Below is the eighth and final post in my series on why David is God’s favorite king. It is also a post for Yom Kippur, which begins this Wednesday evening.

Yom Kippur

Yom Kippur (יוֹם כִּפּוּר) means “Day of Atonement”. Atonement is a good translation because, like kippur, it means making amends or reparations for something a person or a whole group did wrong. The wrong might be ethical and/or it might be a violation against God. The Torah imagines God as a person who issues lots of rules for behavior, and is offended when we disobey them. One of the ways of imagining God today is as our own inner core, the seat of our conscience, from which we are alienated when we violate what we know inside is right.

The Hebrew word kippur can also be translated as “reconciliation”, since we hope that making reparations will lead to forgiveness and a cleaner, better relationship with the people we have wronged, with God, with ourselves. And historically, the English word “atonement” includes the concept of reconciliation. It was coined in the 16th century out of the words “at” and “one”, to express the idea of reunification.

All humans make mistakes. Some are so inconsequential that as soon as we realize we did something wrong, we can apologize, be forgiven, and be reunited in just a minute or two. Others are more serious.

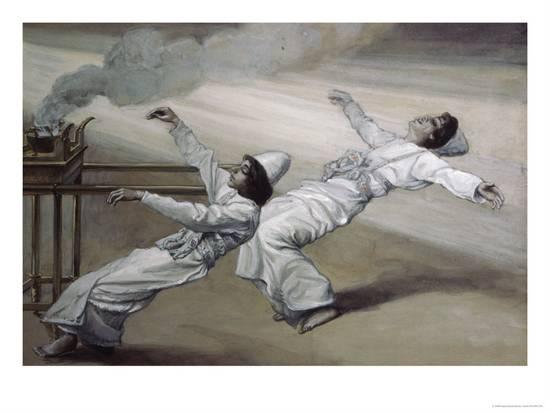

In Ancient Israel, a day was set aside once a year for an elaborate ritual using two hairy goats to atone for the outstanding misdeeds of the whole community. (See my post Yom Kippur: We.) The nature of the ritual changed almost two thousand years ago, when temple sacrifices were replaced with communal prayer. But the purpose of Yom Kippur is the same. Jewish tradition now encourages people to spend the month leading up to Yom Kippur reflecting on their misdeeds against other people and making whatever apologies and reparations we can—as well as working on forgiving those who wronged us. We also reflect on our misdeeds against God—or ourselves—in the hope of finding forgiveness for them on Yom Kippur.

What counts as an immediately forgivable mistake, and what mistake is so serious that its effects are still outstanding when we reach this time of year?

There is a different answer for each person. In the first and second books of Samuel, David commits a number of errors that count as peccadilloes in the fond eyes of God. But then he goes too far.

David’s peccadilloes

When David first flees from King Saul’s attempts to kill him, he lies to the high priest, who then colludes with him to break God’s rule that the sacred bread laid out for God inside the sanctuary can only be eaten later by priests. The high priest gives him five flat loaves, which he eats on his flight. (See my post 1 Samuel: David the Devious.) The God character stands by when King Saul has the high priest killed for letting David escape; David goes unpunished.

When David has become the leader of a large band of outlaws, he runs a protection racket; he guards Nabal’s sheep and shepherds without any previous arrangement, then asks for payment in food. Nabal refuses, and David sets off with 400 of his men with the intention of killing Nabal and every male in his house. Killing an Israelite without a previous court order of execution is so serious a crime that it gets the death penalty.1 Fortunately, Nabal’s wife intercepts David and persuades him that murder would be a bad idea. Since David does not actually commit the crime, God kills Nabal the next day. (See my post 1 Samuel: David the Devious.)

