Who will meet in the “Tent of Meeting”?

Moses receives instructions for making a portable tent-sanctuary for God in last week’s portion, Terumah. This week’s portion, Tetzaveh (“you shall command”), is the first one to call the sanctuary the ohel mo-eid, the “Tent of Meeting”—an expression that appears 137 times in the books of Exodus through Deuteronomy.

This week’s portion is also the first to reveal who will meet at or inside the tent. But in its first appearance, the phrase “Tent of Meeting” is merely a location. God tells Moses:

And you, you shall command the children of Israel, so they will take for you pure oil of beaten olives for the light, to make the lamp go up regularly. In the ohel mo-eid, outside the dividing curtain that is in front of the testimony [in the ark], Aaron and his sons shall set it up from evening until morning before God. [This is] a decree forever for the generations from the children of Israel. (Exodus/Shemot 27:20-21)

And you, you shall command the children of Israel, so they will take for you pure oil of beaten olives for the light, to make the lamp go up regularly. In the ohel mo-eid, outside the dividing curtain that is in front of the testimony [in the ark], Aaron and his sons shall set it up from evening until morning before God. [This is] a decree forever for the generations from the children of Israel. (Exodus/Shemot 27:20-21)

ohel (אֹהֶל) = tent.

mo-eid (מוֹעֵד) = appointed place for meeting with God; appointed time (usually for a religious festival). (From the root ya-ad, יָעַד = appoint a time or place.)

ohel mo-eid (אֹהֶל מוֹעֵד) = Tent of Meeting (i.e. the tent appointed for meeting with God).

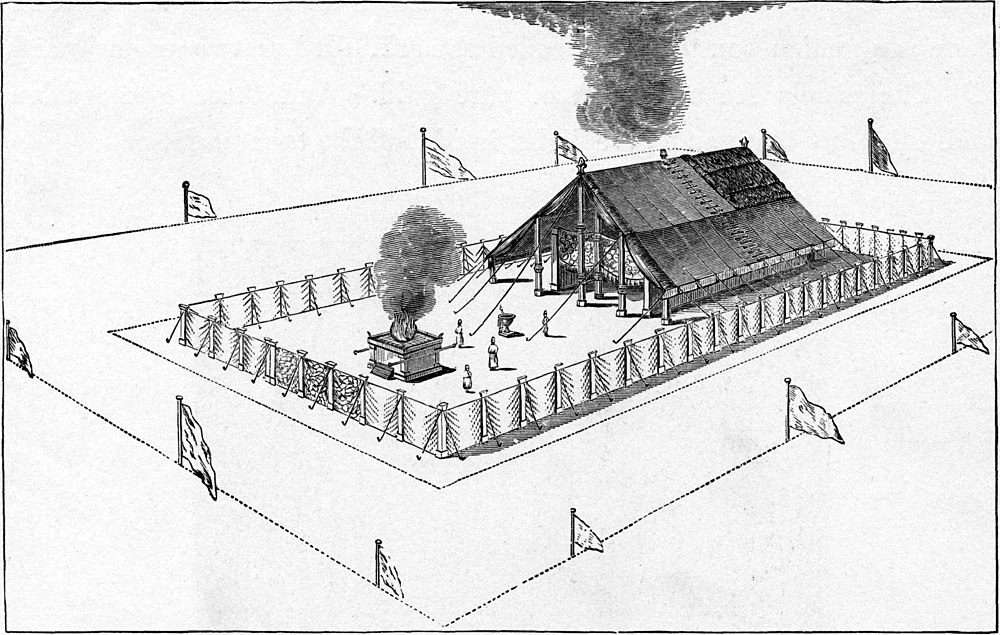

The ohel mo-eid is the portable tent-sanctuary God described to Moses in last week’s Torah portion, a two-chamber tent with a dividing curtain screening off the Holy of Holies from the larger front chamber.1 The menorah whose lamps the priests must fill is inside the tent’s front chamber.

The portion Tetzaveh then describes the vestments to be made for the new priests, followed by the ritual for ordaining them. First Moses must assemble Aaron and his four sons, a bull and two rams, three kinds of bread, and the new priestly garments.

Then you shall bring Aaron and his sons to the entrance of the ohel mo-eid and you shall wash them in water. (Exodus 29:4)

Both the basin for the priests’ ritual washing and the altar for burnt offerings are located outside the Tent of Meeting, in front of the entrance.

