What does it take to create something that will help people feel the presence of God?

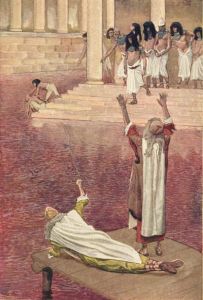

Aaron tries to do this when he makes the Golden Calf in last week’s Torah portion, Ki Tissa. At first, the people are ecstatic over the idol, bowing down to it and singing and dancing. But this simple and undisciplined religious outlet does not last. When Moses returns and grinds the calf into gold dust, nobody protests. Moses stirs the gold dust into water, and they all meekly swallow it. Aaron’s creation turns out to be a failure.

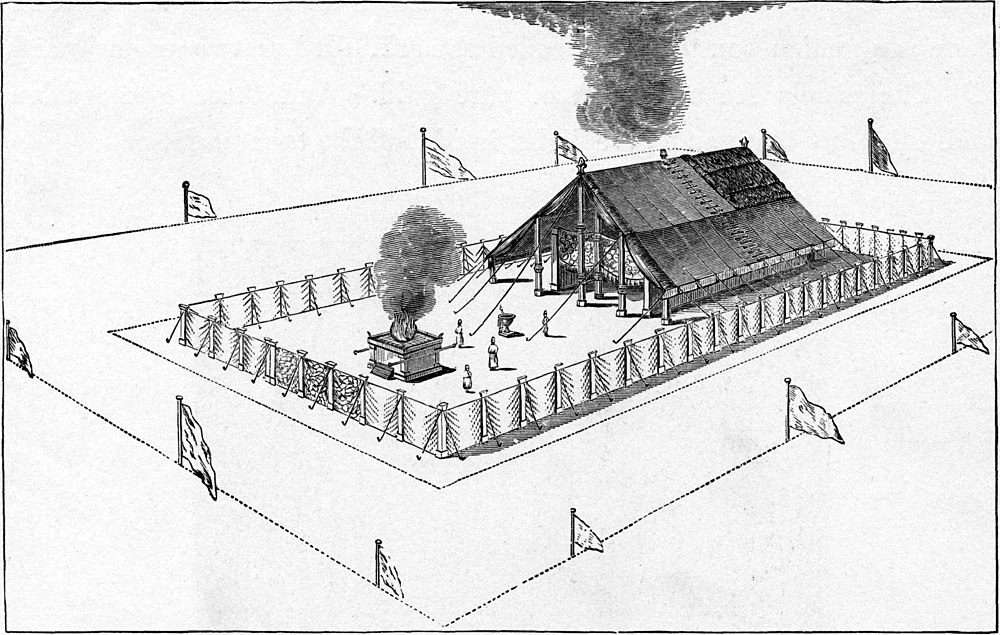

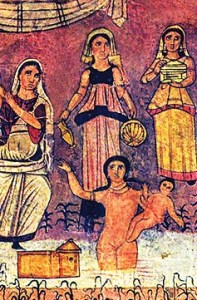

In this week’s Torah portion, Vayakheil (“And he assembled”), the master craftsman Betzaleil begins making the holy objects for the new sanctuary. The completed creation is so successful that it sustains the religion of the Israelites for several centuries, until King Solomon replaces it with the temple in Jerusalem.

The key difference between Aaron and Betzaleil as creators of religious objects appears in the Torah twice, repeated word for word. In the portion Ki Tissa, God says it to Moses. In this week’s portion, Moses says it to the Israelites:

See? God has called by name Betzaleil, son of Uri, son of Chur, of the tribe of Yehudah. And [God] has filled him with ruach of God, with chokhmah, with tevunah, and with da-at, and with every craft. (Exodus/Shemot 35:30-31)

ruach (רוּחַ) = wind; spirit, motivation, overwhelming state of mind.

(Usually when the ruach of God comes over someone in the Hebrew Bible, that person speaks as a prophet or leads people into battle. Exceptions are Samson, who is gripped by a murderous rage and supernatural strength; and Betzaleil the artist, who is filled with a divine motivation to create.)

chokhmah (חָכְמָה) = wisdom; inspiration.

tevunah (תְבוּנָה) = insight, rational understanding, analytic ability.

da-at (דַעַת) = knowledge.

