And Abraham expired and died at a good old age, old and saveia, and he was gathered to his people. (Genesis 25:8)

saveia (שָׂבֵעַ) = (adjective) satisfied, full, sated. (From the root verb sava, שָׂבַע = be sated, have enough, be filled up—usually with food.)

The full and satisfying end of Abraham’s life in this week’s Torah portion, Chayei Sarah (“The Life of Sarah”, Genesis 23:1-25:18) contrasts with the thin and bitter end of King David’s life in the accompanying haftarah reading (1 Kings 1:1-1:31). The haftarah sets the tone for King David’s final years when it opens:

And the king, David, was old, coming on in years, and they covered him with bedclothes, but he never felt warm. (1 Kings 1:1)

In their prime, both men have motley careers: brave and magnanimous in one scene, heartless and unscrupulous in the next. But in old age (about age 140-175 for Abraham, 60-70 for David) their paths diverge.

Abraham’s prime

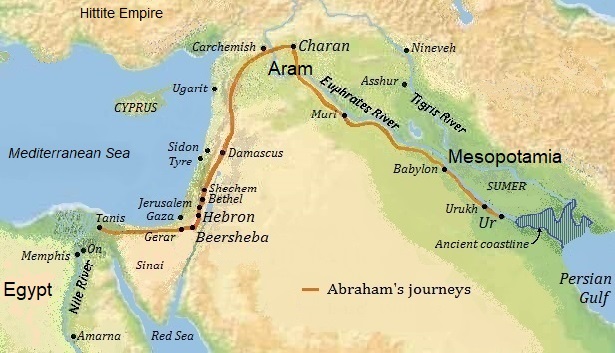

Abraham commits several major unethical deeds after he moves his family to Canaan when he is 75. Although his behavior toward his nephew Lot is faultless, his behavior toward his wife Sarah and his first two sons, Ishmael and Isaac, is sometimes cruel, selfish, and immoral.

Twice when he travels to a new kingdom, Abraham asks Sarah to pretend to be his sister. He claims that she was unusually beautiful1 and that the king has peculiar morals, considering adultery taboo, but murder perfectly all right. The king will take Sarah regardless, but only if everyone lies and says Abraham is her brother will the king let him live. In fact, both kings pay Abraham a bride-price for his “sister”. Both kings are horrified when they discovered the truth. Both times, Abraham gets to take back his wife and leave richer than when he arrived.2

Sarah also uses Abraham, by giving him her slave Hagar as a concubine for the purpose of producing an heir. (She is 75 and childless at the time.) After Sarah give birth to her own son at age 90, she sees that Hagar’s son Ishmael is not treating her son Isaac with respect. So she orders Abraham to cast out Hagar and Ishmael, in order to make Isaac the only heir. Abraham is rich, and could easily give his own son and his former concubine a couple of donkeys laden with water, food, and silver to ensure their safe relocation. Instead, Abraham sends them off into the desert with only bread and a skin of water. When they get lost and use up the water, Ishmael nearly dies.3 God arranges a rescue, but Abraham never sees his oldest son again.

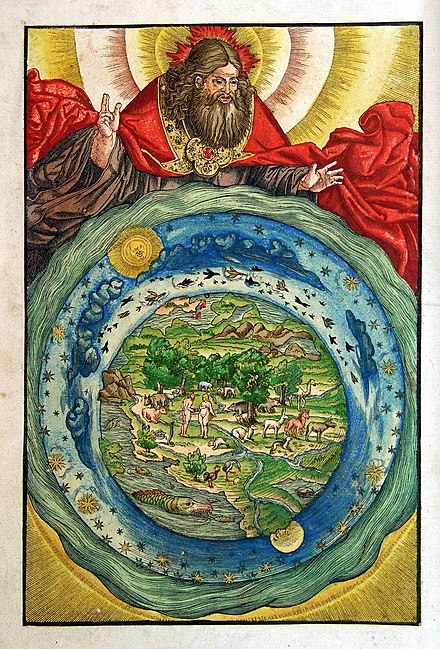

Isaac has grown up, but has not yet married or had children, when Abraham hears God tell him:

“Please take your son, your only one, whom you love, Isaac. And get yourself going to the land I will show you, and offer him up there as a burnt offering on one of the hills, which I will say to you.” (Genesis 22:2)