And you shall bring the bull to the front of the ohel mo-eid, and Aaron and his sons shall lean their hands on the head of the bull. And you shall slaughter the bull before God, at the entrance of the ohel mo-eid. (Exodus 29:10-11)

And you shall bring the bull to the front of the ohel mo-eid, and Aaron and his sons shall lean their hands on the head of the bull. And you shall slaughter the bull before God, at the entrance of the ohel mo-eid. (Exodus 29:10-11)

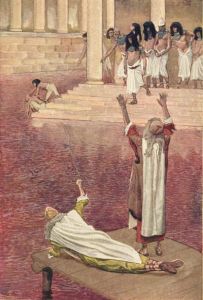

After washing and dressing Aaron and his sons, Moses must make the first offerings on the new altar, and sprinkle some of the blood on both the altar and the five men.2 After Moses has made all the offerings, the remaining bread and the remaining meat from the second ram go to the men being ordained.

And Aaron and his sons shall eat the flesh of the ram, and the bread that is in the basket, at the entrance of the ohel mo-eid. (Exodus 29:32)

The whole process, from washing to eating, must be carried out in front of the Tent of Meeting, and must be repeated every day for a total of seven days in order to sanctify both the priests and the altar. After that, the priests will make daily offerings, which are briefly listed. With the last one, an evening offering of a lamb, God finally mentions why the portable sanctuary is called the “Tent of Meeting”.

[It is] a perpetual rising-offering3 for your generations at the entrance of the ohel mo-eid, in front of God, where iva-eid with you, to speak to you there. (Exodus 29:42)

iva-eid (אִוָּעֵד) = I shall meet, I shall arrange meeting(s). (Also from the root ya-ad.)

The “you” in this sentence is plural. The next sentence declares that the ohel mo-eid will be the locus or focus where all the Israelites can meet God.

Veno-adeti there for the Children of Israel, and it will be sanctified by my glory. (Exodus 29:43)

veno-adeti (וְנֹעַדְתִּי) = And I will arrange meeting(s). (Also from the root ya-ad.)

The Torah does not explain what kind of meeting or meetings will occur between God and the Israelites. But God does say:

And I will dwell in the midst of the Children of Israel and I will be their god. (Exodus 29:45)

Maybe the Israelites have a meeting with God whenever they see the pillar of cloud and fire that rests over the Tent of Meeting when they are encamped.4 Or when they brings offerings to the courtyard in front of the tent and watch while the priests perform the ritual actions to send them up to God. Or maybe living so close to the Tent of Meeting is enough for the Israelites to meet God.

The Torah portion then describes the incense altar, and God adds:

And you shall place it in front of the dividing curtain that is in front of the Ark of the Testimony, in front of the atonement-cover that is over the testimony, where iva-eid with you. (Exodus 30:6)

This time “you” is singular. Only Moses, to whom God is speaking, will meet with God inside the back chamber of the tent, the Holy of Holies, in front of the atonement-cover on the ark.

Thus the innermost chamber the Tent of Meeting is the appointed place where Moses and God meet, while the tent as a whole is the focus for meetings between rest of the people and the God who dwells in their midst.

*

Before there is a Tent of Meeting, people in the Torah never know where God might speak to them. God’s voice might come in a dream, or from a stranger who turns out to be not human after all, or from a burning bush. But in this week’s Torah portion Moses learns that God has designated the Tent of Meeting as the appointed place. God still speaks to Moses at odd moments, but a formal meeting takes place inside or in front of the tent.

When the Israelites have finished making all the items for the Tent of Meeting and Moses assembles it for the first time, God fills the tent with the divine manifestations of cloud and glory (or impressiveness).

And Moses was not able to enter the ohel mo-eid because the cloud rested upon it and the glory of God filled the sanctuary. (Exodus 40:35)

The presence of God is too strong for the meeting to take place! So the book of Leviticus/Vayikra begins with God summoning Moses and speaking to him from the Tent of Meeting, as if God has changed the divine frequency in order to meet the appointment with Moses.

*

Many people today believe they have an appointed place to meet with God: their synagogue or church or mosque or temple. Some religions still claim that God gives direct instructions to their leaders. And all too many people believe that the “real” God can only be found in their religion’s sacred places.

I pray that someday people will notice the glory of God outside their own exclusive Tent of Meeting, and the divine will dwell in the midst of everyone on earth.

—

- Exodus 26:31-33.

- See my posts Tzav: Oil and Blood and Tzav: Horns, Ears, Thumbs, and Toes.

- olah (עֹלָה) = rising-offering. (From the root alah (עלה) = go up.) In an olah the entire slaughtered animal is burned up into smoke, which rises to the heavens.

- Exodus 40:36-38, Numbers 9:15-17.