And Yaakov walked away from Beirsheva and went toward Charan. (Genesis/Bereishit 28:10)

So begins this week’s Torah portion, Vayeitzei (“And he went out”, Genesis 28:10-32:3). Yaakov (“Jacob” in English) has to leave home because his twin brother Eisav (“Esau” in English) has been threatening to kill him as soon as their ailing father dies.1

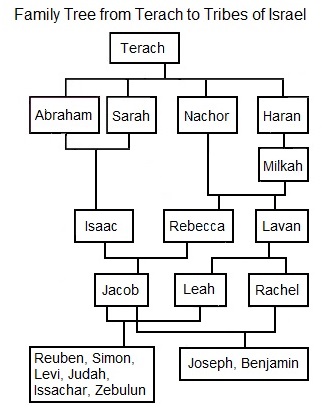

The family is dysfunctional. Eisav resents Yaakov for cheating him twice.2 Their parents, Yitzchak (“Isaac” in English) and Rivkah (“Rebecca” in English), play favorites, as last week’s Torah portion, Toledot, reports:

When the boys grew up, Eisav became a man who knew how to hunt, a man of the outdoors; and Yaakov was a quiet man staying indoors. And Yitzchak loved Eisav, because of [the taste of] game in his mouth; but Rivkah loved Yaakov. (Genesis 25:27-28)

Furthermore, Rivkah and Yitzchak are not frank with one another. Yitzchak does not tell his wife what he plans to do in terms of deathbed blessings for his sons. Rivkah manipulates Yaakov into deceiving his blind father and steal the blessing he plans to give Eisav. (See my post Toledot: Rebecca Gets It Wrong.) Everyone in the family assumes that Yitzchak has the power to pass on the blessing he received from God.

After Eisav threatens to kill Yaakov, Rivkah urges her favorite son to flee to Charan, where her brother lives, until Eisav’s anger has faded. Then she announces to her husband that she could not bear it if Yaakov, like Eisav, took a Canaanite wife. She does not need to say more; Yitzchak himself has never left Canaan, but he knows of one place outside the land: Charan, where his father Avraham and his wife Rivkah came from. So he orders Yitzchak to go there.

“… and take yourself a wife from there, from the daughters of Lavan, your mother’s brother” (Genesis 28:2).

Yaakov departs at once. He is over 40 years old, and this is the first time in his life he leaves his immediate family, and the land of Canaan.

Erecting a stone

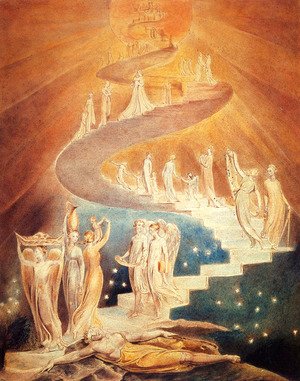

On the way to Charan he encounters God in a transformative dream. (See my post Vayeitzei: The Place.)

And Yaakov woke up from his sleep, and he said: “Truly there is God in this place, and I, I did not know!” And he was awestruck, and he said: “How awesome is this place! This is none other than a house of God, and this is the gate of the heavens!” And Yaakov got up early in the morning, and he took the stone that he had set by his head, and he set it up as a matzeivah, and he poured oil on top of it. (Genesis 28:16-18)

matzeivah(מַצֵּבָה) = a tall upright stone used for a religious purpose, as a grave marker, or as a memorial to an important event.

Erecting a tall stone and anointing it with olive oil was an accepted way of acknowledging a god in the Ancient Near East. Although Yaakov is smaller than his huge twin Eisav, he is strong enough to manhandle a long slab of stone.

Then Yaakov vows that if God takes care of him until he returns,

“… then Y-H-V-H will be my god. And this stone, which I have set up as a matzeivah, will become a house of God, and from everything that you give to me, I will tithe a tenth for you.” (Genesis 28:21-22).

The matzeivah remains at the spot as a witness to Yaakov’s experience and a marker for fulfilling his vow when he returns.

