When characters in the Torah hear God speak, some simply obey. Others some talk back to God, either to ask questions or to make excuses. In this week’s Torah portion, Vayeira (Genesis 18:1-22:21), Avraham raises talking back to God to a new level.

Bereishit: shifting the blame

The first human being to whom God speaks is the first human being: the adam (אָדָם = human being) in the first Torah portion of Genesis/Bereishit (Genesis 1:1-6:8). The God character warns the adam that eating from the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil would result in death.

Nothing happens. I suspect that the human does not understand, never having seen anything die, but nevertheless follows God’s advice and avoids the Tree of Knowledge. Then God separates the human into male and female, and provides a talking snake. Finally the two humans eat the fruit.

The next time they hear God in the garden, they hide. Then God asks:

“Where are you?” (Genesis 3:9)

The male human answers:

“I heard your sound in the garden, and I was afraid because I am naked, and I hid.” (Genesis 3:10)

Before the two humans ate the fruit, they did not notice they were naked; so were all the other animals in Eden. But once they know that some things are good and some are bad, they become self-conscious. (See my post Bereishit: In Hiding.) God asks:

“Who told you that you are naked? From the tree about which I ordered you not to eat, did you eat?” And the human said: “The woman whom you gave to be with me, she gave to me from the tree, and I ate.” (Genesis 3:11-12)

The man admits that he ate from the tree, but only after blaming the woman. When God questions the woman, she blames the snake. Then the God character “curses” the snake, the woman, and the man with the ordinary hardships of life outside the mythical garden of Eden, and expels them from the garden so that they will not eat from the Tree of Life and become immortal.

Throughout the conversation, the God character is the authority figure, and the two humans are like children making excuses to avoid being blamed and punished.

Bereishit: lying and begging

The next human God speaks to is the oldest child of the first two humans, Kayin (קַיִן, “Cain” in English). He makes a spontaneous offering to God, and his younger brother Hevel (הֶבֶל, “Abel” in English) follows suit. Kayin gets upset because God only pays attention to Hevel’s offering. Then God warns Kayin to rule over his impulse to do evil, but the warning goes over Kayin’s head.

And it happened when they were in the field, and Kayin rose up against his brother Hevel, and he killed him. Then God said to Kayin: “Where is Hevel, your brother?” And Kayin said: “I don’t know. Am I my brother’s shomeir?” (Genesis 4:8-9)

Shomeir (שֺׁמֵר) = watcher, guard, protector, keeper.

Kayin certainly knows where he left Hevel’s body, so his answer “I don’t know” is a lie. He might not have understood what death is before he killed his brother, but he knows now, and he suspects that he did something wrong. So he lies in an effort to escape being blamed.

Next Kayin asks what might be an honest question. Was he supposed to watch over his brother, the way he tends his vegetables and Hevel used to tend his sheep?

On the other hand, his question might be a protest that he is not responsible for protecting his brother, so he should not be blamed for what happened when he “rose up against” Hevel.

The God character does not bother to answer. Instead God curses him with a life of wandering instead of farming. Kayin cries out in alarm:

“My punishment is too great to bear! … Anyone who encounters me will kill me!” (Genesis 4:13-14)

Kayin might be thinking that his future relatives will be angry with him, and kill him the way he killed Hevel.

Then God said to him: “Therefore, anyone who kills Kayin, sevenfold it will be avenged!” And God set a sign for Kayin, so that anyone who encountered him would not strike him down. (Genesis 4:15)

Once again, the God character is the authority figure. Kayin lies to avoid being blamed, but he also (indirectly) begs God for protection, which God provides.

Lekh-Lekha: doubting

The next human to whom God speaks is Noach (נֺחַ, “Noah” in English). God gives Noach orders, and Noach follows them without a word. (See my post Noach: Silent Obedience.) There are no questions.

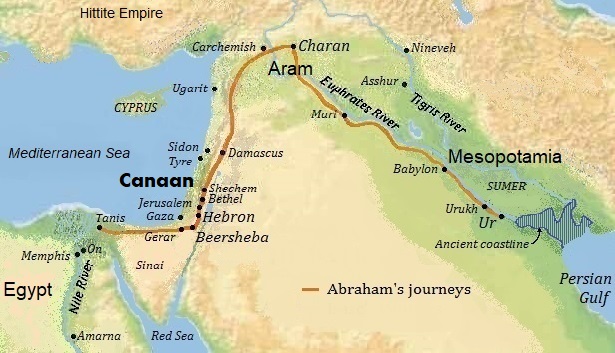

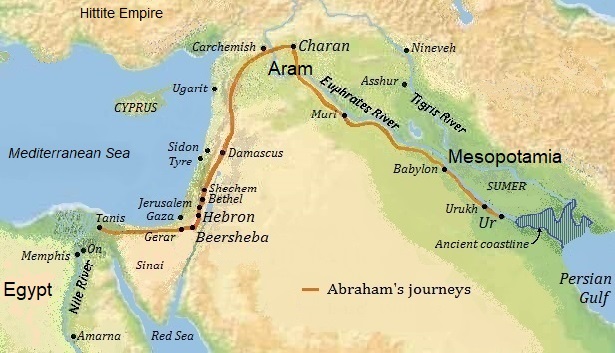

Avram (אַבְרָם, “Abram” in English) begins his relationship with God on the Noach model. But after God has promised him twice that he will have vast numbers of descendants,1 and twice that his descendants will own the land of Canaan,2 Avram cannot resist speaking up. He points out that at age 75 he is still childless. Then he asks God for more than verbal promises.

