Laughter is not always happy. In English we distinguish between the friendly act of laughing with someone and the cruel act of laughing at someone. A “fool” might be either a professional jester, or an innocent ignoramus who makes people laugh because of the contrast between his serious doings and what his words or actions mean to “normal” people. All of these meanings of “laugh” and “fool” are captured by Biblical Hebrew verbs based on the root tzachak, צָחֲק = laughed.

Abraham and Sarah laugh

The first person to laugh in the Torah is Abraham, when God tells him that he and his wife Sarah will finally have a baby the following year. His laughter is incredulous.

And Abraham fell on his face vayitzchak, and he said in his heart: Will he be born to a 100-year-old man, and will 90-year-old Sarah give birth? (Genesis 17:17)

vayitzchak (וַיִּצְחָק) = and he laughed.

The first six times a word derived from the root verb tzachak appears in the Torah, it is in the kal stem of the verb and refers simply to laughing. (See last week’s post, Vayeira: Laughter, Part 1.) Even the name of Abraham and Sarah’s son comes from the kal stem of tzachak.

“Truly Sarah, your wife, will be pregnant with your son, and you shall call his name Yitzchak, and I will establish my covenant with him …” (Genesis 17:19)

Yitzchak (יִצְחָק) = Isaac in English; “He laughs” in Hebrew.

When God reveals the same information to Sarah in last week’s Torah portion, Vayeira, she too laughs incredulously.

Lot the joker

Later in the portion Vayeira, Abraham’s nephew Lot tries to convince his sons-in-law that God is about to destroy the town of Sodom.

Lot went out and he spoke to his sons-in-law who had married his daughters, and he said: “Get up and go out from this place, because God is destroying the town!” But he was like a metzacheik in the eyes of his sons-in-law. (Genesis 19:14)

metzacheik (מְצַחֵק) = joking, amusing oneself, fooling around, making someone laugh; a jester, a fool.

Although metzacheik is derived from the same root verb as vayitzchak and yitzchak, it comes from the piel stem. While the kal stem of the root means laughing, the piel stem means making or causing laughter—and can also indicate someone who makes people laugh.

Lot’s sons-in-law see Lot as a fool who seriously believes something will happen that “normal” people know is impossible. How could the god of Lot and Abraham wipe out the whole town of Sodom? The men cannot believe in the miracle that kills them the next morning.

Abraham, standing on the heights above, sees Sodom and Gomorrah being obliterated, and moves his household south, settling near Gerar.

Embarrassing laughter

Then Sarah became pregnant, and she bore for Abraham a son for his old age, at the appointed time that God had spoken of … And Abraham was 100 years old when his son Yitzchak was born to him. And Sarah said: God has made tzechok for me; everyone who hears, yitzachak about me. (Genesis 21:2, 6)

tzechok (צְחֹק) = laughter (noun, from the root tzachak).

yitzachak (יִצֲחַק) = he will joke, he will amuse himself or others (from the root tzachak in the piel stem).

For Sarah, having a baby is a good miracle. After all, in the Torah portion Lekh-Lekha she wants a son and heir so much that she gives Abraham her slave Hagar and plans to adopt their baby, Ishmael. That plan does not go well, but now Sarah has her own son.

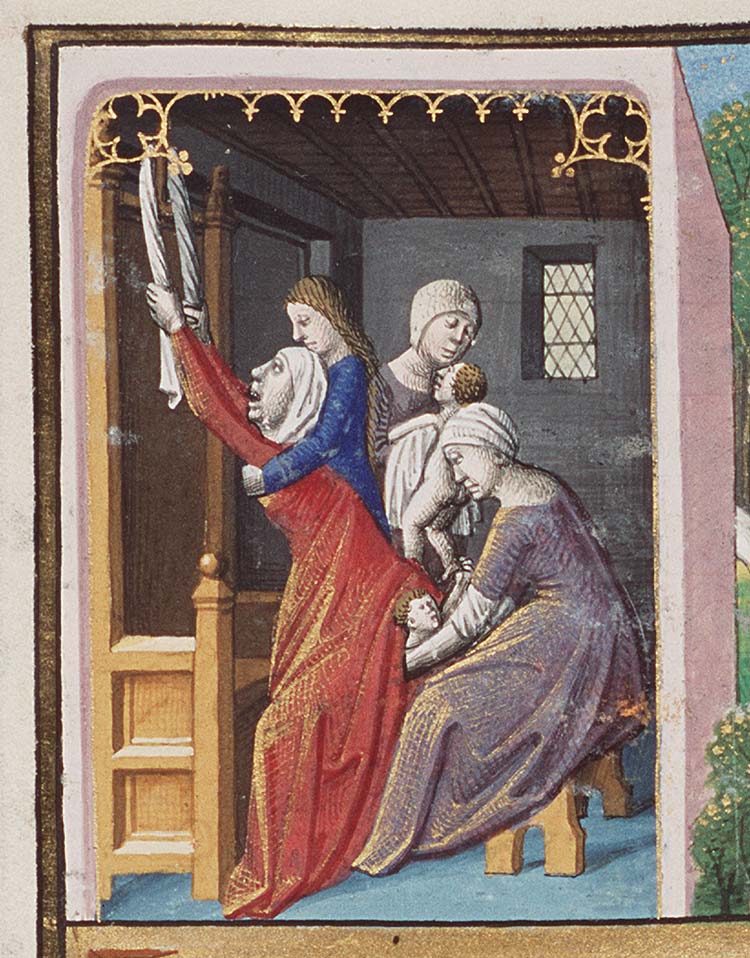

However, instead of laughing with joy, Sarah is self-conscious about the laughter she expects from other people. How ridiculous it looks for a 90-year-old woman to nurse an infant! Sarah expects to be the butt of jokes.

