Every week of the year has its own Torah portion, a reading from the first five books of the Bible, and its own haftarah, an accompanying reading from the books of the prophets. This week the Torah portion is Yitro (Exodus 18:1-20:23) and the haftarah is Isaiah 6:1-13 in the Sefardic tradition (Isaiah 6:1-7:6 plus 9:5-6 in the Ashkenazic tradition).

I have met a few mystics who savor every numinous experience, and spend their lives trying to get more of them. I have not met any prophets, as far as I know. But since I am a Jew who loves research and analysis, I study the Hebrew Bible, including its many stories of prophets who see visions, hear God, and spend their lives passing on God’s words.

The biblical individual who is most reluctant about becoming a prophet is Moshe (“Moses”), who argues with God at the burning bush before finally succumbing and accepting his vocation.1 In this week’s Torah portion, Yitro, Moshe has returned to Mount Sinai as the leader of a horde of Israelites from Egypt, and God gives them all a frightening experience of the transcendent. (See my post Yitro & Bereishit: Don’t Even Touch It.) It does not turn anyone else into a prophet.

Most of the biblical prophets after Moses simply hear from God and do what they are told;2 we never find out how their vocation began. The exceptions are Shmuel (“Samuel”), who hears a voice as a boy when he is sleeping near the sanctuary;3 Elisha, who is chosen by another prophet, and runs after him;4 Yermiyahu (“Jeremiah”), who hears God tell him that he was born to be a prophet;5 and Yeshayahu (“Isaiah” in English) in this week’s haftarah.

Starting with a vision

The first 39 chapters of the book of Isaiah, commonly called “First Isaiah”, record the prophecies of an 8th-century citizen of the kingdom of Judah, possibly a priest, named Yeshayahu son of Amotz. (The remaining 27 chapters in the book, commonly called “Second Isaiah”, were added two or three centuries later and feature an unnamed prophet.)

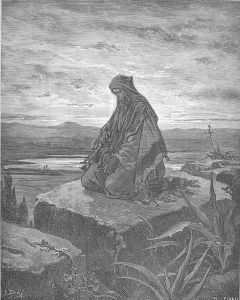

In the sixth chapter of the book of Isaiah, and Yeshayahu (Isaiah) tells the story of his call to prophecy.

In the year of the death of the king Uziayahu, 6 I saw my Lord sitting on a high and lofty throne. And the skirts of [God’s] robe filled the heykhal. (Isaiah 6:1)

heykhal (הֵיכָל) = temple, palace.

What is the setting for this vision? The commentary is divided on whether Yeshayahu (Isaiah) is standing inside the temple in Jerusalem, or seeing a divine palace in the heavens.

Alter wrote: “Since it was believed that there was a correspondence between the Temple in Jerusalem and God’s celestial palace, it is understandable that Isaiah should have a vision of God enthroned in the Temple. God apparently is imagined as having gigantic proportions …”7

If Yeshayahu (Isaiah) were indeed a priest standing in the main room of the temple, he would see real clouds of incense filling the hall before he beholds God seated on a throne.

On the other hand, Canaanite religions told of various gods coming to a supreme god’s palace in the sky to decide the fate of human beings. The Israelite religion evolved to reject other gods, but the idea of a palace in the sky persisted.8

Or the vision might combine both settings. Rashi wrote: “I saw Him sitting on His throne in heaven with His feet in the Temple, His footstool in the Sanctuary …”9

Yeshayahu (Isaiah) sees not only the figure of a seated man wearing a robe that overflows to fill the room, but also supernatural attendants serving him.

Serafim were standing above, each with six wings; with one pair he covered his face, and with a pair he covered his feet, and with a pair he was flying. And this one called to that one, and said: “Holy! Holy! Holy! The glory of the God of tzevaot fills the earth!” (Isaiah 6:2-3)

serafim (שְׂרָפִים) = burning creatures—either poisonous snakes or fiery angelic beings. (From the root verb saraf, שָׂרַף = burn.)

tzevaot (צְבָאוֹת) = armies. (Singular: tzeva, צְבָא. See my post Haftarat Bo—Jeremiah: The Ruler of All Armies.)

