by Melissa Carpenter, Maggidah

Moabites and Midianites are two distinct peoples in most of the Bible. Yet they appear to be interchangeable in a story about sex and revenge that runs through three Torah portions in the book of Numbers/Bemidbar: the portions Balak (last week), Pinchas (this week), and Mattot (next week).

The conflation between Moabites and Midianites begins after the Israelites have marched through the wilderness east of Moab and then conquered two Amorite kingdoms to its north. The Israelites camp on the east bank of the Jordan River, in their first newly captured territory–which is now described as a former part of Moab.

And the Israelites journeyed [back], then encamped on the plains of Moab, across the Jordan from Jericho. (Numbers/Bemidbar 22:1)

Balak, the king of Moab, is afraid they will go south and attack his country next.

And [the king of] Mo-av said to the elders of Midyan: Now the congregation will nibble away all our surroundings, as an ox nibbles away the grass of the field. (Numbers 22:4)

Mo-av (מוֹאָב), Moab in English = a kingdom east of the Dead Sea; the people of this kingdom. (The actual etymology is unknown. Genesis/Bereishit 19:36-37 claims the Moabites are descended from incest between Lot and one of his daughters, and implies that the daughter named her son Mo-av to mean “from father”. The actual Hebrew for “from father” would be mei-av מֵאָב.) The Moabite language was a Hebrew dialect, and appears on a circa 840 B.C.E. stele about a war between Israel and a Moabite king named Mesha.

Midyan (מִדְיָן), Midian in English = a territory occupied by the people of Midian, whose geographic location differs in various parts of the Bible. (Possibly from the Hebrew dayan (דַּיָּן) = judge. Midyan might mean “from a judge”, “from judgement”, or “from a legal case”.) References to a people called Madyan or Madiam appear in later Greek and Arabic writings, and Ptolemy wrote of a region of Arabia called Modiana (see #1 on map), but archeology has not yet proven the existence of a country of Midian. The Midianites may have been a nomadic people without a fixed territory.

When King Balak sends a delegation to the prophet Bilam to ask him to curse the Israelites, it consists of “the elders of Moab and the elders of Midian“. (Numbers 22:7).

When Bilam arrives at the mountaintop overlooking the Israelite camp, King Balak is there with “all the nobles of Moab” (Numbers 23:6, 23:17) but apparently no Midianites.

After Bilam fails to curse the Israelites and goes home, a brief story in the portion Balak describes how some young women invite the Israelites to participate in ritual feasts to their gods, and many Israelites end up bowing down to the local god, Baal Peor. (See my post Balak: False Friends?) At first, these women are identified as Moabites.

And Israel settled among the acacias, and the people began to be unfaithful with the daughters of Moab. (Numbers 25:1)

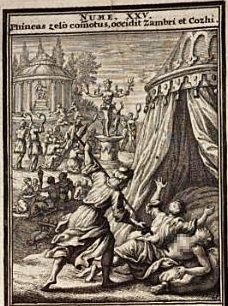

Next, an Israelite man brings a foreign woman into the Tent of Meeting itself for sex. Aaron’s grandson Pinchas saves the day by quickly spearing the two of them. The woman is identified as a Midianite, and in the next Torah portion, Pinchas, we find out she is a woman of rank.

And the name of the Midianite woman who was struck down was Kozbi, daughter of Tzur, the head of the people of a paternal household from Midian. And God spoke to Moses, saying: “Be hostile toward the Midianites, and strike them down. Because they were hostile to you through their deceit, when they deceived you about the matter of Peor…” (Numbers 25:15-18)

Suddenly the Moabite women who invited the Israelites to feasts for their gods are being called Midianites!

In the next Torah portion, Matot (“Tribes”), God reminds Moses to attack the Midianites, but does not mention the Moabites.

And they arrayed against Midian, as God had commanded Moses, and they killed every male. And the kings of Midian they killed …five kings of Midian, and Bilam son of Beor, they killed by the sword. But the children of Israel took captive the women of Midian and their little ones… (Numbers 31:7-9)

This story ends with the slaughter of the captive Midianite women. (See my post Mattot: Killing the Innocent.)

And Moses said to them: “You let every female live! Hey, they were the ones who, by the word of Bilam, led the Israelites to apostasy against God in the matter of Peor, so there was a plague in the assembly of God. So now, kill every male among the little ones and every woman who has known a man by lying with a male, kill!” (Numbers 31:15-17)

Here Moses declares that it was Midianite women who seduced Israelites into worshiping Baal Peor. The Moabite women are no longer mentioned.