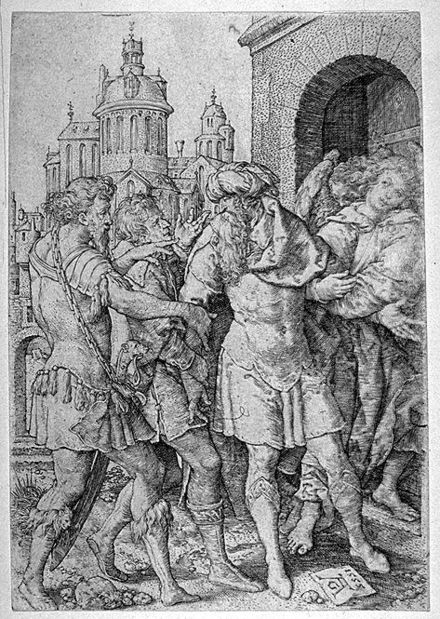

Abraham knows he could argue with God. When he was 99, he argued with God about destroying Sodom, and God listened and agreed it would be unjust to annihilate the city if it contained even ten innocent people.4 Yet now, in his 130’s, Abraham does not argue with God. he does not even ask God a question. He gets up early and leaves with Isaac, two servants, and a donkey carrying firewood, without telling Sarah where they are going. When Isaac lies bound on the altar and Abraham lifts the knife, God has to call his name twice to get him to stop. After Abraham sacrifices a ram instead, he walks back down the hill alone.5 The breach between father and son is irreparable. Abraham never sees Isaac again.

Abraham’s old age

Is Abraham consumed by guilt and loss during the final stage of his life, from his late 130’s to his death at 175? No. But he has changed. This week’s Torah portion, Chayei Sarah, portrays a man at peace with himself who meets all his responsibilities and also enjoys life.

The Torah portion begins with Sarah’s death in Hebron. Yet the last we knew, Abraham was living in Beersheba.6 Perhaps the two locations reflect a glitch in a redactor’s effort to combine two stories. Or perhaps Sarah left her husband after he returned without Isaac and tried to explain what happened. In an already difficult marriage, that would be the last straw. Yet the estrangement does not stop Abraham from traveling to Hebron and doing his duty as Sarah’s husband.

And Abraham came to beat the breast for Sarah and to observe mourning rites. Then Abraham got up from the presence of his dead, and he spoke to the Hittites, saying: “I am a resident alien among you. Give me a burial site among you, and I will bury my dead away from my presence.” (Genesis 23:2)

After some negotiations, Abraham buys a plot of land with a suitable burial cave, and buries Sarah there. In this way he also prepares for his own burial, and future burials in his family.

Isaac is not mentioned during the first scene in Chayei Sarah. But in the next scene, Abraham makes arrangements for Isaac’s marriage.

And Abraham said to his elder servant of his household, the one who governed all that was his: “Please place your hand under my yareikh, and I will make you swear by God, god of the heavens and god of the earth, that you do not take a wife for my son from the daughters of the Canaanites amidst whom I am dwelling. For you must go to the land I came from and to my relatives, and you must take a wife for my son, for Isaac.” (Genesis 24:2-4)

yareikh (יָרֵךְ) = upper thigh, buttocks, genitals.

This is a serious oath. Isaac is in his late thirties at this point, and his father has obviously been keeping track of him from a distance. Now Abraham wants to make sure, before he dies, that Isaac marries and starts producing the descendants God promised. But he does not try to confront his estranged and traumatized son in person. He instructs his steward, and trusts him to deliver the right bride to his son.

Arranged marriage was the norm in the Ancient Near East, so Isaac is not shocked when his father’s steward arrives with a young woman for him. In fact, he falls in love with her.7

Once Isaac is married, Abraham takes a concubine again, and has six sons with Keturah.

