The book of Genesis/Bereishit begins with the creation of the world, then narrows in on one paternal line headed by Abraham. It ends with the death of Abraham’s great-grandson Joseph.

A name after death

The characters in the Torah do not hope for life after death.1 What men in the patriarchal society of the Ancient Near East seem to want most is male descendants to inherit their names and their land. (Names were inherited because instead of a modern last name, a man with the given name Aaron was called Aaron ben (father’s given name). If he had an illustrious grandfather, he was called Aaron ben (father’s given name) ben (grandfather’s given name).2)

Key blessings in the book of Genesis include:

“And I will make you a great nation, and I will bless you, and I will make your name great …” (Genesis 12:2, God to Abraham)

“Please look toward the heavens and count the stars, if you are able count them.” And [God] said to him: “So your zera will be!” (Genesis 15:5, God to Abraham)

zera (זֶרַע) = your seed, your offspring, your descendants.

“I will make your zera abundant as the stars of the heavens, and I will give to your zera all these lands, and all the nations of the earth will bless themselves by your zera.” (Genesis 26:4, God to Isaac)

“May God bless you and make you fruitful and numerous, and may you become an assembly of peoples.” (Genesis 28:3, Isaac to Jacob)

“Your zera will be like the dust of the earth, and you will spread out to the west and to the east and to the north and to the south.” (Genesis 28:14, God to Jacob)

In this week’s Torah portion, Vayechi (“And he lived”, Genesis 47:28-50:26, the last portion in the book of Genesis), Jacob concludes his deathbed blessing of two of his grandsons by saying:

“May [God] bless the boys, and may my name be called through them, and the name of my fathers Abraham and Isaac!”

Since descendants are so important, when the patriarchs Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob are approaching death they all leave something to their sons. But what they give their sons differs according to the personality of the father.

Abraham’s gifts

When Abraham is in his early 100’s, his behavior toward both his sons appalls me. He obeys when God tells him to disinherit and cast out his son Ishmael, along with the boy’s mother—and he sends them off into the desert with only some bread and a single skin of water. Since God has promised to make a nation out of Ishmael, he can assume his older son will survive, but why make him start a new life with so little? (See my post: Vayeira: Failure of Empathy.)

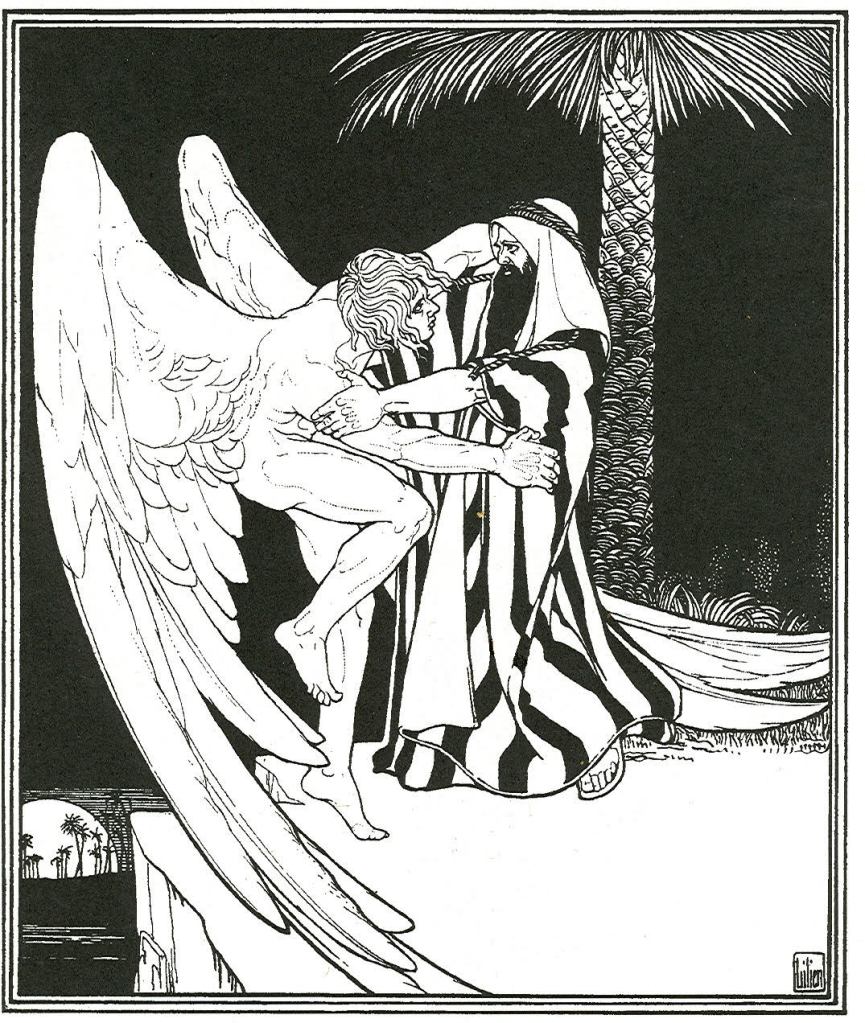

Some years later, Abraham hears God tell him to slaughter his son Isaac as a burnt offering. He neither argues with God, nor asks a single question. Isaac, a grown man, trusts his father and lets himself be bound on the altar. (Therefore Jews call this story the Akedah, the binding.) Only when Abraham’s knife is at his son’s throat does God call it off.3 But after God sends a ram as a substitute sacrifice, Isaac disappears from the story, and we never see him in the same place as his father again, not even at the funeral of Sarah, Abraham’s wife and Isaac’s mother. And although God blesses Abraham once more while the ram is burning, God does not speak to Abraham again after that.