Rolling a stone

And Yaakov picked up his feet and went to the land of the Easterners. And he looked around, and hey! A well was in the field. And hey! There were three flocks of sheep lying down near it, because from that well they watered the flocks. And there was a large stone on the mouth of the well. For when all the flocks were gathered there, then they rolled the stone off from the mouth of the well, and watered the sheep, and brought the stone back to its place over the mouth of the well. (Genesis 28:1-3)

The shepherds could have chosen a lighter covering for their well, something made with wood that anyone could lift. But instead they use a stone that is so heavy, they have to cooperate to roll it off the well. This would prevent strangers or natives from drawing water unless a large group of men is there to enforce fair distribution of a limited resource.3 (Perhaps it takes all day for groundwater to seep in and refill the well.)

Yaakov greets the shepherds of the three flocks that have arrived so far, finds out they are from Charan, and asks about Lavan, whom they report is doing well. They add:

“And hey! His daughter Racheil is coming with the flock!” (Genesis 29:6)

As Racheil (“Rachel” in English) leads her flock over, Yaakov tells the men:

“Hey, the day is still long, it’s not time to gather in the livestock [for the night]. Water the sheep and go pasture them!” (Genesis 29:7)

Yaakov was in charge of the sheep in his father’s household, so he knows what should be done. But to me it seems bossy to tell men whom one has just met that they are wasting time. Perhaps Yaakov wants them to water their sheep and leave, so that he will have a moment alone with Racheil while she is watering her flock.

The shepherds tell Yaakov that they always wait until everyone is there to roll the stone off the mouth of the well.

He was still speaking with them when Racheil came with the sheep that were her father’s, for she was a shepherdess. And when Yaakov saw Racheil, a daughter of his mother’s brother Lavan, and the flock of his mother’s brother Lavan, then Yaakob stepped forward and rolled the stone off from the mouth of the well, and he watered the flock of his mother’s brother Lavan. (Genesis 29:10)

How does he have the strength to roll a stone so heavy that normally it can only be budged by many men working together? Tur HaArokh answered: “The new hope he had been given through his dream about the ladder had left its mark also on his body.”4

Another answer appears in Or HaChayim: “This teaches us that unless Jacob had had divine assistance he could not have moved that stone.”5

He might also have inherited strength and stamina from his mother. About 60 years earlier, when Rivkah was a teenager in Charan, she was at the well when a stranger arrived with a train of camels. She offered him a drink of water. Then she ran back and forth pouring heavy pitchers of water into the watering-trough until all ten of the stranger’s camels had drunk their fill. The stranger ( whom Avraham had sent to find a bride for his son Yitzchak) was awed by her athletic feat. (See my post Chayei Sarah: Seizing the Moment, Part 1.)

Rivkah’s son Yaakov also performs an athletic feat at the well, then waters Racheil’s sheep.

Then Yaakov kissed Racheil, and he lifted up his voice and wept. And he told Racheil that he was her father’s kinsman, and that he was Rivkah’s son. And she ran and told her father. And when Lavan heard tidings of Yaakov, his sister’s son, then he ran to meet him, and he embraced him and kissed him, and brought him into his house. (Genesis 29:11-13)

So far, so good. Yaakov, who never considered marriage while he was in Canaan, is smitten with Racheil. Now marrying into Lavan’s family is no longer just his parents’ idea. But although Lavan probably expects as large a bride-price as Avraham’s steward brought for Rivkah, Yaakov has unaccountably neglected to put any gold, silver, or jewelry in his pack. (See my post Vayeitzei: Guilty Conscience for one explanation.) So Yaakov offers to work for his uncle for seven years as the bride-price for marrying Racheil.