When we look at the storyline over three Torah portions, the enemies of the Israelites seem to change from a coalition of Moabite and Midianite leaders, to Moabite men, to Moabite women, to Midianite women, to Midianites in general. How can we explain the shift from Moabites to Midianites?

As usual when it comes to inconsistencies in the scripture, the commentary falls into three camps: the apologists, the scientists, and the psychologists. (A fourth camp of commentary is the mystics, who focus on individual phrases and words, and ignore inconsistencies in storylines.)

The Apologists

The apologists take the Torah as literal history, and find clever ways to explain apparent inconsistencies.

The Talmud considers Midian and Moab two separate nations that became allies against the Israelites. Thus men from both nations hire Bilam to curse the Israelites, and make their daughters seduce the Israelite men (in order to cause the God of Israel to abandon the Israelites and leave them vulnerable).

In one Talmud story, God tells Moses to spare Moab and attack only Midian because God wants to preserve the land of Moab for the birth of Ruth, the virtuous ancestor of King David. (Talmud Bavli, Bava Kama 38a-b.) Another tractate of the Talmud (Sotah 43a) says that the attack on Midian is actually vengeance for the episode in the book of Genesis when a band of Midianites buys Joseph from his brothers and sells him into slavery in Egypt.

Rashi (11th century rabbi Shlomo Yitzchaki) wrote that the king of Moab consults the Midianites because he knows Moses spent a period of his life in Midian, and he wants to learn more about the leader of the Israelites. The elders of Midian choose to not only advise the king of Moab, but join forces with him in the campaign to seduce the Israelite men. According to Rashi, God orders Moses to attack only the Midianites because the Moab acted solely out of fear for their own nation, “but the Midianites became enraged over a quarrel which was not their own”.

Some 20th century commentary explains the conflation between Moabites and Midianites by concluding that Midian was not a separate kingdom, but a confederation of nomadic tribes. (This explains why the first Midianites Moses meets lived near Mount Sinai, while the Midianites in the book of Numbers live in or near Moab, several hundred miles away.) According to this theory, King Balak recruits local Midianite elders in order to involve all the people living in Moab, and the two ethnic groups work together to weaken the Israelites.

This theory explains God’s order to kill the Midianites, but does not explain why God fails to order the death of Moabites who are not Midiainites.

The Scientists

The commentators I call “the scientists” use linguistic and archeological evidence to assign various parts of the biblical text to authors from different periods and with different agendas. Inconsistencies in a Torah story occur when two different sources are awkwardly combined by a redactor.

The “documentary hypothesis” about when various pieces of the Bible were written has been revised a number of times since it first became popular in the 19th century, but linguistic scholars have agreed that passages in the first five books of the Bible come from at least four original documents (and probably additional fragments), and were stitched together and edited by at least one redactor.

Richard Elliott Friedman’s The Bible with Sources Revealed (2003) proposes that the stories in the Torah portions Balak, Pinchas, and Mattot came from three different sources which were compiled and edited by a final redactor (perhaps the priest called Ezra the Scribe).

The two references to Midian (…to the elders of Midian…in Numbers 22:4; … and the elders of Midian … in Numbers 22:7) were inserted into the Bilam story by the final redactor who compiled and edited the five books of the Torah in the 5th century B.C.E. This redactor (possibly Ezra) inserted the elders of Midian into the Bilam story in order to harmonize it with the later story of seduction by Midianite women.

According to Friedman, the bulk of the Torah portion Balak was written by the “E” source in the northern kingdom of Israel. The northern kingdom was often in conflict with Moab across the Jordan River, and at one point conquered the whole country, only to be defeated by a new king of Moab named Mesha. The “E” source considered Moab an enemy.

Friedman credits the redactor of J/E with writing the story of the Moabite women seducing the Israelites into worshiping Baal Peor. The J/E redactor combined the “E” scripture from the northern kingdom of Israel with the “J” scripture from the southern kingdom of Judah, and added a few other stories—including the story of the Moabite women, according to Friedman.

The “P” source, which Friedman assigns to the Aaronide priests at the time of King Hezekiah of Judah, wrote the next story, in which a man from the tribe of Shimon and the daughter of a Midianite king go into the Tent of Meeting to copulate, and are speared in the act by Aaron’s grandson Pinchas. God then makes a covenant with Pinchas, and tells Moses to attack the Midianites.