When David and his outlaw band have moved to the Phillistine state of Gat to avoid King Saul, David deceives the king of Gat into believing that he is a trustworthy defector and vassal. He claims that he is raiding Israelite villages and bringing the loot back to the king of Gat, but actually he is getting the loot by raiding Canaanite villages. David leaves no survivors—no one to reveal his deception. (See my post 1 Samuel: David and the King of Gat.) The God character does not object, since in the Hebrew Bible it is perfectly acceptable to make unprovoked attacks on non-Israelite villages and exterminate everyone, as long as the villages are within the boundaries of the land God assigned to the future kingdom of Israel.2

When David is the king of Judah, General Abner unites the rest of Israel under a puppet king and the two sides fight. Then Abner proposes a peaceful reunification, and concludes a treaty with David in which David will become the king of all Israel. But Joab, David’s nephew and general, kills Abner. King David denounces the murder, but does nothing to punish Joab, who remains his general for the rest of David’s life. (See my post 2 Samuel: David the King.) This is a serious mistake for a king, whose job is to dispense justice. But God looks the other way.

From the time he is secretly anointed as Israel’s next king as a young adolescent, until he actually becomes the king of Israel at age 30, David often misses the mark. But he also demonstrates good qualities for a king, such as intelligence, courage, cleverness, eloquence, charm, and solidarity with his followers. And at key times he inquires of God3 and follows God’s advice. So God, who chose him in the first place, continues to help him despite his peccadillos.

Then David goes too far.

David’s unforgiveable act

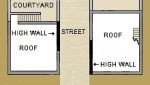

By the time he becomes the king of Israel, David already has seven wives.4 Some years pass while King David builds his new capital in Jerusalem and engages in various conquests. Then, while General Joab and his troops are besieging the capital of the kingdom of Ammon, David goes for an evening stroll on the roof of his palace in Jerusalem.

And from upon the roof he saw a woman bathing. And the woman was very good-looking. And David sent [someone] and he inquired about the woman. And he said: “Isn’t this Bathsheba, daughter of Eliam, wife of Uriyah the Hittite?5” (2 Samuel 11:2-3)

An upright man would sigh and perhaps distract himself with one of his own wives. Adultery is forbidden in the Ten Commandments, and a man who has sex with a married woman gets the death penalty—if he gets caught.6

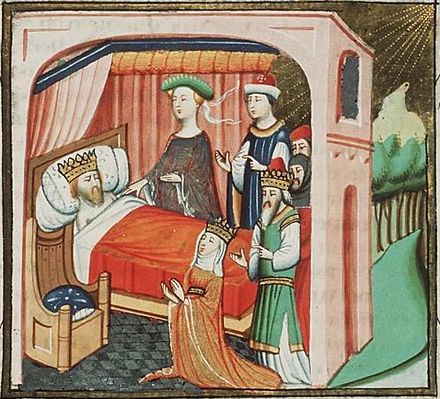

Then David sent messengers and had her taken. And she came to him and he lay down with her. And she had just purified herself from her [menstrual] impurity. And she returned to her house. And the woman became pregnant, and she sent and had it told to David; she said: “I am pregnant!” (2 Samuel 11:4-5)

Bathsheba has just had a ritual bath to purify herself after the end of her period, and her husband is away at the war in Ammon. David’s first thought is that he can still cover up his crime by getting Uriyah to come home and have sex with his wife before her pregnancy shows.

King David summons Uriyah, has a plausible conversation with him about what is happening at the battlefront, then tells him to go home, wash his feet, and relax.

But Uriyah lay down at the entrance of the king’s house with all his lord’s servants, and he did not go down to his own house. (2 Samuel 11:9)

In the morning David asks him why, and Uriyah replies that when his fellow soldiers are camping on the bare ground in Ammon,

“… then I, should I come into my house to eat and to drink and to lie down with my wife?” (2 Samuel 11:11)

Uriyah’s refined moral scruples are blocking David’s unscrupulousness. The next day David gets Uriyah drunk, but the man still refuses the comforts of home. So David sends him back to Ammon with a letter for General Joab: a secret order to put Uriyah in a position where Ammonite soldiers will be sure to kill him. It works; Uriyah is shot down.