During the remainder of his life, Abraham devises his own plans for the future, including buying a burial cave for the family after his wife Sarah dies,4 and arranging a marriage for Isaac. He is over 137 when he takes a new wife and sires six more sons. He then does some careful estate planning:

And Abraham gave everything that was his to Isaac. But to the sons of the concubines that Abraham had, Abraham gave gifts, and he sent them away from his son Isaac while he was still alive, eastward, to the land of the East. (Genesis 25:5-6)

He dies at age 175.

Then he expired. And Abraham died at a good old age, old and saveia; and he was gathered to his people. (Genesis 25:8)

saveia (שָׂבֵעַ) = full, satisfied, sated, satiated. (From the root verb sava, שָׂבַע = was satisfied, was satiated, had enough.)

He has a right to be satisfied; he has done his part to further God’s plan for Isaac’s descendants to inherit the land of Canaan, and he has also provided for his other children.

Isaac’s blessing

Like his father Abraham, Isaac does not own any land except for the burial cave, but he is wealthy in livestock and other movable property. He has two sons, the twins Esau and Jacob. By default, two-thirds of his property would go to his son Esau, who is older by a few seconds, while one-third would go to his son Jacob. Isaac does not makes any other arrangement for his estate.

Isaac is more interested in God than property. He takes care of his flocks, but unlike Abraham he makes no effort to increase them. He willingly lets Abraham tie him up as a sacrificial offering to God in the Akedah. And unlike Abraham, he pleads with God to let his long-childless wife conceive.5

At age 123, Isaac is blind and cannot stand up. He believes he will die soon, and he wants to deliver a formal deathbed blessing to at least one of his sons. Perhaps he views a blessing as a prayer, since the first of the three blessings he delivers begins “May God give you”, and the third begins “May God bless you”.6 What Isaac most wants his sons to inherit is God’s blessings.

Alas, his wife Rebecca does not trust him to give the right blessing to the right son, so she cooks up a deception that results in Jacob leaving home. Later Esau also leaves. But Isaac lingers on, presumably still blind and bedridden, until he finally dies at age 180.

Then Isaac expired. And he died, and he was gathered to his people, old useva in days. And his sons Esau and Jacob buried him. (Genesis 35:29)

useva (וּשְׂבַע) = and he was satisfied, and he was satiated, and he had had enough. (From the perfect form of the verb sava.) Although Isaac lives even longer than his father, the phrase “at a good old age” is not included in the description of his death. My best translation for the word useva in this verse is: “and he had had enough”. Isaac has spent more than enough time waiting for death.

Jacob’s blessings

Abraham focused on leaving his sons property. Isaac focused on leaving his sons blessings from God. Isaac’s son Jacob assigns both property and blessings at the end of his life, as well a prophecies and directions for his own burial.

He has twelve children, but he only cares about the two youngest, Joseph and Benjamin. His ten older sons sell Joseph as a slave bound for Egypt, then trick their father into believing that Joseph was killed by a wild beast. Jacob mourns for years. He is 130 years old when he finds out that Joseph is still alive and has become the viceroy of Egypt. He exclaims:

“Enough! My son Joseph is still alive. I will go and see him before I die!” (Genesis 45:28)

In this week’s Torah portion, Vayechi, Jacob lives for another 17 years in Egypt as Joseph’s dependent. It is unclear whether he has an estate to leave; does he still have some claim over the herds and flocks his other sons are tending? And could he still claim the land he purchased long ago at Shekhem, the town that his older sons destroyed?7

Although it is not clear what Jacob’s estate consists of, he gives Joseph the equivalent of a double portion of it by formally adopting Joseph’s two sons, Menasheh and Efrayim.8

Then, perhaps in imitation of his own father, Isaac, Jacob gives Menasheh and Efrayim blessings. In the first blessing he asks God to give them lots of descendants, and in the second he predicts that their descendants will bless their own children in their names.9

In the next scene, Jacob calls all his sons to his deathbed. To each one he delivers not a blessing, but a prophecy. Some of the prophecies refer to stories in Genesis about Jacob’s sons. Others have nothing to do with the characters in Genesis, but may refer to their eponymous tribes.10

