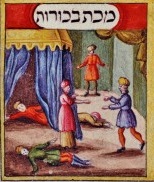

Ten “plagues”, or devastating miracles, destroy the land of Egypt bit by bit in the book of Exodus, until the pharaoh finally acknowledges the God character’s superior power and gives the Israelites unconditional permission to leave. Last week’s Torah portion, Va-eira (Exodus 6:2-9:35), ends with the seventh plague: hail. (See my post: Va-eira: Hail That Failed.)

The eighth plague, locusts,1 opens this week’s Torah portion, Bo (Exodus 10:1-13:16). First Moses and Aaron tell Pharaoh:

“Thus says Y-H-V-H, the god of the Hebrews: How long do you refuse to humble yourself before me? Release my people so they will serve me! Because if you refuse to release my people, here I am, bringing arbeh in your territory tomorrow!” (Exodus/Shemot 10:3-4)

arbeh (אַרְבֶּה) = locust swarm(s); the desert locust Schistocera gregaria.

Then they deliver a practical threat and two frightening images. The practical threat is that the plague of locusts will devour every green thing in Egypt left after the hail, leaving the human population without food.2

Before and after the practical threat, Moses and Aaron transmit God’s frightening images.

Eyes, up and down

The first image conjures blindness, like the plague of darkness that will follow the locust plague.

“And it [the locust swarm] will conceal the ayin of the land, and nobody will be able to see the land …” (Exodus 10:5)

ayin (עַיִן) = eye; view; spring or fountain.

After Pharaoh refuses to let the Israelites leave, the locust plague does exactly that.

And it concealed the ayin of the whole land, and it darkened the land and ate up all the green plants of the land and all the produce of the trees that the hail had left. Then nothing remained, nothing green remained on the trees or in the plants of the field, in the whole land of Egypt. (Exodus 10:15)

What does the word ayin mean in this story? The Hebrew Bible frequently uses ayin (most often in its duplex form, eynayim, עֵינַיִם = pair of eyes) to mean “view” or “sight”. Therefore many classic commentators assumed the Torah meant that the view of the land was blocked by the hordes of locusts. After all, the first reference to “the ayin of the land” is immediately followed by “nobody will be able to see the land”. If the locust swarms blanket every surface when they land, it would be as impossible to see through them as it is to see through the total darkness the Egyptians experience in the ninth plague.

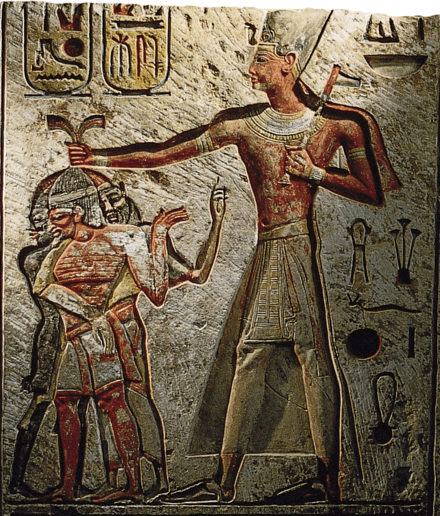

On the other hand, the phrase “the ayin of the land” occurs only three times in the Hebrew Bible: twice in this week’s Torah portion (see above), and once in Numbers 22:5 (see below). According to contemporary commentator Gary Rendsburg, the rarity of this phrase means it is probably an adaptation of a common Egyptian phrase, “the eye of Ra”, which referred to either the sun (since Ra was the sun god) or the land of Egypt (which belonged to Ra). He wrote that Onkelos, who translated the Hebrew Bible into Aramaic in the second century C.E., inserted the word for “sun” in both phrases: “… ‘the eye of the sun of the land’ in 10:5 and … ‘the eye of the sun of the whole land’ in 10:15.” Rendsburg suggested that Israelite readers would understand that the plague of locusts caused “the worst possible chain of events for the Egyptian nation, the disappearance of their omnipresent sun-god Ra”.3

Then what about the phrase “it darkened the land” in the second reference to “the ayin of the land”? When a locust swarm is in the air, it would not only block anyone underneath it from seeing the sun above, but also cast a broad shadow. According to Chizkuni,4 the shade cast by the swarm darkens the earth below.

