The first animal offerings on the new altar are devoured by God’s fire—and so are two of the new high priest’s sons.

The new portable tent-sanctuary, also called the Tent of Meeting, is complete. The first five priests of the revised religion are dressed in their new vestments. Moses has sacrificed a “ram of ordination”; daubed its blood on Aaron, the new high priest, and his four sons; and splashed the rest of the blood on the new altar in front of the tent. After that, Aaron and his sons have spent seven days sitting in the entrance of the tent-sanctuary.

This week’s Torah portion, Shemini (Leviticus 9:1-11:47), opens on the eighth (“shemini”) day, when the high priest slaughters the animal offerings for the first time. Aaron applies the blood to the horns, base, and sides of the altar, and lays out the prescribed animal parts over the wood fuel inside.

Then Aaron lifted his hands toward the people and he blessed them. And he came down from doing the guilt-offering, the rising-offering, and the wholeness-offering. Then Moses and Aaron entered the Tent of Meeting. And they went out, and they blessed the people. (Leviticus 9:22-23)

The text does not say why Moses and Aaron pop into the Tent of Meeting and back out. One common answer in the commentary, as explained in the 17th-century commentary Siftei HaChamim, is:

“Since the incense is a service performed inside [the Tent of Meeting], Moshe could not teach Aharon during the seven days of installation, and he needed to teach him on the eighth day of the installation.”1

But it seems odd to interrupt the dramatic inauguration of the priests and the altar for a lesson on how to burn incense on the incense altar inside the tent—a job the high priest would not perform until sunset anyway.2

Another line of commentary theorizes that Moses and Aaron are waiting for God to make the next move. When nothing happens, they go inside God’s tent to pray. Perhaps they even say a prayer the back chamber, the Holy of Holies, where God promised to dwell in the empty space above the ark. According to Sifra, circa 300 C.E.:

“When Aaron saw that all the offerings had been sacrificed and all the services had been performed and the shekhinah had not descended upon Israel, he stood and grieved: “I know that the Lord is wroth with me [because of the Golden Calf].” … Whereupon Moses entered [the tent] with him, they implored mercy, and the shekhinah descended upon Israel.”3

The term shekhinah (שְׁכִינָה), meaning God’s presence dwelling in the world, was not invented until after the fall of the second temple in 70 C.E. The book of Leviticus says that after Moses and Aaron come out and bless the people, everyone sees God’s kavod emerge from the tent.

And the kavod of God appeared to all the people. And fire went out from in front of God, and it consumed the burnt offering and the fat parts on the altar. And all the people saw, and they shouted in joy and they threw themselves on their faces. (Leviticus 9:23-24)

kavod (כָּבוֹד) = glory, weight, magnificence, authority; (later) shekhinah.

If the divine fire starts “in front of God”, it apparently goes through the curtain screening off the Holy of Holies, through the main chamber of the tent, and out through the entrance curtain, without burning anything. Then God’s fire lands on the altar in front of the tent-sanctuary, and instantly creates a blaze that consumes the animal parts laid out there.

The people’s year of labor fabricating the Tent of Meeting has been crowned with success! No wonder they shout joyfully and prostrate themselves.

Meanwhile, Aaron’s two younger sons, Elazar and Itamar, are apparently just standing outside, waiting for instructions. But his two older sons, Nadav and Avihu, do something on their own initiative.

And Aaron’s sons Nadav and Avihu took, each one, his fire-pan. And he put embers in it, and he placed incense on it, and he brought it close before God—zarah fire, which [God] had not commanded them. (Leviticus 10:1)

zarah (זָרָה) = strange, foreign, unauthorized.

The commentary assumes that since Nadav and Avihu “brought it close before God”, they went inside the Tent of Meeting—as Moses and Aaron had done shortly before. Yet God’s instructions in Exodus are that incense for God is to be burned only on the gold incense altar in the main chamber of the sanctuary tent, and only by the high priest. Aaron must burn incense on the incense altar at sunset and sunrise, when he tends the lamps of the menorah. And he must burn the incense on embers brought in from the big altar outside. God adds:

“You may not bring up any zarah incense on it!” (Exodus 30: 9)

Nadav and Avihu, being only assistant priests, are not authorized to burn incense on the gold altar at all.

Moses and Aaron are allowed to go in and out of the Tent of Meeting, and to pray to God there, so they did not break any rules when they popped inside between blessings. But Nadav and Avihu violated God’s rules about incense: they used their own embers and their own fire-pans, and they usurped one of the high priest’s jobs. None of this was authorized, so their incense was zarah in three ways. Furthermore, they did not consult with their father or their uncle Moses first, to see if they had forgotten any rules that Moses had passed down from God.