The term “God of Armies” often refers to armies on earth, but in some contexts God is the master of metaphorical “armies” of stars—or perhaps serafim—in the sky. In the first book of Kings, a prophet named Mikhayahu son of Yimlah introduces a prophecy by announcing:

“Thus I heard the word of God: I saw God sitting on [God’s] throne, and all the tzeva of the heavens were standing above, to [God’s] right and to [God’s] left.” (1 Kings 22:19)

According to Kugel, the description of serafim in the book of Isaih affirms that the stars and planets are not other gods, but “actually seraphim, ‘burners,’ who lit up the sky but whose principal function was to praise God, calling out, ‘Holy, holy, holy’ to the Creator.”10

And the doorposts shook from the sound of the calling, and the house was filling with smoke. And I said: “Alas for me, because I am undone! For I am a man of impure lips, and I live among a people of impure lips. Yet my eyes have seen the King, the God of tzevaot!” (Isaiah 6:4-5)

Yesheyahu (Isaiah) believes he is unworthy of a vision of God. And he identifies his lips as the source of impurity.

Kugel pointed out that “there is no such concept as ‘impure lips’ in biblical law.”11 Ritual impurity comes from contact with corpses, genital discharges, and skin disease. Other commentators have noted that in the book of Exodus, Moshe objects to being a prophet on the grounds that he has uncircumcized lips.12 But Moshe means that he is a poor speaker, not that his lips are contaminated.

Apparently Yesheyahu (Isaiah) is thinking along the same lines as the prophet in the later book of Zephaniah, who connects purity of lips, i.e. language, with not lying or speaking deceitfully.13

At any rate, Yesheyahu’s focus on his lips indicates that he already believes, or hopes, that God wants him to be a prophet. How could he speak for God when he has “impure lips”, like all the other Israelites?

Then one of the serafim flew over to me, and in his hand was a live coal; with tongs he had taken it from on top of the altar. And he touched it to my lips, and said: “Behold, this touch on your lips removes your iniquity and atones for your guilt.” (Isaiah 6:6-7)

Volunteering

Then I heard the voice of my Lord saying: “Whom will I send? And who will go for us?” And I said: “Here I am. Send me!” (Isaiah 6:8)

This verse, like the one about the tzevaot of the heavens, echoes the vision that the prophet Mikhayahu describes to King Achav of Israel.

“And God asked: “Who will entice Achav, so he will go up, then fall at Ramot-Gilead?” And this one said thus, and that one said thus. Then a spirit went out and stood before God and said: “I will entice him.” (1 Kings 22:20-21)

This spirit plans to entice King Achav by putting lies into the mouths of all the human prophets, so that the king will march on Ramot-Gilead and be defeated.

In Yesheyahu’s (Isaiah’s) vision, God asks “Who will go for us?” without saying what the mission is. Yesheyahu, elated by his purification, enthusiastically volunteers.

A doomed job

And [God] said: “Go, and you must say to the people: Keep hearing, but you will not understand; and keep seeing, but you will not perceive!” (Isaiah 6:9)

This message seems designed to make people hate the messenger. Rashi explained that God is frustrated that the people of Judah are making no effort to understand what God wants from them.14 Plaut wrote: “The transgressors don’t want to be confronted with the truth, and when someone tries to tell it to them, they close their minds and become incapable of listening any further.”15

Then why does God want a prophet to speak at all? According to Steinsaltz, “… the people were warned so that they would recall the warning sometime later.”16

Next God informs Yeshayahu (Isaiah) that he must disguise the truth—the very behavior that made him believe his lips were impure.

“Make the mind of this people obtuse, and make its ears dull and its eyes blurred; lest it see with its eyes and hear with its ears and discern with its mind, and turn around [repent] and heal itself”. (Isaiah 6:10)

According to the Talmud, God is referring to the healing of forgiveness.17 And God does not want to forgive the people yet. Prophets in the Hebrew Bible (except for ecstatics; see my post Haftarat Ki Tissa: Ecstatic versus Rational Prophets) normally warn nations and kings about the bad things that will happen if they do not change their ways; the prophet and God hope that people will heed the warning and change. But in this case, God is determined to punish Judah, and does not want its population to repent and change too soon.

I wonder if Yeshayahu (Isaiah) would have volunteered so eagerly in his vision if he had known God’s plan.

On the other hand, Yeshayahu has already delivered prophecies for five chapters before he recounts what he saw and how he volunteered to be a prophet. Perhaps his failure to get anyone to change has made him conclude, bitterly, that God does not really want anyone to repent, so he tells the story of his vision accordingly.

