The first three covenants God makes with human beings in the Torah are unconditional; God promises to do something regardless of what the other party does. First God says to Noah:

Everything on earth will perish, but I will raise up my berit with you, and you shall come into the ark… (Genesis/Bereishit 6:18)

berit (בְּרִית) = covenant, pact, treaty of alliance. (This is the source of the Yiddish word bris = covenant of circumcision.)

After the flood, God tells Noah and his descendants not to eat the blood in animal meat, and not to shed the blood of humans. But then God declares a unilateral covenant with all future humans and animals on earth—without making it contingent on humans following the rules about blood.

And I, here I am, raising up my berit with you and with your descendants after you, and with every living creature that is with you—with birds, with beasts, and with everything living on the earth with you …I raise up my berit with you, and I will not cut off all flesh again by the waters of the flood, and never again will there be a flood to destroy the earth. (Genesis 9:9-11)

God makes a third, and last, unconditional covenant in this week’s Torah portion, Lekh-lekha (“Get yourself going!”).

Abraham hears God’s call at age 75, leaves his home in Aram, and travels to Canaan, where he is landless and childless (though he has a wife, a nephew, and a large number of men working for him). God promises Abraham three times that he will have a whole nation of descendants, from his own loins, and they will possess the land of Canaan.

The third time, Abraham points out that he is still childless. God shows him the stars, and says his descendants will be just as numerous. The sight of the stars moves Abraham, and he trusts God on this. Then God repeats that Abraham will possess the land of Canaan, and Abraham questions God again:

“God, my master, how will I know that I will take possession of it?” (Genesis 15:8)

God responds by changing the promise into a covenant. And since words alone do not seem to be enough for Abraham any more, God does not just “raise up” or establish a covenant through words, but “cuts” a covenant in a ritual used for centuries among ancient people in the Middle East, including Akkadians, Amorites, Hittites, Assyrians, and Arameans as well as Israelites.

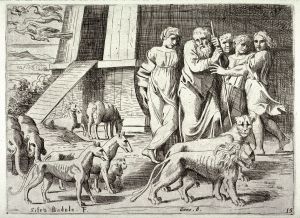

In this ritual, two parties ratified a pact or treaty by slaughtering one or more animals and cutting each one in half. Surviving written documents include threats that if one of the parties does not uphold the agreement, he will be cut in half like the animal.

At some point, Israelites added a step to the ritual: after an animal was cut in two, someone walked between the pieces.

…the berit that they cut before Me: the calf that they cut in two and they passed between its pieces: the officers of Judah, and the officers of Jerusalem, the court officials, and the priests, and all the people of the land, the ones who passed between the pieces of the calf … (Jeremiah 34:18-19)

In this week’s Torah portion, God requests five animals, from the five species that are used later in the Torah for burnt offerings.

“Take for me a three-year-old heifer and a three-year-old she-goat and a three-year-old ram and a turtledove and a young pigeon.” And he took for [God] all these, and he cut them through the middle, and set each part opposite its fellow. But the birds he did not cut. (Genesis 15:9-10)

The 20th-century rabbi Meir Zlotowitz claimed that Abraham placed the two uncut birds opposite one another, completing the path between the pieces. And God grants him a vision.

And the sun had set, and darkness happened, and hey!—a smoking tanur and a torch of fire, which passed between these cut pieces. On that day, God cut with Abraham a berit, saying: To your descendants I have given this land, from the river of Egypt up to the great river, the river Euphrates. (Genesis 15:17-18)

tanur (תַנּוּר) = fire-pot, oven; brazier, furnace.

In the books of Exodus and Deuteronomy, God’s presence is often described in terms of smoke and fire. But imagine a disembodied smudge-pot and a torch passing between the pieces!

This is God’s last unilateral covenant in the Hebrew Bible. The next covenant between God and Abraham, at the end of this week’s Torah portion, is conditional; God will multiply Abraham’s descendants if and only if every male in Abraham’s household is circumcised.

After that, covenants between God and humans are like Biblical covenants between two humans: the party with more power promises to protect the party with less power, on the condition that the weaker party remains loyal to his superior and follows the stipulated rules. In God’s case, people must obey various laws, observe holy days, and/or refrain from worshiping other gods as a condition for God’s favor and protection.

Why does God switch to conditional covenants? I think God is frustrated by what happens right after God cuts a covenant with Abraham. His post-menopausal wife, Sarah, gives him her slave Hagar to produce a son for him; and instead of continuing to wait for a miraculous birth, Abraham cooperates. But God seems disappointed, and makes a new covenant with Abraham. Besides requiring circumcision as a condition, God specifies that Sarah must be the mother of the son who inherits the covenant, and says: I will bless her, and also give you a son from her. (Genesis 17:16)

From then on, God apparently does not trust humans to make their own arrangements without at least a few divine rules to guide them.

Today people make many conditional contracts with each other: for rent, for employment, for services. Some people also try to bargain with God, promising to do something they think God wants in exchange for a divine favor—as if God could be bribed.

There is also a widespread unconditional covenant between human beings today: marriage. Our wedding rituals can be elaborate (though they do not feature cutting up animals and walking between the pieces). But at the heart of the ceremony, each person promises to be with and support the other (like God promising to favor and protect someone), regardless of what happens.

Today, Jewish circumcision is more like an unconditional covenant with God. Infant boys are dedicated to the God of Israel through circumcision with no expectation that God will grant them fertility or any special favors in return.

But can you imagine God initiating a covenant with a human being today? Can you imagine God raising up or cutting a covenant with you? What would it be like?

Has it already happened, in some subtle way?