Moving to another country is risky. You don’t know all the rules, all the dangers. And even if you believe God wants you to go, how do you know you will prosper? If life is not so terrible where you are, isn’t it safer to stay put?

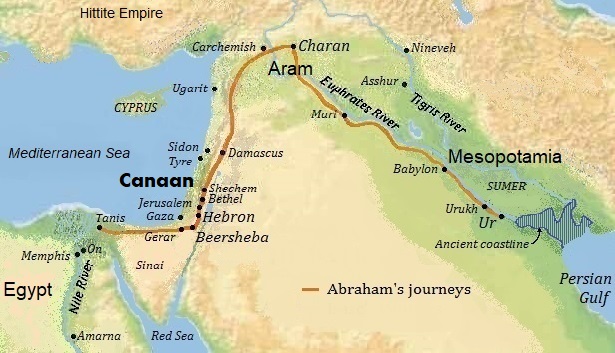

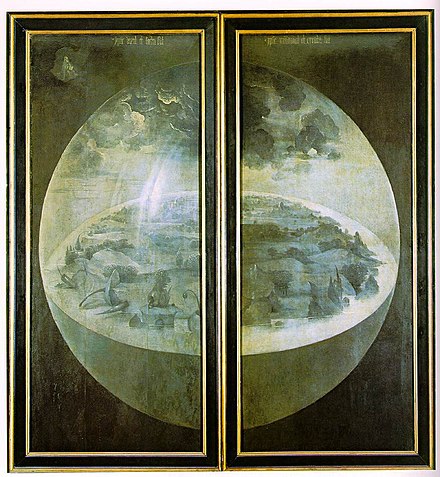

Abraham and his household face the question of emigration in this week’s Torah portion, Lekh-Lekha (Genesis 12:1-17:27). So do the Israelite exiles in the accompanying haftarah reading, Isaiah 40:27-41:16. In both cases, God asks people who live in Mesopotamia to emigrate to Canaan. And God promises to reward them for doing so. But in both cases, there are reasons for doubt.

Lekh Lekha

Last week’s Torah portion, Noach, tells us that Abraham (originally named Avram) has already relocated once. He is the first of three sons Terach begets in Ur, a city in southern Mesopotamia.

And this is the genealogy of Terach: Terach begot Avram, Nachor, and Haran, and Haran begot Lot. And Haran died before his father Terach, in the land of his kin, in Ur of the Mesopotamians. (Genesis/Bereishit 11:27-28)

After naming the wives of Avram and Nachor and mentioning that Avram’s wife Sarai had no children, the story continues:

Then Terach took his son Avram; and his grandson Lot, son of Haran; and his daughter-in-law Sarai, the wife of his son Avram; and they left with him from Ur of the Mesopotamians to go to the land of Canaan. And they came as far as Charan, and they settled there. The days of Terach were 205 years, and Terach died in Charan. (Genesis 11:31-32)

