The Israelites followed Moses out of Egypt in an adrenaline rush. After years of being treated as sub-human disposable labor by the pharaoh and most Egyptians, they were free! Their Egyptian neighbors gave them gold, silver, jewels, clothes, swords—anything to make them leave so the plagues would end.1 Moses told his followers that God would give them the whole land of Canaan as their own country.2 They did not wonder what would happen to Canaan’s current inhabitants. All they had to do was follow God and God’s prophet, Moses, to happiness and glory.

An adrenaline rush does not last. Anxiety plagued the people along the way, because everything depended on God’s help. They panicked when God delayed in rescuing them from the Egyptian chariots at the Reed Sea,3 and they panicked whenever they were uncertain about food or water.4 When Moses disappeared into the fire on top of Mount Sinai for 40 days, they panicked so much that they made a golden calf for God to inhabit.5 Then God gave them an alternative, and they spent a contented year making a portable tent-sanctuary for God to dwell in.

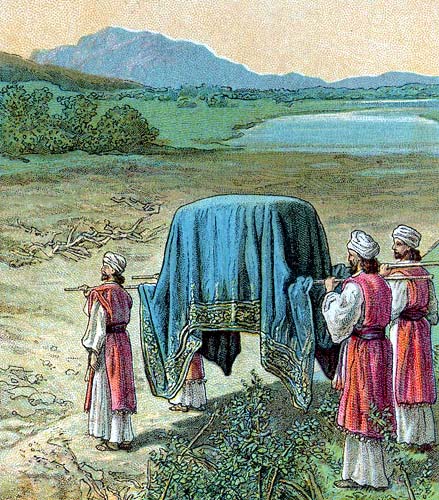

But once the new Tent of Meeting was completed and its new priests were ordained, it was time to leave Mount Sinai and head north toward Canaan.

Military service

When the book of Numbers opens, God tells Moses to take a census of men aged 20 and over—

“—everyone in Israel going out to war; you will muster them for their troops, you and Aaron.” (Numbers 1:2)

There is a separate census of the Levites, whose war duty is to guard the Tent of Meeting while the Israelites are encamped. Each Levite clan is assigned a campsite next to one side of the Tent, and the other twelve tribes must camp in a larger square around them. (There are twelve tribes not counting the tribe of Levi, because at this point the descendants of Joseph count as two tribes, Efrayim and Menashe.)

And God spoke to Moses and to Aaron, saying: “Each in its contingent, under the banner of their fathers’ house, the Israelites will camp, at a distance surrounding the Tent of Meeting they will camp. Those camping eastward, toward sunrise: the contingent of the camp of Judah, by their troops … (Numbers 2:1-3)

When they pull up stakes, they will travel in military formation, from Judah at the front to Naftali at the rear. (The Torah does not tell us where the women and children are in this army; we are left to assume they are walking with the men of their tribes.) And God will give the marching orders. This week’s Torah portion, Beha-alotkha, reminds us:

At God’s order the cloud would rise up from above the tent, and after that the Israelites would break camp; and in the place where the cloud would settle down, there the Israelites would camp. (Numbers 9:17)

But then we learn that the signal of the divine cloud is not enough; God also calls for two silver trumpets. When a priest blows a single short blast, the leaders of the Israelites must assemble at the Tent of Meeting for instructions. A longer, trilling blast means that that the people must march.

And when you enter into battle in your land with an attacker who attacks you, then the trumpets should cry out, and you will be remembered before God, your God, and you will be delivered from your enemies. (Numbers 10:9)

Thus when the Israelites finally leave Mount Sinai, they leave as an army expecting to fight for the land of Canaan.

Rebellion

They march north for three days, then camp in the Wilderness of Paran.

And the people became like bad complainers in the ears of God. God heard, and [God’s] nose heated up [with anger]. And a fire of God burned against them, and it ate up the outer edge of the camp. Then they wailed to Moses for help, and Moses prayed to God, and the fire sank down. (Numbers 11:1-3)

The book of Numbers does not tell us what the people are complaining about this time. According to Rashi, they felt sorry for themselves because they had walked for three days without stopping to camp, and they were weary.6 But according to Da-at Zekinim,

“The people were already mourning the potential casualties they would incur when going into battle against the Canaanites in order to conquer their land. They were lacking in faith and dreading warfare.”7

After the fire, people start complaining again.

