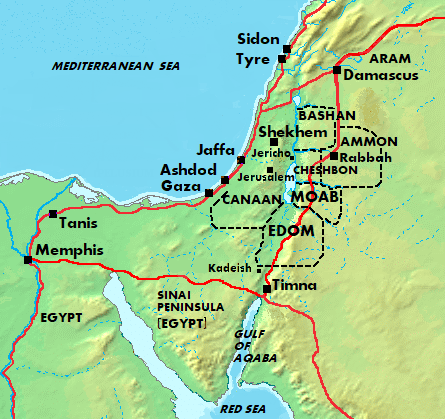

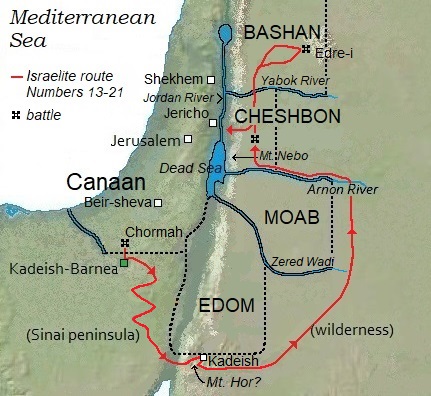

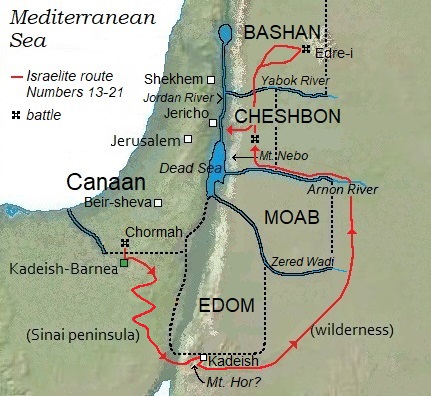

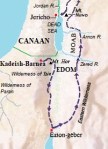

When the Israelites refused to march into Canaan, God doomed them to remain in the wilderness for 40 years before they could try again.1 In this week’s Torah portion, Chukat (Numbers 19:1-22:1), the 40 years are almost over. Moses leads the next generation of Israelites toward Canaan—but he takes a different route. Instead of heading due north into the Negev Desert again, he leads the people east to the border of Edom, hoping they can then travel north on the king’s highway that runs east of the Dead Sea, then cross the Jordan River into a different part of Canaan.

This route would take the Israelites through the heart of the kingdom of Edom, then through the kingdom of Moab, and finally through the Amorite kingdom of Cheshbon. After almost 40 years in the wilderness, they would walk through settled land with towns and governments.

The journey does not go the way Moses hoped. None of the first encounters between the kings and the Israelites result in cooperation. But the responses on both sides vary, depending on the degree of respect versus belligerence.

One definition of “respect” is due regard for the feelings and rights of others. The opposite of respect is contempt, the assumption that the other is not worth bothering to treat as an equal. Contempt can lead to condescension, but it can also lead to belligerence, since the contemptuous person considers the other an easy mark.

Encounter with Edom

And Moses sent messengers from Kadeish to the king of Edom: “Thus says your brother Israel: You know all the hardship that found us: that our ancestors went down to Egypt, and we lived in Egypt a long time, and the Egyptians were bad to us and to our ancestors.” (Numbers 20:14-15)

kadeish (קָדֵשׁ) = a place name from the adjective kadosh (קָדוֹשׁ) = holy (in the Israelite religion); a male cult prostitute (in other religions in the area).

Moses calls the people Israel the “brother” of the Edomites to remind the king that in the old Genesis story, Esau (a.k.a. Edom) and Jacob (a.k.a. Israel) are twin brothers.2 Kinship alone suggests that the Israelites and the Edomites should be allies, treating one another with friendship and respect. Moses’ message continues:

“And we cried out to God, and [God] listened to our voice and sent a messenger, and we went out from Egypt. And hey, we are at Kadeish, a town on the edge of your territory.” (Numbers 20:16)

Moses is giving the king of Edom another reason to treat the Israelites respectfully: God pays attention to them and sends a divine messenger to help them. The name of their current location, Kadeish, implies that they are still under God’s protection.

