All ten times when a kiss occurs in the book of Genesis/Bereishit, a man is kissing one of his family members (but not his wife). The person kissed may embrace the kisser, and sometimes they both weep, but the Torah does not say that he or she kisses him back.

It is not unusual in the Hebrew Bible for someone to kiss a family member at a significant reunion (such as when Aharon kisses his brother Moshe after a long separation in Exodus 4:27), or at a formal final separation (such as when Naomi kisses her two daughters-in-law goodbye before she leaves Moab in Ruth 1:9).

In this week’s Torah portion, Vayishlach (Genesis 32:4-36:43), twin brothers Yaakov (“Jacob” in English) and Eisav (“Esau” in English) meet again after 20 years apart. Eisav kisses Yaakov, and both brothers weep.

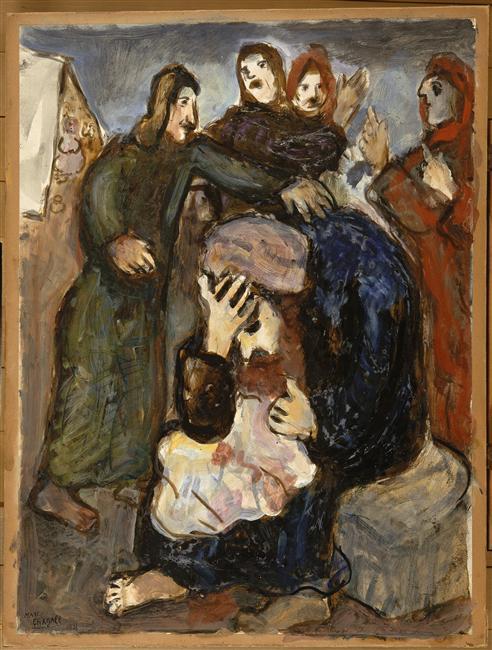

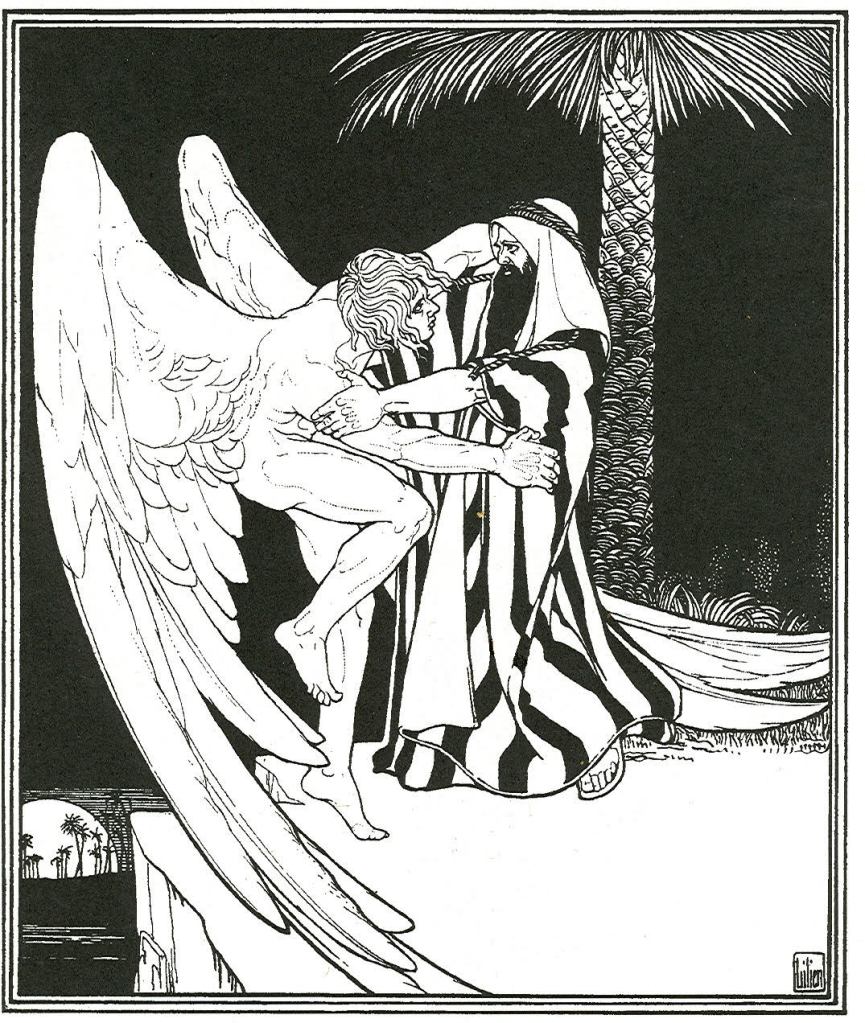

Then Eisav ran to meet him, and he embraced him, and he fell on his neck, vayishakeihu, and they wept. (Genesis 33:4)

vayishakeihu (וַיִּשָּׁקֵהוּ) = and he kissed him; or “and he was putting on armor”. (A form of nashak (נָשַׁק), the root of two different verbs that are homonyms. The root meaning “kiss” is the one that makes sense in context, since Eisav has just embraced his brother and fallen on his neck. Someone falls on someone else’s neck three times in Genesis, always at a tearful reunion between two male relatives.1 I imagine an embrace so close that the heads of the two men are pressed together and their cheeks touch.)