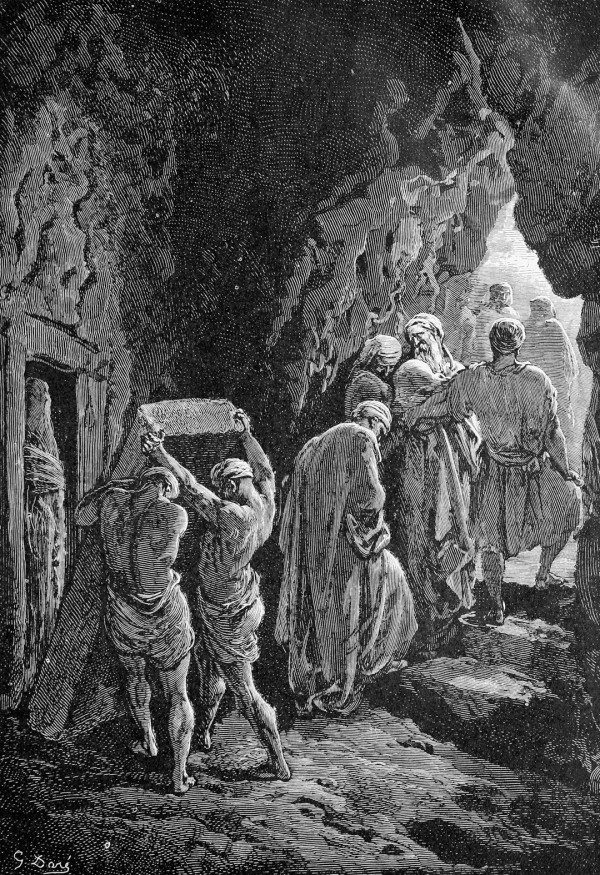

Before arranging his estate, giving blessings, and delivering prophecies, Jacob makes Joseph swear to bury him in Canaan, in the family burial cave. After he finishes his prophecies, he repeats these burial instructions to all his sons before he dies at age 147.11

Then Jacob finished directing his sons, and he gathered his feet into the mitah, and he expired, and he was gathered to his people. (Genesis 49:33)

mitah (מִטָּה) = bed of blankets. (From the same root as mateh, מַטֶּה = staff, stick, tribe.)

The text does not say that Jacob is satisfied or has had enough. But the sentence describing his death may imply that he gathered himself into the tribes he had created, before he was gathered by death. After Jacob dies, all twelve of his sons take his embalmed body up to the family burial cave in Canaan.

Although Jacob was selfish as a young man, cheating his brother out of his firstborn rights, at the end of his life he is absorbed with details concerning the future of the sons and grandsons he is leaving behind.

Joseph’s reminder

Twice Joseph tells his brothers that they should not feel guilty about selling him as a slave bound for Egypt because that was part of God’s master plan for bringing Jacob’s whole clan down to Egypt.12 (See my post: Vayigash & Vayechi: Forgiving?) On his deathbed, Jacob is still thinking about God’s master plan.

And Joseph said to his kinsmen: “I am dying, but God will definitely take account of you, and bring you up from this land to the land that [God] swore to Abraham, to Isaac, and to Jacob.” And Joseph made the sons of Israel swear, saying: “God will definitely take account of you; then bring up my bones from here!” And Joseph died, 110 years old. And they embalmed him and they put him in a coffin in Egypt. (Genesis 50:24-26)

Thus ends the book of Genesis. Joseph is not described as satisfied, or even as being gathered to his ancestors. He is focused not on his immediate family, but on the distant future of his whole clan. His only deathbed act is to make all the men in his family swear to pass on the information that someday his bones must be buried in Canaan. This promise will serve as a reminder that someday the descendants of Jacob, a.k.a. Israel, must return to the land that God promised to them.

I think Abraham believes his estate is important because he is wealthy, and he wants peace between his sons. Isaac believes his blessings are important because he wants God to help his sons. Jacob believes his estate and his blessings are important because he has a history of cheating and being cheated, and he does not want to leave anything to chance. And Joseph believes God’s master plan for the whole clan of Israel is the most important thing, so he only wants the clan to remember to bury him in Canaan.

I suspect that when I am close to death, I will believe the most important thing is to let the remaining members of my family know that I loved them. It might not make much practical difference, but I remember the reports of all those phone calls when the Twin Towers fell in New York City, and those who were about to die spent their last minutes saying “I love you”. When no inheritance is at stake, and God does not interact directly in the world, we have only our personal words of blessing to leave.

- The Torah says people’s souls go down to Sheol when their bodies die, but does not imagine any life for those souls, only a sort of endless cold storage.

- Ben (בֶּן) = son of. Bat (בַּת) = daughter of.

- Genesis 22:1-19. See my post: Vayeira: On Speaking Terms.

- Genesis 25:12-18 describes Abraham’s purchase of the cave of Machpeilah near Mamrei, where Sarah died.

- Genesis 25:21.

- Genesis 27:28 and 28:4.

- Genesis 33:18-19 and 33:25-30.

- See my post: Vayechi & 1 Kings: Deathbed Prophecies.

- Genesis 48:13-20. The blessing “May God make you like Efrayim and Menasheh” is still in use among Jews.

- See my posts: Vayechi: First Versus Favorite, and Vayechi: Three Tribes Repudiated.

- Genesis 47:29-31 and 49:29-30.

- Genesis 45:5-8 and 50:18-20.