Next comes Moses’ extremely respectful initial request:

“Please let us cross your land! We will not cross through field or vineyard, and we will not drink well water. We will go on the derekh hamelekh. We will not spread out to the right or left until we have passed through your territory.” (Numbers 20:17)

derekh hamelekh (דֲֶּרֶךְ הַמֶּלֶךְ) = the king’s highway. (Derekh = way, road. Hamelekh = the king.)

The “king’s highway” in the Ancient Near East was not private property, but a public thoroughfare maintained by the king for efficient travel between countries, for trade or for war. If a king had the power to prevent troops belonging to one of his enemies from crossing his kingdom on the way to somewhere else, he would so. But kings would permit an ally’s troops to use their section of the highway in order to reach a common foe.

The king’s highway that Moses wants to use in this week’s Torah portion began at the Gulf of Aqaba and ran north through Egyptian territory to the border of Edom; then on through Edom, Moab, and a disputed territory called Cheshbon in the book of Numbers. This highway continued north through Ammon to Damascus before it veered toward northern Mesopotamia. It was by far the fastest route from the eastern Sinai Peninsula to the Jordan River.

But Edom said to him: “You may not cross through me, or else I will go out with the sword to move against you.” (Numbers 20:18)

The king’s refusal includes a threat. He is less respectful than Moses, but still gives him fair warning, treating him as a peer rather than as someone beneath contempt.

The king of Edom uses the first person singular, as if he is synonymous with his country. Moses’ reply is framed first as the response of the Israelites, but then it switches to “I” as if Moses, in turn, is synonymous with the Israelite horde, whom God has promised to turn into a nation.

And the Israelites said to him: “We will go up on the mesilah, and if we drink your water, I or my livestock, then I will pay its price. [My request is] hardly anything! Let me cross on foot.” (Numbers 20:19)

mesilah (מְסִלָּה) = a wide road or highway of packed earth or stone.

Now Moses is proposing to take a different road through Edom. Most commentators propose that this second route went through the mountains, avoiding well-populated areas where the passage of hundreds of thousands of foreigners might spark conflict. Moses remains respectful, and even offers to pay for water from natural streams.

But he said: “You may not cross!” And Edom went out to meet him with a heavy troop and with a strong hand. Thus Edom refused to allow them to cross through his territory, and Israel turned away from him. (Numbers 20:20-21)

The king of Edom does not trust the Israelites, but he does respect them enough to keep his army on his side of the border, and not provoke a battle.

The Israelites also refrain from provoking a battle, though their population includes armed men. When the episode is retold in the book of Deuteronomy, Moses says that God told him:

“Do not oppose them! Because I will not give you of their land as much as the sole of a foot can tread on; because I have given the hills of Seir to Esau as a possession.” (Deuteronomy 2:5)

Edom and Israel do not become allies, but Moses respects the God-given right of the Edomites to their land.

Encounter with Sichon

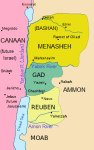

The Israelites march around the kingdom of Edom through unclaimed wilderness and travel north, avoiding the kingdom of Moab as well. They cross the Arnon River and head west toward the Jordan, camping near the border of the Amorite kingdom, a cioty-state called Cheshbon.

And Israel sent messengers to Sichon, king of the Amorites, saying: “Let me pass through your land. We will not turn aside into field or vineyard. We will not drink water from wells. On the derekh hamelekh we will go until we have crossed your territory.” (Numbers 21:22)

The main “king’s highway” headed north to Damascus, but the Israelites could take it most of the way through Sichon’s kingdom—and probably past his capital, Cheshbon—before turning west and heading for the Jordan at Jericho.