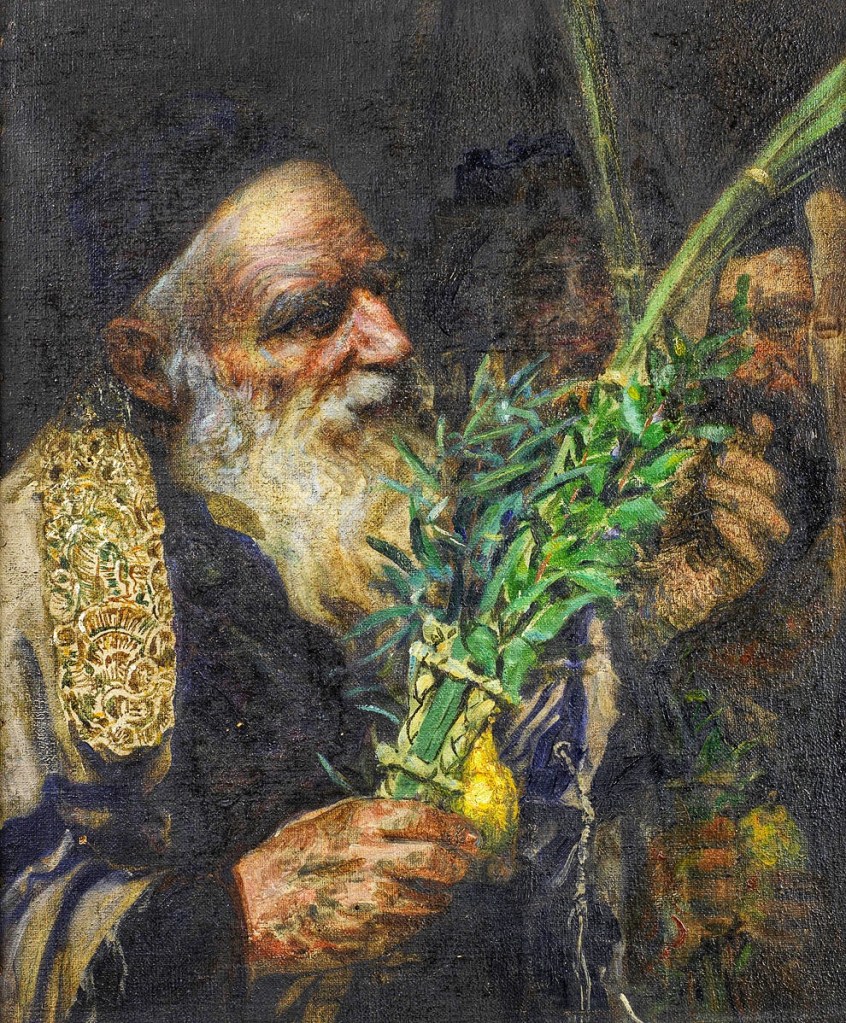

And Abraham gave all that was his to Isaac. But to the sons of the concubines that were Abraham’s, Abraham gave gifts, and he sent them away from his son Isaac while he was still alive, eastward, to the land of the east. And these are the days of the years of Abraham, that he lived: 175 years. And Abraham expired and died in good seivah … (Genesis 25:6-8)

Abraham is virile and enjoys life his old age. He is also in charge of his own life, and takes care to meet all his responsibilities well before he dies. He divides his wealth among his sons and makes sure Isaac will not be harassed by his stepbrothers. After his death, Ishmael and Isaac bury their father in the cave he bought for Sarah’s burial. Whatever mistakes he made before the age of 140, Abraham leads an enviable life for his last 35 years. He is fortunate to be in good health, with both virility and a sound mind. He knows what he is doing, and he does it more thoughtfully than he used to. Abraham was always good at generating plans. But during the last part of his life, his plans are more reasonable, and take the other people in his life into consideration.

No human being is perfect. We may not commit such extravagant misdeeds as Abraham, but we have all hurt other humans. Occasionally we get the blessing of a frank conversation with someone we hurt, and an opportunity to apologize and make amends. But often the chance for a frank conversation never comes. Then the best we can do is to acknowledge our misdeeds to ourselves, and plan how we will behave more ethically in the future. Sometimes we can notice our own improvement, and find peace in our old age.

Perhaps this is what Abraham does in the book of Genesis. He never apologizes to Sarah, or Ishmael, or Isaac. But after age 140, he is careful to meet his responsibilities to everyone, even the people estranged from him. Abraham still pursues his own interests and arranges a pleasant life for himself, but he does it without any deceit and without endangering anyone’s safety. He dies old and satisfied.

Next week, in Part 2, we will look at the unfortunate counterexample of King David’s old age.

- Sarah is 65 when Abraham pulls this scam on the king of Egypt in Genesis 12:10-20. She is 89 when he repeats it with the king of Gerar in Genesis 20:1-18, but during that year God is presumably making Sarah’s body younger so she can bear a son to Abraham.

- See my posts The Wife-Sister Trick: Part 1 and Part 2.

- Genesis 21:8-19. See my post Vayeira: Failure of Empathy.

- Genesis 18:16-32.

- Genesis 22:1-19. See my post Vayeira: Stopped by an Angel.

- In Genesis 22:19 Abraham comes back to Beersheba without Isaac.

- Genesis 25:67.