However, the context of the only other biblical appearance of the phrase “the ayin of the land” refers to a swarm or horde on the ground. In the book of Numbers/Bemidbar. Balak, the king of Moab, is alarmed because Moses has led a horde of Israelites north from Egypt, and they are encamped on the border of his country. This king says to his advisors:

“Now the throng will lick bare everything around us like an ox licks bare the grass of the field!” (Numbers 22:4)

This is the behavior of locusts on the ground eating up the vegetation, not of locusts on the wing blocking the sun. King Balak then sends a message to the prophet-sorcerer Bilam, saying:

“Here are people [who] left Egypt, and hey! They conceal the ayin of the land, and they are living next to me! So now please come and put a curse on this people, because they are too strong for me …” (Numbers 22:5-6)

In other words, Balak sees the Israelites covering the ground like a giant swarm of locusts; and like locusts they are powerful because of sheer numbers.

Swarms: inside and out

After the practical warning that the coming locust swarms will consume Egypt’s entire food supply, Moses and Aaron transmit a second frightening image to Pharaoh—one that conjures an gruesomely intimate invasion.

“And they will fill your houses, and the houses of all your courtiers, and the houses of all Egyptians …” (Exodus 10:6)

It is not the first such invasion in the contest between the God character and Pharaoh. Before the second plague, frogs, God orders Moses to tell Pharaoh:

“And the Nile will swarm with frogs, and they will go up and come into your palace and your bedroom and climb into your bed, and go up into your courtiers’ houses and your people’s, and into your ovens and your kneading bowls.” (Exodus 7:28)

The fourth plague is arov, עָרֹב = swarms of insects (traditional translation), mixed vermin (translation based on the fact that the root ערב means “mixture”). Again God says:

“… and the arov will fill the houses of the Egyptians, and even the ground they stand on.” (Exodus 8:17)

Swarms of unpleasant animals are bad enough outside. Being unable to escape them even inside your own personal space is a horrifying invasion.

The plague of locusts both signals the coming plague of darkness, and echoes the earlier plagues of frogs and swarms of vermin. It also completes the destruction of Egypt, by eliminating the last sources of food. After Moses and Aaron warn Pharaoh about the locust plague,

Pharaoh’s courtiers said to him: “How long will this one be a snare for us? Release the men so they will serve Y-H-V-H, their god! Don’t you know yet that Egypt is lost?” (Exodus 10:7)

Pharaoh is so invested in his power struggle with God and Moses that he is past the point of caring whether his country is lost. But his courtiers have a different motivation. The first seven plagues have already ensured the economic downfall of Egypt; the loss of more crops will only mean that landowners lose more wealth as they feed their people during the coming famine. They have nothing to prove about who has more power. Some of Pharaoh’s courtiers have already acknowledged God’s power by bringing in their field slaves and livestock before the seventh plague, hail.5

So why do Pharaoh’s courtiers beg him to let the Israelites go? Probably because they cannot bear the thought of one more plague, especially a plague that will blot out their sight of the sun and the ground, and will once again invade even their bedrooms.

Over the past twenty years I have had problems I could deal with, and two persistent troubles that drove me crazy because I felt constantly under attack from well-meaning people who could not understand me and would not leave me alone. I was plagued by their incessant arguments and their refusals to accommodate me. These plagues darkened my life so I despaired of seeing sunlight. They invaded my home because I had to keep returning their phone calls. All I wanted was to be free of them.

I cut myself loose from one plague by resigning from my position. At the time, it seemed as hard for me to give up on that part of my life as it was for Pharaoh to give up and let the Israelites go. I waited out the other plague until my unwitting tormenter died. In that case, I was more like Pharaoh’s courtiers, whose power was limited.

Now that I am free, I hope that if I see another plague coming, I will be able to cut my losses right away. But I also pray that I will have empathy for others who suffer from unrelenting troubles. It is painfully hard to make a major change to improve your life, especially when you can see no illumination, and you have no safe place of refuge.

- When a wind brings multiple swarms of desert locusts into the same large region, it is still called a “plague” of locusts. (World Meteorological Organization, “Weather and Desert Locusts”, https://library.wmo.int/doc_num.php?explnum_id=3213#:~:text)

- Exodus 10:5.

- Gary Rendsburg, “YHWH’s War Against the Egyptian Sun-God Ra”, https://www.thetorah.com/article/yhwhs-war-against-the-egyptian-sun-god-ra.

- Chizkuni is a compilation of Torah commentary and insights written by 13th-century Rabbi Hezekiah ben Manoah.

- Exodus 9:13-26. See my post: Va-eira: Hail That Failed.