In later Kabbalistic writings, chokhmah and binah (another form of the word tevunah) are two of the sefirot or divine powers. Chokhmah is the sefirah associated with the left side of the head, i.e. the left brain that popular science now associates with non-rational, intuitive, holistic consciousness. Binah (tevunah) is the sefirah associated with the right side of the head, i.e. the right brain that we now associate with rational, logical, analytic thinking. In the Kabbalist system, da-at is the product of chokhmah combined with binah.

Aaron, although he will serve as the high priest, lacks the four qualities with which God fills Betzaleil. When the Israelites are waiting at the foot of Mount Sinai in Ki Tissa, Aaron feels no ruach of God, no divine urge to create a holy object. The people decide Moses will never return and order Aaron: Get up, make for us gods that will go before us! (Exodus 32:1). Then Aaron acts, but only to satisfy the crowd.

He has no chokhmah, no inspiration nor wisdom about what to make; he merely calls for gold earrings to melt down, since the finest idols are made of gold.

He took it from their hands and he shaped it with the engraving tool, and he made it into an image of a calf. (Exodus 32:4)

Afterward, when Aaron explains to Moses what happened, he says: I said to them, “Who has gold? Pull it off yourselves.” And they gave it to me and I threw it into the fire and out came this calf.” (Exodus 32:24)

Aaron admits that he acted without any of the insight or discrimination of tevunah, and also without any da-at, any knowledge of what would emerge from the fire.

Betzaleil, on the other hand, is born betzalmeinu—in God’s shadow or image—when it comes to creativity. (See my earlier post, Vayakheil: Shadow Power.) **** He creates under the protection of God’s shadow. God “fills” him with the qualities he already has the potential and experience to develop.

Even as Moses comes down with God’s basic design for a portable sanctuary, Betzaleil is filled with a divine desire to create it. He has the chokhmah to visualize the whole thing, and to imagine beautiful and inspiring objects—from the gold keruvim (hybrid winged beasts) on top of the ark to the design embroidered in brilliant colors on the curtain at the entrance to the Tent of Meeting. He has the tevunah to analyze and understand how each part can be made well and assembled into the whole. And he has da-at, knowledge, of every craft: metal-working, jewelry, wood-working, weaving, and embroidery.

Betzaleil is so filled with chokhmah, tevunah, and da-at that he and his assistant can teach other craftsmen and craftswomen among the people.

And [God] put teaching into his heart, him and Ahaliyav son of Achisamakh of the tribe of Dan. (Exodus 35:34)

And Betzaleil and Ahaliyav and everyone wise of heart to whom God gave chokhmah and tevunah for da-at and for doing all the work for the service of the Holy, they shall do everything that God commanded. (Exodus 36:1)

The sanctuary that is completed in next week’s Torah portion, Pekudei, is the product of the grand design Moses heard from God; the divine spirit, inspiration, understanding, and know-how of the master artist, Betaleil; and the enthusiasm and wisdom of the contributors in the community. No wonder it becomes a place where people feel God’s presence.

I think that the qualities God gives Betzaleil are necessary for anyone to produce truly moving art, whether its explicit goal is religious or not. I know that when I do “creative writing”, especially of Torah monologues and fiction, both my motivation (ruach) and my inspiration (chokhmah) seem to come from a mysterious place outside myself, or perhaps from some inner place so deep my conscious mind can never penetrate it. I might as well say they come from God, the great mystery.

But the most burning motivation and inspiration leads nowhere without the application of rational insight and analysis (tevunah). My own ability in this area is a talent I was born with, a gift of God, that I have developed over many years of practice. And as in Kabbalah, I have found that the combination of left-brained inspiration (chokhmah) and right-brained analysis (binah or tevunah) does indeed result in knowledge (da-at).

The final requirement for creating art is to actually do all the labor. I am grateful that the ruach that blows through me from the unknown source I call God is strong enough to motivate me to keep on working, with enthusiasm—like the Israelites in this week’s Torah portion.

May the divine spirit be strong in all artists.