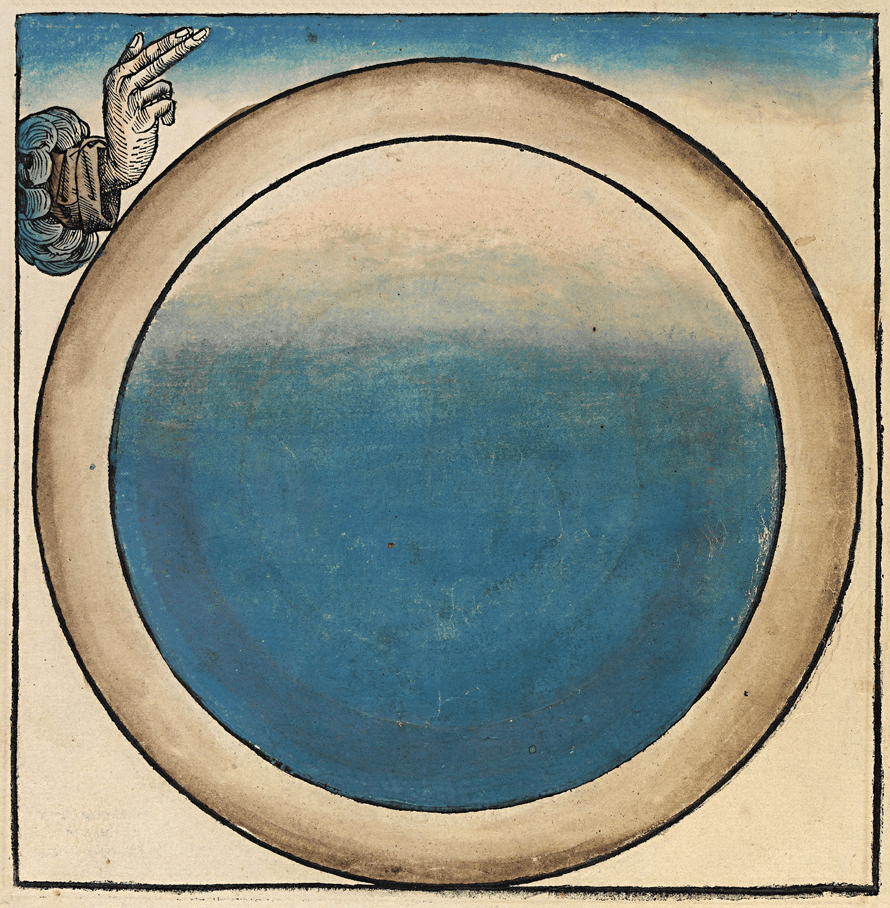

The book of Genesis never says why Terach was heading for Canaan, or why he stops halfway and settles in northern Mesopotamia.

Then God said to Avram: “Go for yourself, from your land and from your kindred and from your father’s house, to the land that I will show you! And I will make you a great nation, and I will bless you, and I will make your name great. Then be a blessing! And I will bless those who bless you, and curse those who demean you. And all the clans of the earth will seek to be blessed through you.” (Genesis 12:1-3)

There are no divine threats that anything bad will happen if Avram does not emigrate to Canaan. Is he tempted by the reward God promises? In the Torah, a blessing from God means longevity, material prosperity, and fertility. A great name means fame. When God makes someone a great nation, it means that person’s descendants will someday own a country.

Avram went as God had spoken to him, and Lot went with him. And Avram was seventy-five years old when he left Charan. (Genesis 12:4)

Since Avram is already 75 and still healthy enough to walk all the way from Charan to Canaan, a journey of about 600 miles or 1,000 kilometers, he could assume he is already set for a long life. He does not need to emigrate to be blessed with longevity.

What about the blessing of prosperity?

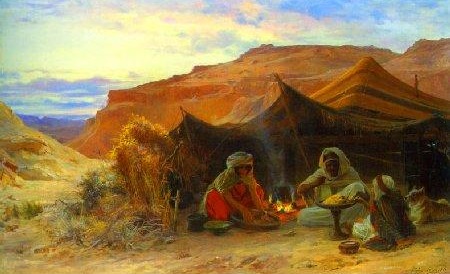

Avram took his wife Sarai and his brother’s son Lot, and all the property that they had acquired, and the people that they had acquired in Charan, and they left to go to the land of Canaan. And they entered the land of Canaan. (Genesis 12:4-5)

Avram, Sarai, and Lot have already acquired a lot of moveable property by the time they emigrate to Canaan, including animals, goods, and slaves.1 They do not need to emigrate to be blessed with material prosperity.

What about the blessing of fertility? We already know Sarai is childless, and we learn later that she is only ten years younger than Avram, so she is 65. Avram has not had any children in Charan, and unless he has a son in old age, he will have no descendants to become “a great nation”.

Perhaps the promise of fertility is the reason Avram obeys God and heads for Canaan. And the rest of his household, including his wife, his nephew, and his employees and slaves, have no say in the matter. They might have (unrecorded) opinions, but in their culture, the male head of household decides for everyone.

Unlike Terach, Avram and his people finish the trip to Canaan. They arrive at a sacred site near the Canaanite town of Shekhem.2

Then God appeared to Avram and said: “To your see [descendants] I give this land.” So he [Avram] built an altar there for God, whom he had seen. (Exodus 12:7)

I imagine that seeing some manifestation of God as well as hearing God speak about descendants again would confirm to Avram that he had made the right choice in following God’s instruction to move to Canaan. Yet when Canaan experiences a famine,

Avram went down to Egypt, lagur there, since the famine was severe in the land. (Exodus 12:10)

lagur (לָגוּר) = to live as a resident alien, to sojourn, to become a migrant.

And God does not object. In fact, God helps Avram pull off a scam that results in pharaoh giving Avram additional animals, silver and gold, and slaves—and ordering men to escort Avram and his household back to the border. (See my post Lekh Lekha, Vayeira, & Toledot: The Wife-Sister Trick, Part 1 and Part 2.)

Avram has further adventures in Canaan, and then the unsolved problem of his lack of descendants comes up again.

After these things, the word of God happened to Avram in a vision, saying: “Don’t be afraid, Avram. I myself am a shield for you; your reward will be very big!” But Avram said: “My lord God, what will you give me? I am going accursed, and the heir of my household is the Damascan, Eliezer!” And Avram said: “To me you have not given seed [a descendant], so hey! The head servant of my household is my heir!” (Genesis 15:1-3)

When the same person says two things in a row, with nothing in between except “And he said”, it indicates a pause while the one being addressed fails to respond. In this case, God does not respond to Avram’s first statement, so Avram adds an explanation.