Then I said: “How long, my Lord?” And [God] said: “Until towns are ruined and there are no inhabitants, and in houses there are no humans, and the ground is a ruined desolation. For God will send the humans far away, and [there will be] many forsaken places in the midst of the land.” (Isaiah 6:11-12)

Will Yesheyahu’s (Isaiah’s) deceptive prophecies result in the desolation of Judah? Or must Yesheyahu keep uttering ineffective prophecies until Judah is ruined and empty?

The idea of being sent far away would occur naturally to Yesheyahu (Isaiah), since while he was uttering prophecies in the southern kingdom of Judah, the Assyrian Empire was conquering the northern kingdom of Israel and forcibly relocating tens of thousands of its citizens.18

The vision closes with God saying:

“But while a tenth part is still in it [Judah], then it will turn back [repent]. And it will be ravaged like the terebinth and the oak, of which stumps are left when [they are] felled. Its stump is a holy seed.” (Isaiah 6:13)

Steinsaltz explained: “The people who will ultimately survive will be holy. They will have endured everything that was necessary, and they will not fall into decline again.”19

The northern kingdom of Israel never regenerated after so many of its citizens were deported by Assyria. In the 6th century B.C.E., the southern kingdom of Judah suffered from similar deportations by the conquering Babylonians. Some of those Judahites did return later to rebuild Jerusalem. So either Yesheyahu’s (Isaiah’s) vision concludes with a long-term prediction, or a later scribe added the last verse to this story.

The prophetic careers of both Moshe (Moses) and Yesheyahu (Isaiah) begin with a numinous experience in which God speaks to them. Both men object that their lips are not suitable for a job as God’s agent—Moshe because he cannot speak well, Yesheyahu because he has been speaking deceptively.

Moshe continues to argue with God, finally saying “Send someone else!” before he gives up and obeys God’s order to go back to Egypt.20 Then he grows in the job, argues with God on behalf of the Israelites, and succeeds in bringing the next generation to Canaan before he dies.

Yesheyahu (Isaiah) embraces his calling as soon as his lips are purified. He spends 38 years conscientiously announcing prophecies, then dies after telling King Chizkiyahu (“Hezekiah” in English) that Babylon will seize his country, his children, and the treasures in his palace.21 Despite all his prophecies, Yesheyahu never sees the fall of Judah, nor the rebuilding of Jerusalem.

Yet once someone in the Hebrew Bible starts speaking for God, he or she is not allowed to quit.22

Today, individuals are called prophets if they have unusually keen spiritual and moral insight and a way with words, and use these abilities to publicly call for change in a society. I wonder what moves them to embark on this difficult path in life. Are they overwhelmed by a vision? Are they volunteers? Are they driven by a feeling that they have no other choice?

- See my posts Shemot: Empathy,Fear, & Humility, Shemot: Names and Miracles, Shemot: Not a Man of Words, and Shemot: Moses Gives Up.

- Except for Jonah, who runs away, then reluctantly does his job after being swallowed and vomited out by a big fish.

- 1 Samuel 3:1-10.

- 1 Kings 10:19-21.

- See my post Haftarat Shemot or Matot—Jeremiah: A Congenital Prophet.

- King Uziyahu of Judah died sometime between 742 and 734 B.C.E.. Modern scholars believe the prophecies in First Isaiah were recited orally, and not written down until at least a century later.

- Robert Alter, The Hebrew Bible, Volume 2: Prophets, W.W. Norton & Co., New York, 2019, p. 640.

- E.g. Micah 1:2-3.

- Rashi (acronym of 11th-century Rabbi Shlomoh Yitzchaki), translation in www.sefaria.org.

- James L. Kugel, How to Read the Bible, Free Press, New York, 2007, p. 541.

- Ibid.

- Exodus 6:12.

- Zephaniah 3:9, 3:13.

- Rashi, ibid.

- W. Gunther Plaut, The Haftarah Commentary, translated by Chaim Stern, UAHC Press, New York, 1996, p.170.

- Rabbi Adin Even-Israel Steinsaltz, Introductions to Tanakh: Isaiah, in www.sefaria.org.

- Talmud Bavli, Megillah 17b.

- Yeshayahu’s prophecies began around 740 B.C.E., and were recorded around 640 B.C.E. The Assyrian deportations occurred in 734-732, 729-724, and 716-715 B.C.E.

- Steinsaltz, ibid.

- Exodus 4:13.

- Isaiah 39:5-7. This passage may also have been added by a later scribe.

- See the book of Jonah.