Moses is again making a polite and respectful request. But Sichon has no reason to believe the Israelite horde would pass through his own capital peacefully.

And Sichon did not give Israel [permission] to cross his territory; and Sichon gathered all his [fighting] people and went out to meet Israel in the wilderness. And he came to Yahatz3 and he battled against Israel. (Numbers 21:23)

Unlike the king of Edom, who stopped at his own border, King Sichon leads his army into the wilderness and starts a battle with the Israelites. His belligerence reflects contempt; he believes the Israelites will crumble under attack. But he pays for his disrespect.

And Israel struck with the edge of the sword, and took possession of his land from Arnon up to Yabok [River], up to Ammon—since the territory of the Ammonites was strong. And Israel took all these towns, and Israel settled in all the towns of the Amorites, in Cheshbon and in all its dependent villages. (Numbers 21:24-25)

The story then gives a possible reason for Sichon’s contempt.

For Cheshbon was the town of Sichon, who was king of the Amorites. And he had made war against the previous king of Moab, and had taken all his land from his hand as far as the Arnon. (Numbers 21:26)

A man who had defeated the king of Moab and seized the northern part of his kingdom might well feel superior to a nomadic multitude consisting of the descendants of slaves.

And Israel settled in the land of the Amorites. And Moses sent [men] to scout out Yazeir, and they captured its dependent villages and dispossessed the Amorites who were there. (Numbers 21:31-32)

Now the Israelites own the land that used to be northern Moab. At this point, they could simply march west to the Jordan River and prepare to invade Canaan, the region God had promised would become their homeland. But they do not.

Encounter with Og

They turned their faces and went up the derekh of the Bashan. And King Og of the Bashan to meet them, he and all his [fighting] people, for war at Edre-i. (Numbers 21:33)

The Israelites (or perhaps only a large force of Israelite men) march north on a subsidiary highway into a different Amorite kingdom, Bashan. Moses does not send a message to King Og of Bashan; after all, the Israelite horde does not need to cross his country to reach their destination. The Israelites simply seize an opportunity to conquer more land.

Their action shows no respect for the people of Bashan. Encouraged by their conquest of Sichon’s kingdom, the Israelites now feel superior to Amorites in general, and their contempt makes them belligerent. Perhaps the Israelites only feel respect toward the peoples who have a historic tie of kinship with them.

And the God character in this week’s Torah portion approves.

And God said to Moses: “Do not be afraid of him, because into your hand I give him and all his people and his land. And you will do to him as you did to Sichon, king of the Amorites, who sat in Cheshbon.” (Numbers 21:34)

So the Israelites defeat King Og and take over his country, too.

Having taken possession of both of the small kingdoms surrounded by Ammon on the east, Moab on the south, and Canaan to the west and north,

The Israelites traveled on and camped on the plains of Moab, across from the Jordan of Jericho. (Numbers 22:1)

They camp where they can see across the river to Canaan, a big patchwork of city-states they will eventually conquer, like Bashan, without even warning the current residents. But they spend some time first on the “plains of Moab”, so-called because that land belonged to Moab before Sichon conquered it.

In the world of the Torah, and in the world today, conquest and lack of respect for national boundaries, or for the feelings and rights of the citizens within those nations, is the norm.

When so many nations treat one another with contempt and belligerence, we cannot be surprised to encounter bullying and condescension from individuals. Will we ever learn respect?

- Numbers 13:30-14:45 . See my post Shelach-Lekha: Sticking Point.

- Moses ignores the fact that in the Genesis story (Exodus 25:24-34, 27:1-45), Esau and Jacob are rivals for the rights of the firstborn in that story, and struggle with one another from birth to old age.

- Yahatz is mentioned on the Mesha Stele erected in the 9th century BCE by King Mesha of Moab. The stele records that Moab won a battle against the northern Kingdom of Israel and captured the town of Yahatz, which the Israelites had built up.