(This is my ninth post in a series about the conversations between Moses and God, and how their relationship evolves in the book of Exodus/Shemot. If you would like to read one of my posts about this week’s Torah portion, Vayakheil, you might try: Vayakheil & Psalm 13: Waiting in Contentment.)

Between God and Moses’ conversation at the burning bush on Mount Sinai and God’s revelation to all the Israelites at the same mountain a couple of years later, the God-character in Exodus maintains the same approach to Moses: calm, reassuring, patient with all of his prophet’s panic and dithering, but always nudging him to take the next step toward becoming the human leader of the Israelites.

By the time Moses returns to Mount Sinai, he has become that leader. His experiences have changed him from a frightened introvert with an inferiority complex who is certain he cannot speak convincingly or lead anyone (see my posts Shemot: Not a Man of Words and Shemot: Moses Gives Up) into someone who asks God for advice, but is prepared to speak and to make decisions for his people when necessary (see my post Beshalach: Moses Graduates). While God remains the ultimate authority, Moses is the human leader whom the Israelites both follow and complain to.

Now that the Israelites have camped at the foot of God’s mountain, they must make a binding covenant with God. Moses, knowing he must arrange it, orchestrates four covenants in a row.

First covenant

One the Israelites have pitched camp, Moses climbs up the mountain to speak with God—even though he had no trouble speaking with God at any place in Egypt or on the journey across the wilderness. Perhaps at Mount Sinai, he keeps hiking up and down so that all the Israelites can see him when goes to speak with God. (See my post Yitro: Moses as Middle Manager.) The first time he walks back down,

Moses came and summoned the elders of the people, and he set before them all these words that God had commanded him. And all the people answered as one, and they said: “Everything that God has spoken, we will do!” Then Moses brought the words of the people back to God. (Exodus 19:7-8)

This is the first covenant, an oral agreement. “All these words that God had commanded him” are only that the people must “really listen to my voice and observe my covenant” and become “a kingdom of priests, a holy nation”. In return, God promises that the Israelites will be God’s personal treasure out of all the nations on earth.1

This initial agreement may be inspiring, but it lacks specifics.

Second covenant

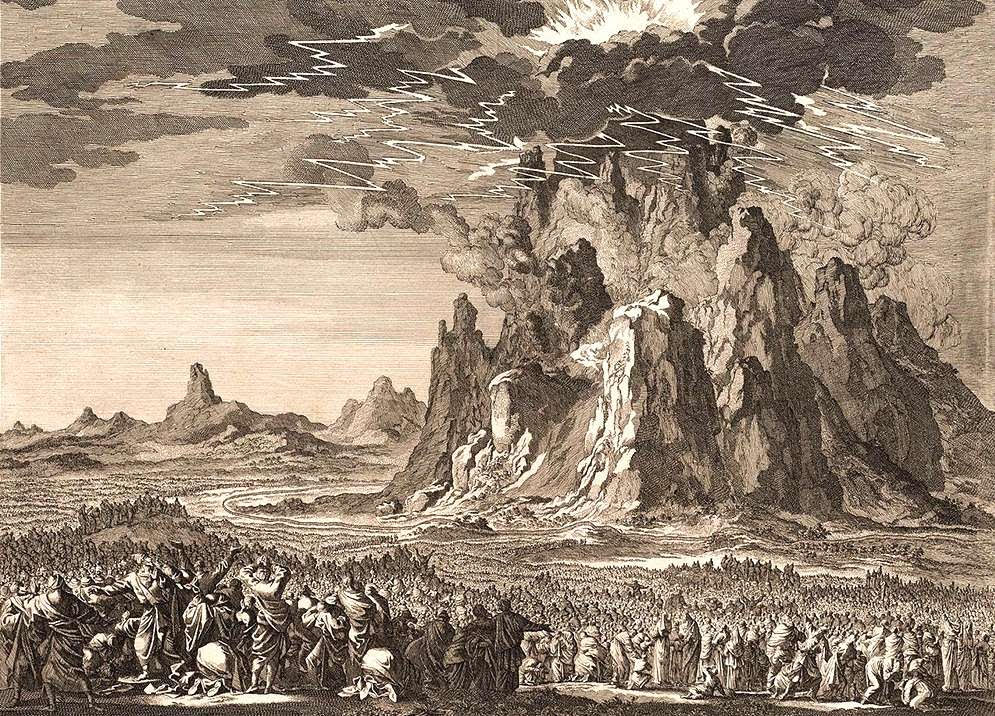

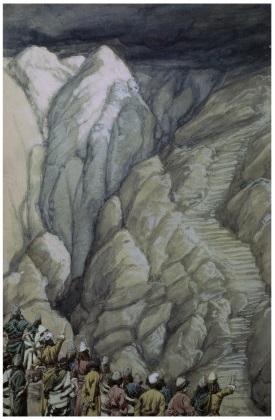

Three days later, God stages what Jews call “The Revelation”, which includes dense cloud, thunder, lightning, the sound of a ram’s horn blowing, smoke, and earthquake.2 Moses leads the people out of the camp to the foot of the mountain.

And God came down upon Mount Sinai, to the top of the mountain. And God summoned Moses to the top of the mountain, and Moses went up. (Exodus 19:20)

Moses obeys even though Mount Sinai seems to be an erupting volcano. Clearly he has learned to trust God to preserve his life.

Before the revelation begins, God tells Moses:

“Hey, I myself am coming to you in a dark cloud, so that the people will listen when I speak with you, and also they will trust you forever.” (Exodus 19:9)

We do not know whether the dark cloud is the smoke emerging from the mountain, or a manifestation of God coming down from the heavens.

