimi appears in 2 Samuel 16:5-10 and 19:20-25.

- See 1 Kings 2:28-35 on Yoav, and 1 Kings 2:36-46 on Shimi.