Every week of the year has its own Torah portion (a reading from the first five books of the Bible) and its own haftarah (an accompanying reading from the books of the prophets). This week the Torah portion is Pekudei (Exodus 35:1-40:38). The haftarah in the Sefardi tradition is 1 Kings 7:40-50; the haftarah in the Ashkenazi tradition is 1 Kings 7:51-8:21.

More, bigger, better.

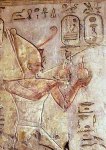

The tent-sanctuary and its courtyard, which Moses assembles at the end of the book of Exodus in this week’s Torah portion, Pekudei, are small and easily disassembled and reassembled. This is a necessity, since the Israelites must continue their journey to Canaan, erecting the sanctuary again every time they pitch camp.

But the first Israelite temple1 in Jerusalem and its courtyards, which King Solomon completes in this week’s haftarah, is a permanent structure. And it must be considerably larger, with more appurtenances, to accommodate not only a larger crowd of worshipers, but a larger number of priests and assisting Levites.

Sanctuary

People from Noah to Moses build altars to burn sacrifices for the God of Israel. But at the end of the book of Exodus, Moses assembles the first sanctuary or shrine: a structure with a roof, walls, and an entrance. This sanctuary is a small tent: 10 by 30 cubits (about 15 by 45 feet or 4½ by 13½ meters).2

The tent sanctuary needs to be small because it has to be disassembled and reassembled every time the Israelites travel to a new campsite . But there is enough room inside for the only people who are allowed to enter: Moses, the high priest Aaron, and Aaron’s sons.

The temple King Solomon builds in Jerusalem, described in both options for this week’s haftarah, is a tall building of stone and cedar, its footprint is 20 by 60 cubits (about 30 by 90 feet or 9 by 27 meters).3 Solomon’s temple is four times as big as Moses’ tent sanctuary—and it needs to be. As the main temple in the capital of a nation-state, it must accommodate many priests and their Levite assistants.

Holy of Holies

Both Moses’ sanctuary and Solomon’s temple are divided into two rooms: a main hall and a smaller chamber in back for the holy of holies. King Solomon adds a front porch with two gigantic bronze columns.

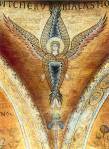

The “Holy of Holies” the innermost chamber in both the tent and the temple, contains only the ark of the covenant and two golden cherubs/keruvim, hybrid beasts with wings. (See my post Terumah: Cherubs are Not for Valentine’s Day.)

In the Tent of Meeting, the keruvim are part of the lid of the ark, one hammered out of the solid gold at each end. Their wings tilt toward each other, enclosing an empty space above the lid, a space from which God sometimes speaks. (See my post Pekudei & 1 Kings: A Throne for the Divine.)

Since the ark is only about four feet long, a keruv wing cannot be more than two feet long. But in Solomon’s temple, each keruv is about fifteen feet tall and has a fifteen-foot wingspan.4 An earlier passage in the first book of Kings describes how they are carved out of olive wood and overlaid with gold, then set up in the back chamber so that each one touches a wall with one wingtip and the tip of the other keruv’s wing with the other. Since the ark is smaller than these statues, it fits underneath them.

The priests brought in the ark of the covenant of God to its place, to the inner chamber of the bayit, to the holy of holies, to underneath the wings of the keruvim. (1 Kings 8:6)

It is not clear whether the inner chamber of the temple now contains four keruvim—the small pair on the ark and the large pair standing on the floor—or just the two large ones. But either way, the principle of “more, bigger, better” applies.

Main room of sanctuary

The main room of Moses’ sanctuary contains only three sacred ritual objects: a gold incense altar, a gold-plated table for display bread, and a solid gold lampstand with seven oil lamps.

The main hall of Solomon’s temple has the same three items, also gold—but the lampstands and perhaps the tables have multiplied.

When Moses assembles everything in this week’s Torah portion,

…he put the lampstand in the Ohel Mo-eid opposite the table, on the south side of the sanctuary. And he lit up the lamps before God, as God had commanded Moses. (Exodus 40:24-25)

Instead of placing one lampstand on the right side of the main hall, King Solomon’s crew positions five lampstands on each side.