Yet even though it is a reunion between brothers, Yaakov does not expect the kiss.

Yaakov fled from Canaan 20 years earlier because Eisav, enraged because Yaakov had cheated him out of both an inheritance and a blessing,2 was planning to murder him as soon as their father died. During the years since then, Eisav left Canaan and founded his own kingdom, Edom, southeast of Canaan. And Yaakov acquired significant wealth in livestock while he lived in Charan, northeast of Canaan. Now that both men have been blessed with wealth, they no longer need an inheritance from their father.

Maybe Eisav no longer wants to kill his brother. But Yaakov is not so sure of that when he finally leaves Charan and heads back toward Canaan.

When he reaches the Yabok River with his large family, servants, herds, and flocks, Yaakov sends a message to Edom. His messenger returns with the news that Eisav is coming north to meet him, with 400 men—the standard size for a troop of soldiers. So Yaakov sends several generous gifts of livestock ahead to Eisav on the road, along with appeasing messages. (See my posts Vayishlach: A Partial Reconciliation and Vayishlach: Message Failure.) Finally Eisav and his men reach the Yabok River.

Yaakov raised his eyes and he saw—hey!—Eisav coming, and 400 men with him! (Genesis 33:1)

He organizes his wives and children so that his favorites are in the rear, where they will be the most likely to escape if Eisav’s men attack.