Then hey! The word of God happened to him, saying: “This one will not be your heir; but rather, the one who goes out from your inward parts will be your heir.” (Genesis 15:4) Another vague promise. So Avram’s wife Sarai tackles the problem herself by arranging for her husband to impregnate her female Egyptian slave. Avram no longer has to have faith that somehow God will provide.

Second Isaiah

Avram at least has the advantage of hearing God tell him directly to emigrate to Canaan from Mesopotamia. When the Babylonian Empire falls, the Israelites living in exile there have only the words of a human prophet who tells them that God wants them to move back and rebuild the razed city of Jerusalem. The prophet is not named, but since the prophecies compose the second half of the book of Isaiah, the speaker is known as “Second Isaiah”. In this week’s haftarah, God declares (through Second Isaiah):

Don’t be afraid, for I am with you.

Don’t look around anxiously, for I am your God.

I will strengthen you.

Also I will help you.

Also I will hold you up by the right hand of my righteousness. (Isaiah 41:10)

The Israelites living in Mesopotamia are anxious about returning to Jerusalem for understandable reasons. Between 597 and 587 B.C.E., while the Babylonian army was conquering the Kingdom of Judah, many Israelites were forcibly deported to Babylon.

Half a century later, when Second Isaiah began prophesying, the new Persian Empire had swallowed up the Babylonian empire. The first Persian king, Cyrus, gave all deportees and children of deportees permission to return to their former homes and rebuild their former temples. But after their traumatic experience, the Israelites are reluctant to believe it would really be safe to move back to Jerusalem. Besides, they saw the city burning down.

Assuring the exiles that their Babylonian conquerors are now powerless, God says:

Hey, everyone who was infuriated with you

will be shamed and humiliated;

They will be like nothingness,

And the men who contended with you will perish. (Isaiah 41:11)

But before the exiles can believe God will eliminate their enemies, they must believe that God is on their side now. And that is hard for people who remember when God failed to rescue them from death and deportation at the hands of the Babylonians. Then God promises to make the Israelites, not just the Persians, a weapon for defeating the Babylonian armies that seem as strong as mountains.

Hey, I will transform you into a new sharp thresher,

An owner of teeth,

You will thresh the mountains

And crush the hills, make them like chaff.

You will scatter them,

And the wind will carry them off,

And a whirlwind will disperse them.

And you, you will rejoice in God

And you will praise the Holy One of Israel. (Isaiah 41:15-16)

The Israelites in Babylonia hear (or read) the prophet’s speeches quoting God. But do they believe the quotes are real? Do they believe God will help them now? Do they set off for Jerusalem?

The book of Isaiah does not give an answer. The conclusion of book of Jeremiah reports that a total of 4,600 people were deported by Babylonian King Nebuchadnezzar.3 (The poorest citizens of Judah were kept in the land to serve as “vine-dressers and field hands”.)4

The book of Ezra describes the return of 42,360 exiles to Jerusalem, along with their 7,337 slaves and 200 singers,5 but the archeological record indicates that the numbers are inflated.

It is also hard to determine how many of the exiles stayed in Babylonia under Persian rule. The city of Babylon had a large Jewish population when Philo of Alexandria wrote in the first century C.E., and had become the center of Jewish law and culture by the time the Talmud was written in the 3rd-5th centuries C.E.6 There is no historical record of a large in-migration of Jews to Babylon, so a lot of deported Israelites and their children must have stayed behind when Ezra and his group set off for Jerusalem.

Believing that God will help you is not so hard when your life has already been good, like Abraham’s. Believing that God will help you is harder when you, or your parents, can remember a time when God failed to rescue you from enemies—enemies who burned your city, killed many of your family and friends, and marched you off to a strange land. Jeremiah explains that God punished the Kingdom of Judah for the bad policies of its kings and for the widespread worship of other gods. Second Isaiah insists that now all that is forgiven.

What would it take for you to believe that God wants you to emigrate? What would it take for you to actually do it?

What if you were a Jew thinking about “making aliyah”—moving to Israel?

- An alternative reading from Talmudic times says that Avram, Sarai, and Lot had not acquired slaves in Charan, but rather made converts. This reading, however, does not fit the society of the time, and is not supported by any other reference in the Hebrew Bible.

- The site is named Eilon Moreh. An eilon (אֵל֣וֹן) is a large and significant tree, the kind that was involved in Asherah worship. Moreh (מוֹרֶה) means “teaching, instruction”.

- Jeremiah 52:30.

- Jeremiah 52:16.

- Ezra 2:65-66.

- Talmudic volumes were written both in Jerusalem (the Talmud Yerushalmi) and in Babylon (the Talmud Bavli), the two centers of Jewish scholarship. The Talmud Bavli is more complete and authoritative.