Then the asafsuf who were among them felt a lusting lust. And moreover, the Israelites turned away and wept, and they said: “Who will feed us meat? We remember the fish that we ate in Egypt at no charge, the cucumbers and the melons and the leeks and the onions and the garlic! And now our nefesh is dry. There is nothing except for the manna before our eyes!” (Numbers 11:4-6)

asafsuf (אֲסְפְּסֻף) = rabble, riffraff; the non-Israelites who joined the exodus from Egypt. (They are called the eirev rav (עֵרֶב רַב)—the“mixed multitude”—in Exodus 12:38.)

nefesh (נֶפֶשׁ) =throat, appetite, life (in the sense of the animating force that makes one’s body alive).

First the asafsuf feel a lusting lust. Some commentators have written that they crave forbidden sexual relations; others that they lust for meat, and the Israelites pick up on their complaint. The manna that God provides every morning magically meets everyone’s nutritional needs, but not their emotional needs.

Their fond memories of some of the foods they ate in Egypt reveal that sometimes they wish they were still Pharaoh’s servants, instead of God’s. “… we are confronted by yearnings and nostalgia for a humdrum, small-time existence, a life of serfdom subject to their habits, passions and desires.” (Leibowitz)8

Life as God’s people seems too hard. In Egypt, they did not need to exercise any self-discipline, or follow so many rules. As long as they did whatever their foremen told them to, for as many hours as they were forced to work, they were fed “at no charge” and they could indulge in whatever pleasures they liked during their miniscule amounts of free time.

“The terrible price they had to pay for this give-away diet—slavery, suffering, persecution, murder of their children—is conveniently forgotten.” (Abravanel)9

Yet they lived at Mount Sinai for a year without complaining, the year when they were engaged in making the Tent of Meeting for God—a cooperative project calling for skilled craftsmanship. What has changed now, a three-day journey north of the mountain?

I would argue that now they are facing war, against unknown enemies. None of the Israelites were soldiers in Egypt. They engaged in only a single battle on their journey to Mount Sinai, when Amalek attacked them.10 The only other time anyone used the swords they took from Egypt was right after the golden calf worship, when Moses ordered the Levite men to go through the camp and kill the worst offenders.11

Yes, God rescued them many times on the way to Mount Sinai. But how could God make it easy to fight a long war against the Canaanites and seize all their land? They are not soldiers. How can they face all those battles? If God will no longer let them live quietly in the wilderness, they would rather be slaves in Egypt. Just thinking about the war ahead fills them with fear and dread. And they are close to the southern border of Canaan now. Desperate for a distraction and a respite from anxiety, the people long for comfort food.

We all live with anxiety about what will happen next. We might be afraid of an attack, or we might worry about our health, our work, our family, our country, our world. And most of us know about “good” strategies for managing anxiety and carrying on. I used to take long walks while singing prayers. These days, I find respite by studying and writing about Torah, and I fortify myself with naps, physical therapy, and nutritious food such as fish and leeks.

But when too many appointments and obligations use up my self-discipline, and I feel overwhelmed, I sit down with a pint of gelato. I crave sensual distraction. So I slowly savor every spoonful of gelato. Sometimes it takes a whole pint before I calm down.

I feel sorry for the people in this week’s Torah portion, who only have manna and memories.

- Exodus 11:1-3, 12:33-36 and 13:18.

- Exodus 6:2-8, 12:25, 13:5, 13:11

- Exodus 14:1-31.

- Exodus 15:22-25, 16:2-3, 17:1-7.

- Exodus 24:17-18, 32:1-6. See my post: Vayakheil & Ki Tisa: Second Chance.

- Rashi is the acronym of 11th-century rabbi Shlomoh ben Yitzchak.

- Da-at Zekinim, a 12th-13th century collection of commentary by tosafists, translation in www.sefaria.org.

- Nehama Leibowitz, Studies in Bamidbar (Numbers), translated by Aryeh Newman, The World Zionist Organization, Jerusalem, 1980, pp. 95.

- Yitzchak Abravanel, 15th century, quoted and translated in Leibowitz, p. 99.

- Exodus 17:8-13.

- Exodus 32:26-28.