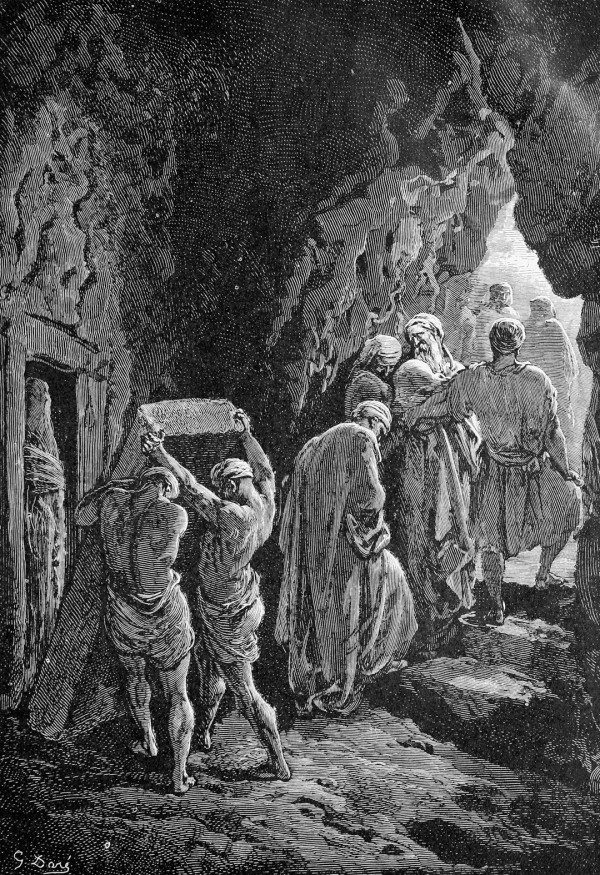

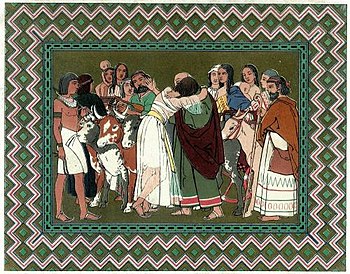

And he himself crossed over in front of them, and he bowed down to the earth seven times, until he came close to his brother. Then Eisav ran to meet him, and he embraced him, and he fell on his neck, vayishakeihu, and they wept. (Genesis 33:3-4)

What does Eisav’s kiss mean?

Extra dots

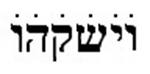

In Torah scrolls (which preserve every detail of how the words of Genesis through Deuteronomy have been written in scrolls since 500 C.E. or earlier) the word vayishakeihu looks like this:

By the 10th century C.E., the Masoretic system of “pointing” (nikudot)—putting various dots and short lines above, below, and inside Hebrew letters—had been universally adopted. These “points” add vowels, modify pronunciation, and indicate a few other distinctions that the letters alone do not reveal.3 Nikudot are still used for the complete Hebrew Bible when it is printed in book form, as well as some other Hebrew texts (but rarely in Modern Hebrew works).

In the Masoretic text, the word vayishakeihu in Genesis 33:4 appears with all the usual nikudot as well as the more ancient dots, sometimes called “extraordinary pointing”, above every letter:

This is the only place in the Hebrew Bible where any form of the verb nashak is written withdots that are not vowel points above the letters.

In fact, only fifteen verses in the whole Hebrew Bible contain a word with an extra dot above one or more letters.4 This “extraordinary pointing” was originally added by scribes who pre-dated the Masoretes, going back at least as far as the writers of the Dead Sea Scrolls (115-408 C.E.). The most common theory is that scribes used these dots indicate a problem with a word.

When I examined the verses with extraordinary pointing, I found three possible quibbles about grammar, two cases in which a repeated word might seem superfluous, and one weirdly spelled hapax legomenon. Seven other verses with extra dots use ordinary words with correct spelling and grammar, and no alternative meanings. Medieval midrash writers really stretched to come up with fanciful explanations for extraordinary pointing in these verses.5

That leaves two words with extra dots that may have a problem regarding the meaning of the word: lulei (לוּלֵא) in Psalm 27:13, and vayishakeihu (וַיִּשָּׁקֵהוּ) in Genesis 33:4.

I will save Psalm 27:13 for a future post. Now let’s look again at Eisav’s kiss.

Is Eisav’s kiss a problem?

Then Eisav ran to meet him, and he embraced him, and he fell on his neck, vayishakeihu, and they wept. (Genesis 33:4)

Perhaps some ancient scribes doubted that Eisav would kiss Yaakov, so they put extra dots over vayishakeihu to indicate that maybe the word should be erased from the verse altogether.

Alternatively, they might have put in the extra dots to indicate that vayishakeihu (וַיִּשָּׁקֵהוּ) is a misspelling, and the word should be vayishacheihu (וַיִּשָּׁכֵהוּ) = and he bit him; or “and he borrowed at interest”. (From nashakh (נָשַׁך), the root of two other verbs that are homonyms. It is at least possible for Eisav to bite his brother while they are embracing. No commentator would suggest that in between embracing Yaakov and bursting into tears, Eisav took time out to borrow money.)

Jewish commentary is divided among three opinions about Eisav’s kiss: that it is an expression of love or compassion; that it happens, but it is cold and grudging; and that it is really a bite.