And Uriyah’s wife heard that Uriyah, her man, was dead, and she lamented over her husband. And when the mourning period was past, David sent and had her removed to his house, and she became his wife, and she bore him a son. (2 Samuel 11:26-27)

Problem solved, from King David’s point of view. But not from God’s point of view.

And the thing that David had done was evil in the eyes of God. And God sent Nathan to David. (2 Samuel 11:27-12:1)

The prophet Nathan tells King David a parable in which a rich man with many flocks seizes and slaughters a poor man’s only lamb, whom the poor man had nurtured like his own child. Outraged, David declares that the rich man deserves death. Then, probably remembering that the legal penalty for theft is restitution,7 he declares that the rich man must compensate the poor man by paying him four times the price of the lamb—

“—because he did this thing, and since he had no pity!” Then Nathan said to David: “You are the man! (2 Samuel 12:6-7)

The prophet then repeats a long speech by God, including these two key sentences:

“Why have you despised the word of God, to do what is evil in my eyes?” (2 Samuel 12:9)

“Here I am, making evil rise up against you from your own house!” (2 Samuel 12:11)

When the speech is over,

Then David said to Nathan: “I am guilty before God!” And Nathan said to David: “Furthermore God has passed along your guilt. You will not die … the son who was born to you, he will definitely die.” (2 Samuel 12:13-14)

Then God afflicts the baby with sickness, and seven days later he dies. But David and Bathsheba have another son, Solomon, who eventually becomes the next king of Israel.

Atonement

Is it enough for David to realize his crime, admit his guilt, and suffer the punishment of the death of his son? Has he now achieved atonement or reconciliation with God?

No. That would be too easy for such a heinous crime. Evil does indeed rise up against David from his own house. As the Talmud points out,

“The lamb was a metaphor for Bathsheba, and ultimately David was indeed given a fourfold punishment for taking Bathsheba: The first child born to Bathsheba and David died (see 2 Samuel 12:13–23); David’s son Amnon was killed; Tamar, his daughter, was raped by Amnon (see 2 Samuel 13); and his son Avshalom rebelled against him and was ultimately killed (see 2 Samuel 15–18).”8

The character of God does not appear during that whole complicated story. There is no divine interference even when David’s son Avshalom (Absalom) claims Jerusalem, and David is forced into exile. After Joab kills Avshalom in a battle between the two sides, a grieving David laboriously puts his kingdom back in order. After those years of suffering, there is a three-year famine. Then King David finally turns back to God and asks what to do, and God answers.9

The story of King David illustrates that a person who is blessed, like God’s favorite king, can get away with a lot of missteps. But if someone who seems to have a charmed life strays too far from fundamental morality, a chasm opens inside, and it takes many years to find atonement, reconciliation, and reintegration. One Yom Kippur, I believe, is not enough. In this new year of 5786 in the Hebrew calendar, I pray that all those who remember to return to the right path will rejoice to find their feet on it once more. And I pray that those who have gone too far will begin the long journey back.

- Exodus 21:12, Deuteronomy 17:6-12.

- See my post Eikev & Judges: Love or Kill the Stranger?

- See my post 2 Samuel: David the King.

- Mikhal, King Saul’s daughter; Achinoam of Jezreel; Abigail, Nabal’s widow; Maacah, daughter of the king of Geshur; and three wives of unknown provenance from his time as the king of Judah, Chagit, Avital, and Eglah. See 1 Samuel 18:20-27, 2 Samuel 3:2-5.

- He is called “Uriyah the Hittite” to identify his ethnicity. The troops of Israelite kings in the Hebrew Bible often include men from non-Israelite lineages who nevertheless are treated as citizens of Israel. His name is Hebrew: Uri-yah (אוּרִיָּה) = My Light is God.

- Leviticus 20:10.

- The Torah prescribes different amounts of financial restitution for different objects stolen. Exodus 21:37 lists the penalty for stealing a sheep as paying the owner four times the value of the sheep.

- Talmud Bavli, Yoma 22b, William Davidson (Steinsaltz) translation, in www.sefaria.org. The sources in parentheses are included in the text.

- 2 Samuel 21:1.