And Yaakov served seven years for Racheil, but they were like a few days in his eyes, because of his love for her. (Genesis 29:20)

Blocked by a stone

Traditional Jewish commentary often takes symbolism to extremes. Many classic commentaries identify the well near Charan with the temple in Jerusalem, and the three flocks of sheep with the three pilgrimage festivals there—even though Jerusalem and its festivals have nothing to do with Yaakov’s story. Others propose that the well represents knowledge of the Torah, and the stone is the evil inclination that blocks people from drinking it in. Compared to these far-fetched analogies, Robert Alter’s comment is refreshing:

“If, as seems entirely likely, the well in the foreign land is associated with fertility and the otherness of the female body to the bridegroom, it is especially fitting that this well should be blocked by a stone, as Rachel’s womb will be ‘shut up’ over long years of marriage.”6

But I am intrigued by a Chassidic commentary that identifies the well and the stone in terms that could be applied to Yaakov’s feelings by the end of the month during which he leaves home, encounters God, and falls in love—all for the first time.

Kedushat Levi compares the well to the human heart, which longs to connect with God, but is blocked as if by a stone. “The large stone is the evil urge … preventing the flow of God’s blessing. … He rolled the stone off the mouth of the well means that he removed the stumbling-block from the heart that flows with prophecy.”7

Arthur Green added: “… our evil urge, that which causes the human ego to assert its own will, blocks us from that vision. Our strongest force in defeating it is that of joy. When we open our hearts and rejoice … we overcome that need for self-assertion. Then divine blessing can flow upon us, even opening our hearts to the prophetic witness that is our true natural state of being.”8

While Yaakov is in Canaan, his “evil urge” is his jealousy of Eisav. Eisav is slated to get the larger inheritance of the firstborn son because he was born one minute before his twin brother. Furthermore, Eisav’s knack for hunting and cooking game wins their father’s love. So Yaakov cheats Eisav twice. He cannot let go of his jealousy until he is forced to leave Canaan, the inheritance, and Yitzchak. As soon as he is on the road, the heavy stone of Yaakov’s jealousy rolls away, and his heart opens. He has a vision and hears God in a dream, and the stone that lay by his head becomes his matzeivah for God. He falls in love with Racheil, and he rolls the stone off the well. Instead of continuing to dedicate his life to jealousy, Yaakov chooses a life of joy.

I always questioned the popular saying “Wherever you go, there you are”—with all the same problems you had before. It is true that we cannot erase the old experiences that shaped our personalities. Yet a big change in our lives can lead to psychological growth. Some of our old complexes can become healed scars instead of bleeding wounds, and we can move on.

In the portion Vayeitzei, Yaakov begins this process with the liberation of leaving home—leaving behind his manipulative mother, his detached father, and the unfair law of inheritance. Immediately he has stunning new experiences: encountering God, and falling in love. He changes. During the rest of his story in Genesis, he remains weighed down by mistrust and selfishness. But at least his jealousy and rivalry have rolled away, making a good life possible.

I, too, had a manipulative mother and a detached father, and I suffered from other types of unfairness when I was growing up. My liberation began when I escaped to college, and over many years the heavy stone rolled off my well. I still carry scars, but now love and a good life are not only possible for me, but a reality.

- Genesis 27:41.

- Genesis 27:34-36, referring to Genesis 25:29-34 and Genesis 27:5-27.

- According to 19th-century Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch, the heavy covering means that the people who live there do not trust one another.

- Rabbi Jacob ben Asher (c. 1269 – c. 1343), Tur HaArokh, translated in www.sefaria.org.

- Rabbi Chayim ben Moshe ibn Attar, Or HaChayim, 18th century, translated in www.sefaria.org.

- Robert Alter, The Hebrew Bible, Vol. 1, W.W. Norton & Co., New York, 2019, p. 103.

- Levi Yitshak of Berdyczow (1740-1809), Kedushat Levi, translated by Arthur Green,in Speaking Torah, Vol. 1, edited by Arthur Green, Jewish Lights Publishing, Woodstock, VT, 2013, pp. 126-127.

- Arthur Green, Speaking Torah, Vol. 1, p. 127.