Bereishit Rabbah, an early collection of midrash, includes two of these opinions:

“Rabbi Shimon ben Elazar said: … it teaches that at that moment he was overcome with mercy and he kissed him with all his heart. Rabbi Yannai said to him: If so, why is it dotted over it? Rather, it teaches that he did not come to kiss him, but rather to bite him, and Jacob’s neck was transformed into marble and the teeth of that wicked one were blunted. Why does the verse state: ‘And they wept’? It is, rather, that this one wept over his neck, and that one wept over his teeth.”6

Bachya ben Asher was one of the classic commentators who wrote that Eisav did kiss Yaakov, but it was not a loving kiss. “Here the reason they placed these dots was to let us know that this kiss was not whole-hearted. It was a kiss which originated in anger.”7

Eisav’s character

I think that the scribes who originally placed the extra dots over vayishkeihu accepted the symbolism that became widespread among rabbinic commentators around the 5th century C.E.: that Yaakov represents the Jews, and Eisav represents Rome and the Christians.8 These opposing symbols led to commentary painting Yaakov as all good, and Eisav as all evil.

The Torah itself uses wordplay to make Eisav a symbol for a long-standing enemy of the Israelites: the kingdom of Edom.9 Yet the stories about Eisav and Yaakov in Genesis are more nuanced. Before this week’s Torah portion, Yaakov has the admirable traits of intelligence, self-control, and adaptability; but he cheats his brother twice, first out of a selfish desire for more of the inheritance, then to please his domineering mother. Eisav is impulsive, over-emotional, and easily duped; but he goes to some trouble to cook treats for his blind father, and he does not make threats regarding his brother until after the second time Yaakov cheats him.

Twenty years after Yaakov fled to Charan, he is no longer concerned about inheriting from his father or pleasing his mother. He wants nothing from his brother except safe passage to Canaan for himself and his own people.

And Eisav? The way the Torah portrays him, I doubt he could maintain his rage over the stolen blessing for more than a week. He throws his energies into founding a new kingdom instead. I bet he is thrilled by the idea that he will be at the head of 400 men when he meets his sneaky, uppity brother again.

Of course he wants to be ready if Yaakov tries to pull any tricks on him. But when his brother showers him with gifts and compliments instead, Eisav is flattered. And when he sees Yaakov bowing down to him the way a subject bows to a king, his heart melts completely. Suddenly he loves Yaakov the way he probably did when they were children—when Yaakov, who was born only a minute after his twin, seemed much younger because he was smaller, less physically mature,10 and handicapped by the lower status of the second-born son.

Then Eisav ran to meet him, and he embraced him, and he fell on his neck, and he kissed him, and they wept. (Genesis 33:4)

- Genesis 33:4, 45:14, and 46:29.

- Genesis 25:29-34; Genesis 27:1-33. See my post Toledot: To Bless Someone.

- Many printed texts of the Hebrew Bible also include the trope marks invented by 10th-century Tiberian Masoretes to indicate how the words should be chanted. Here I exclude the trope for clarity.

- Genesis 16:5, 18:9, 19:33, 33:4, and 37:12; Numbers 3:39, 9:10, 21:30, and 29:15; Deuteronomy 29:28; 2 Samuel 19:20; Isaiah 44:9; Ezekiel 41:20 and 46:22; and Psalm 27:13.

- Midrash is a type of commentary that adds backstories and/or mystical meanings to the original text.

- Bereishit Rabbah 78:9, circa 300-500 C.E., translation in www.sefaria.org.

- Rabbeinu Bachya ben Asher, 1255–1340 C.E., www.sefaria.org.

- See Malka Z. Simkovitch, “Esau the Ancestor of Rome”, https://www.thetorah.com/article/esau-the-ancestor-of-rome.

- Genesis 25:26 (in which Eisav is born red—admoni, reminiscent of Edom, and hairy—sei-ar, like Mount Sei-ir in Edom); and Genesis 36:8 (which says “Eisav, he is Edom”).

- Eisav is born hairy (Genesis 25:26). When the twins are at least 40 years old, Yaakov reminds his mother: “My brother Eisav is a hairy man, and I am a smooth man.” (Genesis 27:11)