“My lord God, how will I know that I will possess it [the land]?” (Genesis 15:8)

The God character responds by staging an elaborate covenant ceremony. (See my post Lekh-Lekha: Conversation.) At its conclusion, God repeats once more that Avram’s descendants will own the land of Canaan.

When Avram is 86, he has a son by his wife Sarai’s servant Hagar, and names the boy Yishmael (יִשְׁמָעֵאל, “Ishmael” in English). Although a divine messenger speaks to Hagar when she is pregnant,3 God does not speak to Avram again until he is 99 years old. Then God manifests to him and announces:

“I am Eil Shadai! Walk about in my presence, and be unblemished!” (Genesis 17:1)

Eil Shadai (אֵל שַׁדַּי) = God who is enough, God of pouring-forth, God of overpowering.

This is the first use in the bible of the name Eil Shaddai. This name for God occurs most often in the context of fertility. Here, the name might encourage Avram to believe God has the power to make even a 99-year-old man and his 89-year-old wife fertile. God continues:

“I set my covenant between me and you, and I will multiply you very much.” (Genesis 17:2)

Avram responds by silently prostrating himself. He already has a covenant with God, and the only multiplication that has happened during all the years since is the birth of Yishmael.

But God outlines a new covenant, this time one in which both parties have responsibilities. First there is the question of names: just as God is now Eil Shadai, Avram will henceforth be Avraham (אַבְרָהָם; “Abraham” in English),

“… because I will make you the av of a throng of nations!”

av (אַב) = father. (Raham is not a word in Biblical Hebrew.)

The God character expands on the usual theme, promising that Avraham’s descendants will include many kings, and they will rule the whole land of Canaan. In return, Avraham must circumcise himself and every male in his household, including slaves, and so must all his descendants.

Next God changes the name of Avraham’s 89-year-old wife from Sarai to Sarah (שָׂרָה = princess, noblewoman), and promises to bless her so that she will bear Avraham a son.

But Avraham flung himself on his face and laughed. And he said in his heart: “Will a hundred-year-old man procreate? And if Sarah, a ninety-year-old woman, gives birth—!” (Genesis 17:17)

In other words, Avraham does not believe God, who has been making the same promise for years. But he does want blessings for the thirteen-year-old son he already has from Hagar.

And Avraham said to God: “If only Yishmael might live in your presence!” (Genesis 17:18)

Then God promises that Yishmael will also be a great nation, but the covenant will go through Avraham’s son from Sarah, who will be born the following year and will be called Yitzchak (יִצְחָק = he laughs; Isaac in English). The God character noticed when Avraham laughed.

The Torah portion closes with Avraham circumcising himself and all the males in his household, including Yishmael. Whether Avraham believes Sarah will give birth or not, he wants to fulfill his own part of the covenant. Why would he risk upsetting God?

In the portion Lekh-Lekha, the God character is more powerful than the man, and Avram/Avraham is careful not to incur God’s displeasure–but he has his own opinions.

Vayeira: teaching

This week’s Torah portion, Vayeira, opens when Avraham sees three men approaching his tent. At least they look like men, and Avraham lavishes hospitality upon them as if they were weary travelers. But the “men” turn out to be divine messengers. Through one of them, God speaks to both Avraham and Sarah, announcing that Sarah will give birth the next year. (See my post Vayeira: On Speaking Terms.)

Then Avraham walks with the three “men” to a lookout point, where God says:

“The outcry of Sodom and Gomorrah is great, because their abundant guilt is very heavy. Indeed I will go down, and I will see: Are they doing like the outcry coming to me? [If so,] Annihilation! And if not, I will know.” (Genesis 18:20-21)

Two of the divine messengers continue down to Sodom to see if its people really are as evil as God has heard,4 while God stays with Avraham at the lookout.

Avraham came forward and said: “Would you sweep away the tzadik with the wicked? What if there are fifty tzadikim inside the city? Would you sweep away and not pardon the place for the sake of the fifty tzadikim who are in it? Far be it from you to do this thing, to bring death to the tzadik with the wicked! Then the tzadik would be like the wicked. Far be it from you! The judge of all the earth should do justice!” (Genesis 18:23-25)

tzadik (צַדִּיק) = righteous, innocent. tzadikim (צַדִּיקִם) = people who are righteous or innocent.

This is a new thing in the world: a human being arguing with God and telling God the right thing to do.

Is Avraham the teacher now, and the God character his pupil? How does God react?

See my post next week: Vayeira: Persuasion.

- Genesis 12:2, 13:16.

- Genesis 12:7, 13:15-17.

- Genesis 16:7-12. See my post Lekh-Lekha: First Encounter.

- The God character in the Torah is not omniscient.