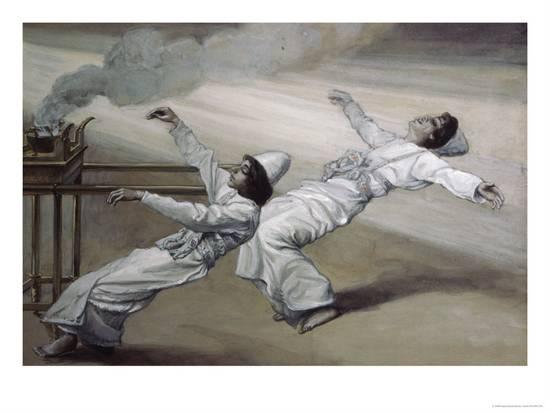

And fire went out from in front of God, and it consumed them; and they died in front of God. (Leviticus 10:2)

Why did they do it?

My favorite theory about why Nadav and Avihu risk death to bring unauthorized incense to God is that they are impulsive mystics. They are reckless because they are eager for the ecstasy of another close encounter with God, like their encounter partway up Mount Sinai when they and the 70 elders saw God’s feet on a sapphire pavement. (See my post: Shemini: Fire Meets Fire.)

But Jewish commentary offers other theories. This year, I am struck by the theory that God’s fire rushes out from the Holy of Holies only once, killing Nadav and Avihu on the way to igniting the animal parts on the altar.

One piece of evidence is that the two descriptions of God’s fire start with identical language in Hebrew. Here are direct English translations:

And fire went out from in front of God, and it consumed the burnt offering and the fat parts on the altar. (Leviticus 9:24)

And fire went out from in front of God, and it consumed them; and they died in front of God. (Leviticus 10:2)

Rashbam, a 12th-century commentator, explained the timing: “Fire came forth from before God—from the Holy of Holies … The fire found Aaron’s two sons there, near the golden [incense] altar, and it burned them to death. Then the fire went out of the Tabernacle to the copper altar where it consumed the burnt offering and the fats on the altar.”4

In this reading, Moses and Aaron have emerged from the Tent of Meeting and are outside blessing the people while Nadav and Avihu slip behind them and bring their own incense into the tent. God’s fire does not rush out of the tent until after the two assistant priests are inside.

Zornberg explained in her recent book, The Hidden Order of Intimacy: “Nadav and Avihu are on fire to bring God’s presence into their midst. Only in this way will the shadow of the Golden Calf be removed. This passion is pragmatic in its thrust: to resolve the suspense of waiting for the sacrifices to be consumed. It is, starkly, a passion to consummate the sacrificial rituals. The Netziv5 imagines the situation—the crowds of Israelites waiting for the revelation of the consuming fire: an element of social pressure plays its part.”6

Although God never promises to inaugurate the altar with divine fire, the crowd of Israelites is no doubt expecting to see something spectacular. It would be a disappointing anticlimax if the new priests had to light the first fire on the altar—the fire that is supposed to be so holy that it can never be allowed to go out.7 Naturally all the people are delighted when God’s miraculous fire rushes right through the entrance curtain of the tent-sanctuary and pounces on the altar.

All the people except Nadav and Avihu, who are dead because they disobeyed God’s rules at a critical time.

The book of Leviticus is primarily a priests’ handbook, listing rule after rule about how to correctly run a religion that no longer exists. The Israelite way of worship based on animal sacrifices died out quickly after the Romans destroyed the second temple in Jerusalem in 70 C.E. Since then, Jews have worshipped God through prayer, study, and good deeds. Few of the laws in Leviticus apply any more; the major exceptions are the rules for keeping kosher in Leviticus 11:1-23, and the ethical injunctions in the “Holiness Code”, Leviticus 19:1-35, which includes “Love your fellow as yourself” and “You must not place a stumbling-block in front of the blind”.8

Yet even when specific rules for worship no longer have any application, the concept of following the rules remains crucial. On a political level, the rule of law is necessary for civil society, and if the leader of a nation overrides it, everyone’s liberty is imperiled. On a religious level, each group has its own norms of behavior, and anyone who violates them too extravagantly will disrupt and perhaps even destroy a congregation. And on a personal level, we can function well in families and other social groups only when everyone observes basic rules of courtesy.

I believe it is good to question rules that may be outdated, and to suggest new rules to meet new needs. But human beings need rules. Without them, the best of us do unintended harm to others, and the worst of us get away with murder.

- Siftei HaChamim, 17th century, translation in www.sefaria.org.

- Exodus 30:7-8.

- Sifra, circa 300 C.E., translation in www.sefaria.org.

- Rashbam (12th-century Rabbi Shmuel ben Meir), translation in www.sefaria.org.

- The Netziv is the nickname of Naphtali Tzvi Yehudah Berlin, a 19th-century rabbi who wrote Ha-Amek Davar.

- Avivah Gottlieb Zornberg, The Hidden Order of Intimacy: Reflections on the Book of Leviticus, Schocken Books, New York, 2022, p. 98.

- Leviticus 6:12-13.

- See my posts: Kedoshim: Ethical Holiness, Kedoshim: Love Them Anyway, and Kedoshim: Vilification and Hindrance.