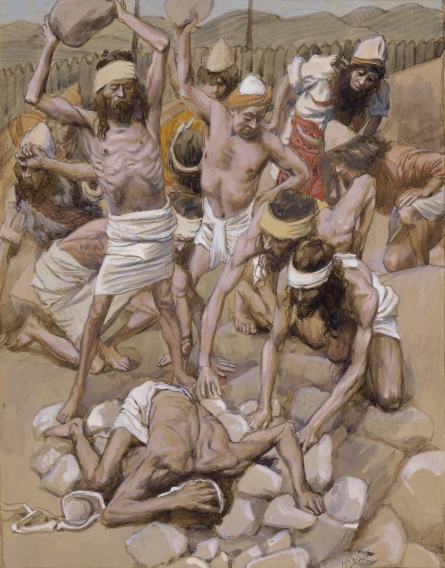

And when the Israelites were in the wilderness, it happened that they found a man collecting sticks on the day of the shabbat. And the ones who found him collecting sticks brought him to Moses and Aaron and the whole community. And they put him in custody, because it had not been explained what should be done to him. Then God said to Moses: “The man must definitely be put the death. The whole community must stone him with stones outside the camp.” And the whole community took him outside the camp and stoned him with stones, and he died, as God had commanded Moses. (Numbers 15:32-26)

shabbat (שַׁבָּת) = day of rest, “sabbath” in English. (From the verb shavat, שָׁבַת = cease, stop.)

Every time I read this week’s Torah portion, Shelakh-Lekha (Numbers 13:1-15:41), this story makes me wince. True, the man is doing labor on Shabbat, and is therefore in violation of one of the “Ten Commandments”:

Remember the day of the shabbat to sanctify it. Six days you may work and you may do all your work. But the seventh day is a shabbat for God, our God; you must not do any work: you, or your son, or your daughter, your male slave or your female slave or your immigrant who is inside your gates. (Exodus 20:8-10)

But what is the penalty for working on Shabbat? Earlier in the book of Exodus, Moses explains that God is providing extra manna on the sixth day because on Shabbat there will be none. Yet some Israelites go out and look for manna to gather on Shabbat anyway. God says:

“How long will you keep refusing to observe my commands and my decrees? See that God gave you the shabbat; therefore he is giving you on the sixth day food for two days. Each man in his spot; do not go out! Each [must stay] in his place on the seventh day!” (Exodus 16:28-29)

This is like a parent saying “I told you not to do that! How long will it take before you listen to me? Don’t do it again!” The Israelites obey the next time, and nobody dies.

But in this week’s portion in Numbers, God pronounces the death sentence for someone who goes out to collect firewood on Shabbat. The punishment does not seem to fit the crime.

The rejection of Canaan

At the beginning of this week’s Torah portion, the Israelites camp within sight of the ridge that separates the desert of Paran from Canaan. Moses follows God’s instruction to send twelve scouts north to explore the land before the people march in and take it over. He tells the scouts to report back on the population, whether their towns are walls, what the soil is like, and whether there are woodlands. He finishes by asking them to bring back some fruit.1

The scouts return carrying pomegranates, figs, and a gigantic cluster of grapes. When they give their report, the Israelites are alarmed to hear that there are large fortified cities in Canaan.2 Then the scouts go outside their instructions and give their own opinions on whether the Israelites will be able to conquer the land God promised to give them. Caleb says yes, but ten other scouts say no. (The twelfth, Joshua, is silent at this point.) The people despair and throw a tantrum, yelling that they would rather die or go back to Egypt than take one step into Canaan. Then everyone sees the glory of God appear as cloud and fire.

And God said to Moses: “How long will this people reject me? And how long will they lack faith in me, despite all the signs that I made in their midst?” (Numbers 14:11)

This is when God decrees that the Israelites must stay in the wilderness for forty years, until the whole generation that left Egypt as adults has died—except for Caleb and Joshua, the two scouts who trusted God. (See my post Shelach-Lekha: Fear and Kindness.)

Then Moses spoke these words to all the Israelites, and the people mourned very much. And they they got up early in the morning and headed up to the top of the highland, saying: “Here we are, let us go up to [attack] the place that God said, because we were wrong.” Then Moses said: “Why are you crossing the word of God? It will not succeed! Do not go up, because God is not there in your midst.” (Numbers 14:39-43)

But the Israelites go anyway, and the Amalekites and Canaanites come down from the hills and soundly defeat them.

The Punishment for Defiance

Even when they realize they did the wrong thing, and should have entered Canaan when God wanted them to, the Israelites do not apologize and wait for God’s next instruction. Instead, they try to erase their bad behavior by staging a replay in order to trigger God into rescind the 40-year delay. And when Moses, God’s prophet, warns them that they have lost God’s support, they defy him and keep going. They are punished for their defiance.

Then the narrative is interrupted for some rules about offerings to God, including the offerings people should make if they discover they have inadvertently failed to obey anything of God’s commands. Next comes a statement about deliberately disobeying a divine command.

But the soul, native or immigrant, who acts with a high hand, it is reviling God. And that soul, nikhretah from among its people. Because it has held in contempt the word of God and broken [God’s] command, hicareit ticareit; that soul’s sin is in it. (Numbers 15:30-31)

nikhretah (נִכְרְתָה) = it is cut down, cut off, eliminated. (A form of the verb karat, כָּרַת = cut off, cut down.)

hicareit ticareit (הִכָּרֵת תִּכָּרֵת) = it must definitely be cut down, cut off, eliminated. (An infinite absolute form of the verb karat.)

Immediately after this comes the example of the man collecting wood on Shabbat.

The implication is that the wood collector knows what day it is, and is deliberately defying the commandment not to work on Shabbat. Therefore he deserves the punishment of being karat.

But it is not clear whether he should be cut off from the community through shunning or exile, or cut down by execution. So the people place him in custody, and God tells Moses that the sentence is death by stoning.

Rest on Shabbat, or die!

I am not surprised that the Talmudic rabbis spent a lot of time figuring out what counts as the kind of work that is prohibited on Shabbat.3 They arrived at a definitive list of 39 categories of forbidden work, and ever since then rabbis have been determining whether a new activity (usually enabled by new technology) falls into one of those categories.

We do not know whether anyone was actually executed for working on Shabbat. According to source criticism, the story of the wood collector appears to be inserted by the P source, and may express a Levitical ideal rather than a reality. But members of strictly observant Jewish communities can still be shunned for disobeying the commandment about Shabbat, and in that sense they are cut off, though not cut down.

I am more interested in the spirit than the letter of the law. Shabbat is supposed to be a day of rest, and also, since the last temple fell in 70 C.E., a day of prayer and pleasure in God’s creation. Besides attending services, reading Torah, and taking a nap, Jews are encouraged to enjoy candlelight, wine, good food, and sex with one’s spouse on Shabbat.

Among the activities the Talmud identifies as prohibited on Shabbat are writing, and doing anything agricultural. Yet what if I am inspired with new insights when I am reading prayers or Torah, and I want to take notes so I will not forget them? Or what if weeding my garden is, for me, a peaceful and meditative break from work that fills me with appreciation for God’ creation?

What if I have no intention of defying God when I go off by myself to engage in the meditative activity of collecting sticks?

- Numbers 13:17-20.

- Numbers 13:28.

- The 39 categories are listed in Mishnah Shabbat, circa 200 C.E., based on the activities the Israelites did to build the sanctuary for God in Exodus 31. Talmud Yerushalmi, Yoma 8, exempted activities necessary to save a person’s life even if they would otherwise be forbidden on Shabbat.