At this point, the redactor of the story inserts what have become known as the Ten Commandments (called “The Ten Words” when they are repeated in Deuteronomy).3 Then God’s revelation continues with:

And all the people were seeing4 the sounds of thunder and the flashing lights and the sound of the ram’s horn and the smoking mountain. And the people saw, and they trembled, and they stood at a distance. And they said to Moses: “You speak with us, and we will listen! But may God not speak with us, lest we die!”5 (Exodus 20:15-16)

God’s plan is working; the people are terrified of God—and they now trust Moses and promise to listen to whatever he says God said.

Moses steps closer to the dark cloud where God is, and God tells him the dozens of laws in verses 20:21 through 23:22, which are more specific than the “Ten Commandments”. Most of the laws are ethical rules for an agrarian society, including two laws about not oppressing an imigrant.6

Then comes God’s side of the covenant:

“And you must serve God, your God! And [God] will bless your food and your water, and I will remove sickness from among you. There will be no miscarriage or barrenness in your land, and the number of your days I will make full. My terror I will send before you, and I will panic all the people among whom you come, and I will give all your enemies to you by the neck.” (Exodus 23:25-27)

The ancient Israelites prized fertility as well as good health and long life. And people facing a protracted war for land ownership would be relieved to learn that God will be on their side—as long as they follow the rules.

The final word from God during this session with Moses is about the Canaanite tribes that have been living for centuries in the land God will give to the Israelites:

“You must not cut a covenant with them or their gods. They must not dwell in your land, lest they cause you to do wrong against me.” (Exodus 23:32-33)

Immigrants should be treated fairly, but existing residents of Canaan must be rejected.

Then God tells Moses:

“Come up to God, you and Aaron, Nadav and Avihu, and seventy elders of Israel, and bow down from a distance. Then Moses alone will come close to God, but they must not come close, and the people must not go up with him.” (Exodus 24:1-2)

But first, without any order from God, Moses confirms a second oral covenant between God and the people.

Then Moses came and recounted to the people all the words of God and all the laws. And all the people answered with one voice, and said: “All the words that God has spoken, we will do!” (Exodus 24:3)

Third covenant

Next on God’s agenda is a special revelation and covenant partway up Mount Sinai, between God and seventy elders plus Aaron and his two older sons. But Moses has a different idea. He imagines a written covenant, which he will notarize with ritual elements that the Israelites are accustomed to: an animal sacrifice and the splashing of its blood. And God does not interfere with Moses’ plan.

Then Moses wrote down all the words of God. And he started early in the morning and he built an altar below the mountain, and twelve standing-stones for the twelve tribes of Israel. And he sent the young men of the Israelites, and they made rising offerings and slaughtered wholeness offerings for God: bulls. And Moses took half the blood and put it in bowls, and half the blood he threw over the altar. (Exodus 24:2-6)

The altar represents God in this covenant ceremony, so Moses scatters half of the blood over it. He reserved the other half for the Israelites after they have agreed to the covenant.

Then he took the scroll of the covenant, and read it in the hearing of the people. And they said: “Everything that God has spoken, we will do and nishma!” (Exodus 24:4-7)

nishma (נִשְׁמָע) = we will listen, hear, pay attention, heed, obey.

This time the people add another vow after “we will do”. Why do they add nishma? According to one early commentary, their vow should be translated as “We will do, and then we will understand.”7 The people were wise enough to realize that sometimes you cannot understand what an action means until after you have done it.

Another explanation is that the Israelites meant: “We will carry out what God has said already, and we are also prepared to listen (obey) to what He will command from here on in.”8

Either way, the people make a stronger commitment (although they break it when they worship the golden calf). And Moses figured out how to inspire them to make that commitment.

Then Moses took the blood and threw it on the people, and he said: “Here! The blood of the covenant that God cut with you according to all these words!”9 (Exodus 24:8)

Only after the Israelites as a whole have finished ratifying the written covenant with God does Moses carry out God’s order regarding the seventy elders.

Fourth covenant

Then went up, Moshe and Aharon, Nadav and Avihu, and seventy of the elders of Israel. And they saw the God of Israel, and under [God’s] feet something like a brick pavement of sapphire, and like the substance of the heavens for purity. And God did not send out [God’s] hand to the eminent Israelites. Vayechezu God, and they ate and they drank. (Exodus 24:10-11)

vayechezu (וַיֶּחֱזוּ) = and they beheld, saw in a vision, perceived.

This may not sound like a covenant between God and the elders. Furthermore, many medieval Jewish commentators criticized the Nadav, Avihu, and the elders for eating and drinking at a time like that.10 Others wrote that looking at God “provided them with the kind of satisfaction ordinary people get through the intake of food and drink”.11

But one 13th-century commentary pointed out: “…we know from Avraham, Yitzchok and Yaakov, that when they made a pact with human beings, they invariably sealed it by having a festive meal with their partner.”12

Rabbi Steinsaltz wrote in his 2019 commentary: “And they beheld God, to the extent that this is possible, and ate the peace offerings and drank, as though sharing a meal with God.”13

Moses walks to the top of a smoking, thundering volcano because he trusts God to keep him safe. And God goes along with Moses’ additional covenant ritual because he trusts Moses to know what the Israelites need. The two leaders have reached a point of harmony.

Until God decides to test Moses, and Moses decides to test God.

To be continued …

- See my post: Yitro: Moses as Middle Manager.

- Exodus 19:16-20; Deuteronomy 4:13.

- