by Melissa Carpenter, maggidah

By the end of the first Torah portion in the book of Genesis/Bereishit, God regrets creating human beings, and decides to wipe them out. I offered theories about why God thought the human race was spoiled in two of my earlier blog posts: Noach: Spoiled, and Bereishit: Inner Voices. This year, when I reread the Torah portion named after Noah—Noach in Hebrew—I wondered why such a discouraged God made one exception, and saved Noach and his immediate family from the flood.

Last week’s Torah portion ends:

But Noach found favor in the eyes of God. (Genesis/Bereishit 6:8)

This week’s Torah portion, named after Noach, begins:

These are the histories of Noach. Noach was a righteous man; in his generations, Noach walked with God. (Genesis 6:9)

Noach (נֹחַ) = Noah; an alternate spelling of noach נוֹחַ)), a form of the verb nuch (נוּח) = come down to rest, settle down.

The first appearance of the verb nuch in the Torah is when Noach’s ark comes to rest on Mount Ararat at the end of the flood in Genesis 8:4. This is also Noach’s turning point, when he finally begins (at the age of 600) to take some initiative: sending out the birds to test the water level, making an animal offering to God, and planting a vineyard.

Before the flood, God tells His favorite person, Noach, that people are evil and the whole world has been spoiled. He gives Noach instructions for making a wooden ark, and says He will flood the earth and destroy all flesh—except for the few humans and animals on the ark.

(I used the pronoun “He” in case because the God character the Torah presents here is quite anthropomorphic, making sweeping generalizations and acting emotionally.)

Later in the Torah, when Abraham is God’s favorite person of the era, and God tells him that He is about to commit genocide, Abraham talks God out of it. He persuades God to refrain from burning up Sodom if there are even ten innocent people in the city. In the book of Exodus, Moses persuades God to give the Israelites a second chance after they worship the Golden Calf.

But Noach is silent. After God has spoken to him, all the Torah says is: And Noach did everything that God commanded him; thus he did. (Genesis 6:22)

God tells Noach to load seven pairs of each of the ritually-pure animals on board, as well as one pair of each of the impure animals. Then He rephrases His plan, saying that He is going make a flood and

… wipe out everything standing on the face of the earth (Genesis 7:4).

Again, Noach is silent. The Torah repeats:

And Noach did everything that God commanded him.

Both times, Noach makes no protest, but only does what God commands. So God floods the earth.

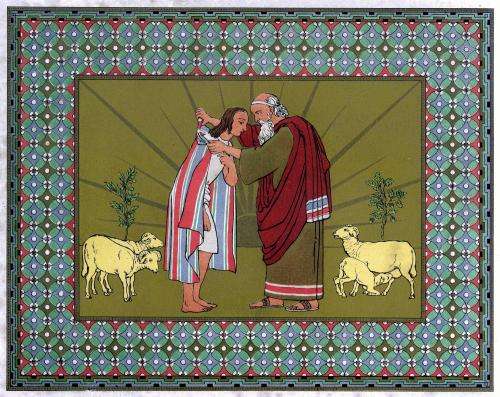

After the flood is over and Noach empties the ark, his first order of business is acting on the hint implied in God’s order to carry seven times as many of the animals that are ritually pure (according to the rules for purity laid out later, in the book of Leviticus/Vayikra).

Then Noach built an altar for God, and he took from all of the ritually-pure animals and from all of the ritually-pure birds; and rising-offerings went up [in smoke] on the altar. And God smelled the nichoach aroma, and God said to His heart: I will not again draw back to curse the earth on account of the human, for the impulse of the human heart is bad in its youth … (Genesis/Bereishit, 8:20-21)

nichoach (נִיחֹחַ) = soothing or pleasing to a god. (The use of this word may be a play on Noach’s name, and may also imply that the god in question will be inclined to come down and rest its presence over the sacrifice.)

Noach’s action puts God in a better mood. God has another change of heart, and views the human condition more optimistically and rationally. According to classic commentary, God decides that it is only natural for children to act on their bad impulses, but adults can learn to control these impulses and be good. So God tells Himself not to overreact to human misdeeds again.

Why does the aroma of Noach’s offering soothe God?

Maybe the God character in the Torah, like other Canaanite gods, loves the smell of burning animals. This would explain why God favored Abel’s animal offering and rejected Cain’s plant offering. It would also explain why slaughtering and burning livestock was the primary method of worshiping God from the time of Genesis down to the fall of the second temple 70 BCE. God really liked that barbecue smell, so that’s what the Israelites gave Him.

On the other hand, maybe God provided Noach with excess ritually-pure animals because He remembered Cain and Abel’s spontaneous offerings, and wanted to make sure Noach had something to offer if he happened to feel spontaneous gratitude for being saved from the flood. The thick clouds of smoke from the combustion of more than 33 kinds of birds and beasts reassures God that Noach does, indeed, feel grateful. So God concludes that adults, at least, can feel and act on good impulses.

So have many commentators, from Philo of Alexandria in the first century C.E. to Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch in the 19th century. But I think both those commentators and the God character in the Torah still had more to learn about human psychology.

Why Noach Burned the Animals

I can imagine Noach acting purely out of fear of this God of wholesale destruction, who cares nothing about innocent children or animals. Noach might well be moved to burn as many animals as possible in the hope of forestalling the Destroyer’s next whimsy.

Another possibility is that Noach acts out of despair. When the flood begins, he had to hustle his own family and the animals he has collected into the ark, then keep everyone else out of it. God closes the door into the ark, but perhaps Noach could still hear the cries of his own neighbors and the sobbing of frightened children.

When the flood waters sink, Noach would see not only mud and broken trees, but floating corpses. He goes ahead and sacrifices the excess ritually-pure animals because he has figured out God wants him to. There is no point in disobeying God now. He wishes he had spoken up earlier, before the earth was destroyed. Did God leave another hint that he missed? Could he have done anything to save more people? Now it is too late, and Noach has to live with himself.

He listens to God’s speech giving instructions for living in the new world, and promising that a flood will never destroy the earth again. But I think Noach is too depressed to care. As soon as God is done talking, Noach plants a vineyard. In the next sentence, he gets drunk.

Some commentators criticize Noach for his silent obedience. But when I reflect on my own life, I know that the number of times I spoke up in favor of justice or mercy were few in comparison with all the times I felt powerless and kept my mouth shut. When the person in authority has absolute power and does not show compassion, it is hard to risk a loss of acceptance, loss of a job, or even loss of one’s life. I can only feel sorry for Noach.

The most frightening thing about the Torah portion Noach is that the person in authority is a god, a god who gets carried away by egotistical emotions and has only a primitive sense of justice. Even today, natural disasters such as earthquakes, hurricanes, and volcanic eruptions can be taken as evidence of a morally deficient god.

That’s why, when I write about these parts of the Torah, I often refer to “the God character”. The anthropomorphic character that the Torah stories refer to by various names of God is simply not the same as the creator of the universe; or the theologians’ omnipotent, omniscient, omnibenevolent being; or the essence and totality of existence; or even the mysterious unknown we sometimes sense with our non-rational minds.

Yet we can still learn from Torah stories in which the God character not only creates and tests and destroys human beings, but also learns from them. There is a God character inside each of our psyches, as well as a Noach, and an Abraham, and maybe even a Moses.