Friedman notes that the “P” source was responding to a conflict at the time between priests who claimed descent from Aaron, and a clan of Levites called “Mushi” who may have been descendants of the two sons of Moses and his Midianite wife, Tzipporah. The first book of Chronicles, written between 500 and 350 B.C.E., says their descendants were the Levites in charge of the treasury. This story by “P” praises Aaron’s grandson, while denigrating Midianites.

In the next Torah portion, Mattot, the “P” source records the story of the Israelite’s war on the five kings of Midian, and has Moses blame the Midianite women for causing Israelite men to worship Baal Peor.

The approach used by Friedman and other scientific commentators certainly explains why this part of the book of Numbers keeps adding or replacing Moabites with Midianites. But it does not address the psychological insights of the stories when they are read as if they are episodes in a novel or mythic epic.

The Psychologists

The commentators I call “the psychologists” read the Bible as it stands, viewing it as a collection of mythic tales rolled into one grand epic, and mine it for insights about human nature.

One of the first psychological commentaries appears in a 5th century C.E. story in the Midrash Rabbah for Numbers. Referring to the Torah story about an Israelite man bringing a Midianite princess into the Tent of Meeting for sex, the Midrash says: “He seized her by her plait and brought her to Moses. He said to him: ‘O son of Amram! Is this woman permitted or forbidden?’ He answered him: ‘She is forbidden to you.’ Said Zimri to him: ‘Yet the woman whom you married was a Midianitess!’ Thereupon Moses felt powerless and the law slipped from his mind. All Israel wailed aloud; for it says, they were weeping (25:6). What were they weeping for? Because they became powerless at that moment.”

As a psychological commentator myself, I would point out that until the Israelites reach the Jordan north of Moab, all their contacts with Midianites have been positive. Moses himself is sheltered by a Midianite priest, Yitro, when he is fleeing a murder charge in Egypt. Yitro becomes his beloved mentor and father-in-law. The Torah does not say Moses loves his wife, Yitro’s daughter Tzipporah, but she is the mother of his two sons, and she does rescue him from death on the way back to Egypt.

When Moses is leading the Israelites from Egypt toward Mount Sinai, his Midianite family arrives at the camp, and Moses greets his father-in-law with joy and honor. Yitro calls the god of Israel the greatest of all gods, makes an animal offering to God, and gives Moses good advice about the administration of the camp. (Exodus 18:5-27)

Moses and the Israelites do not encounter Midianites again until 40 years later, about 500 miles to the northeast, and in the book of Numbers. These Midianites are hostile instead of benevolent, determined to ruin the Israelites by alienating them from their god.

Does Moses feel betrayed by the people he married into? Does he feel powerless, as the Midrash Rabbah claims, when his own affiliation with Midian seems to contradict his orders to destroy Midian?

Does it break his heart to see Midianite women, kin to his own wife, seducing Israelite men away from God? Does it break his heart to transmit God’s orders to kill all the Midianites near Moab, including the captive women?

Does he turn against his own Midianite wife and sons then?

Or does he reassure himself, and perhaps others, that the Midianite tribes in Moab are different from the Midianite tribes near Mount Sinai; that there are good Midianites and bad Midianites, and it is right to marry the good ones, and kill the bad ones?

If Moses distinguishes between good Midianite tribes and bad Midianite tribes, does it occur to him that within a tribe there might be good and bad individuals? That wholesale slaughter, although the usual procedure in war, is actually unjust because a number of innocent people die with the guilty?

Judging by Moses’ long speech to the Israelites in the book of Deuteronomy (which scientific commentators attribute to sources written after 640 B.C.E.), Moses and the Torah continue to condemn tribes and nations wholesale, without regard for individual members.

Just as Moses judges all Midianites in the five northern tribes as evil because of the actions of a few of their members, human beings throughout history have made judgements about undifferentiated groups. It is so much easier than discriminating among individuals. From Biblical times to the present day, some people have judged all Jews as bad.

Today, I catch myself ranting against Republicans, as if every person who voted Republican in the last election were responsible for the particular propaganda efforts and political actions that I deplore. A psychological look at the story of Moses and the Midianites near Moab reminds me that I need to be careful not to slander the innocent with the guilty.

Note: This blog completes the book of Numbers for this year (2015 in the modern calendar, 5775 in the Hebrew calendar). My next blog post will be in two weeks, when we open the book of Deuteronomy.