Yishmael the joker

When Yitzchak is weaned, Abraham holds a feast in celebration. There Sarah observes Ishmael, now an adolescent, doing something that alarms her.

Sarah saw the son of Hagar the Egyptian, whom she had born to Abraham, metzacheik. And she said to Abraham: Drive out this slave-woman with her son, because the son of this slave-woman must not inherit along with my son, with Yitzchak! (Genesis 21:9-10)

Sarah observes Ishmael metzacheik: “joking, playing, amusing himself”. But what, exactly, is the boy doing?

Rashi1 suggested three possibilities taken from the Midrash Rabbah on Genesis2: Sarah might have seen Ishmael in the act of sexual immorality, idolatry, or killing people in a contest. His bad moral character would give Sarah an excuse to exile him, so that her own Yitzchak would become Abraham’s only heir.

Ramban and later Sforno3 wrote that Ishmael is joking that Yitzchak is actually the son of Avimelekh, the king of Gerar, who only pretended he had not touched Sarah when he held her captive in chapter 20. This is a potentially profitable joke for Ishmael to make; if Yitzchak really were the son of Sarah and Avimelekh, then Ishmael would be the only son of Abraham, and therefore his only heir.

Robert Alter has pointed out that since Yitzchak and metzacheik come from the same root, “we may also be invited to construe it as ‘Isaacing it’—that is, Sarah sees Ishmael presuming to play the role of Isaac, child of laughter, presuming to be the legitimate heir.”5

If Ishmael were merely laughing with Yitzchak, his behavior might be innocent. But since the text says she sees Ishmael metzacheik, making someone laugh, he probably is joking around at Yitzchak’s expense.

Yitzchak plays

What about Yitzchak himself? Is he named “He laughs” merely because Abraham laughs at the news of his conception?

The Torah never says that Yitzchak himself laughs. But in next week’s Torah portion, Toledot, Yitzchak creates laugher (in the piel stem).

Yitzchak and his beloved wife Rebecca move to Gerar to escape a drought, and Yitzchak, like his father Abraham, worries that the king of Gerar or one of his men will seize Rebecca for his own harem. If the men of Gerar know she is married to Yitzchak, he thinks, they will kill him so they can take her as a widow without fear of reprisal. Thus Yitzchak, like Abraham, calls his wife his sister. (See my post Lekh-Lekha, Vayeira, & Toledot: The Wife/Sister Trick.)

But unlike his father, Yitzchak cannot keep his hands off his wife.

And the days became long for him there. And Avimelekh, the king of the Philistines, looked down through the window, and he saw—hey!—Yitzchak metzacheik with Rebecca, his wife! (Genesis 26:8)

Here metzacheik means fondling: playing or fooling around sexually. There is no implication of mockery or meanness in Yitzchak’s behavior. He is merely in love with his own wife, and touches her when he thinks they are unobserved.

Like the king of Gerar who took in Sarah, this king of Gerar is horrified to discover that an apparently single woman is actually someone’s wife. The king issues an order: Anyone who touches this man or his wife shall certainly die. (Genesis 26:11) And Yitzchak prospers in Gerar.

Yitzchak, “He laughs”, is surrounded by people who laugh and joke. Both his parents laugh at the incredible mismatch between their extreme old age and having a baby. Both accept God’s miracle and adjust their lives to it, Abraham by winning God’s reassurance that his older son Ishmael will survive, and Sarah by finding a reason to exile Ishmael and give her own son the inheritance.

Yitzchak’s uncle Lot informs his sons-in-law of a different divine miracle, the impending destruction of Sodom. His earnest belief in something they think is impossible makes them laugh, and they see him as a fool, a metzacheik. So they stay put in Sodom, and are annihilated.

May we become more like Abraham and Sarah than like Lot’s sons-in-law: flexible and able to accept the unexpected in our lives.

When Ishmael is metzacheik at Yitzchak’s weaning feast, he is probably making other people laugh at Yitzchak’s expense. But when Yitzchak is metzacheik with his wife in Gerar, he is probably making her laugh with his playful fondling as he expresses his love for her.

May we become more like Yitzchak than like Ishmael; may we guard ourselves against cruelty, even toward our opponents, when we joke around, and restrict ourselves to generating only loving laughter.

- Rashi is the acronym for the 11th-century C.E. French rabbi Shlomoh Yitzchaki, who wrote commentary on the entire Hebrew Bible and all of the Babylonian Talmud.

- Genesis/Bereishit Midrash Rabbah is a compilation of commentary by rabbis of the first through third century C.E. The three alternatives on page 53:11 are based on the use of similar words in three other passages. In Genesis 39:17, the verb letzachek (לְצַחֶק, in the piel) is used to accuse someone of attempting sexual seduction. In Exodus 32:6, letzacheik (לְצַחֵק, in the piel) is what the Israelites do after sacrificing to the Golden Calf. In 2 Samuel 2:14, the lietwort viysachaku (וִישַׂחַקוּ) is used to mean a tournament or contest in which pairs of soldiers fight to the death.

- Ramban is the acronym for the 13th-century C.E. rabbi Moshe ben Nachman Girondi, a.k.a. Nachmanides. 16h-century C.E. rabbi Ovadiah Sforno gave the same opinion.

- Rachel Adelman, “The Expulsion of Ishmael: Who Is Being Tried?”, thetorah.com.

- Robert Alter, The Five Books of Moses, W.W. Norton & Co., New York, 2004, p. 103.