And Solomon made all the vessels that were in the House of God, the gold altar and the gold table on which was the display bread and the pure gold lampstands, five on the right side and five on the left side in front of the inner chamber, and the gold blossom [decorations] and lamps and wick cutters … (1 Kings 7:48-49)

In the first book of Kings, Solomon’s temple contains only one bread table.

And Solomon made all the equipment that was in the bayit of God: the gold altar and the gold table that had the display bread upon it… (1 Kings 7:48)

But by the fourth century B.C.E., when the two books of Chronicles were written, the bread table had multiplied.

And he made ten tables and he set them in the main hall, five on the right side and five on the left side; and he made a hundred gold sprinkling-basins. (2 Chronicles 4:8)

After all, if one table is good, ten tables must be better.

Wash basins in courtyard

Like most religions in the ancient Near East, the religion outlined in the Hebrew Bible makes a distinction between public worship and the rituals conducted by priests. The public place of worship is the open courtyard in front of the sanctuary, where animals and grain products are offered at the altar. Only priests are allowed to go inside the tent or temple.

When priests move from serving at the altar to serving inside the tent or building, they stop to wash their hands and feet. So when Moses is setting up the portable sanctuary for the first time,

… he put the basin between the Ohel Mo-eid and the altar, and he place there water for washing. And from it Moses and Aaron and his sons washed their hands and their feet. When they came into the Ohel Mo-eid and when they approached the altar they washed, as God had commanded Moses. (Exodus 40:30-32)

Ohel Mo-eid (אֹהֶל מוֹעֵד) = Tent of Meeting. (From ohel (אֹהֶל) = tent and mo-eid (מוֹעֵד) = meeting, meeting place, appointed time or place.)

The courtyard in front of Solomon’s much bigger temple has a huge bronze “sea” resting on twelve bronze oxen. (See last week’s post, Haftarah for Vayakheil: Symbolic Impressions.) In addition to this much more impressive basin, Solomon’s master artisan makes ten smaller bronze basins on elaborate wheeled stands covered with engraved spirals, cherubim/keruvim, lions, and palm trees.

And he placed five stands at the entrance of the bayit on right and five at the entrance of the bayit on the left… (1 Kings 7:39)

bayit (בָּיִת) = house, important building, household.

Why settle for one small basin when you could have a giant “sea” along with ten basins?

When the temple is complete with all its furnishings, King Solomon proudly declares:

I certainly built an exalted bayit for You, an abode for you to rest in forever! (1 Kings 8:13)

When it comes to religious ritual objects, is more or bigger really better?

Anything made of precious metals would have provided a locus for worship that met the expectations of the Israelites Moses led through the wilderness. In Exodus, thanks to the tent sanctuary and its ritual objects, they no longer feel the need for a golden calf. And if the ritual objects were too large or too many, they would be too hard to transport through the wilderness.

The capital of a new nation-state, however, needs not only a large and permanent temple, but also a large and glittering display to impress both foreign visitors and the nation’s citizens with the power of its religion. So in front of King Solomon’s temple are gigantic bronze columns, the oversized bronze “sea” on twelve bronze oxen, ten bronze lavers on elaborate stands, and a host of priests walking in and out of the building. Inside, there are enough lampstands and tables to accommodate those priests as they perform the rituals, which would help reconcile them to a centralized religion.

In my own life, I have responded to religious cues on both scales, small and large. I know the calm, centering effect of lighting two candles for Shabbat, and the hushed tenderness of reading from a Torah scroll in an otherwise unremarkable room. I also know the awe I feel when I stand at the ocean, in a forest of tall trees, or in a medieval cathedral (even though as a Jew, I am a foreign visitor there).

I do not want to lose either the personal connection of rituals with small sacred things, or the impersonal awe of encounters with vastness. Both a tent and a temple are exalted places where God might rest.

- The Jebusites who occupied Jerusalem before King David conquered part of it probably had their own shrine. Genesis 14:17-20 mentions a Jebusite priest-king named Malki-tzedek who blesses Abraham.

- Exodus 26:1-6.

- 1 Kings 6:2.

- 1 Kings 6:23-26.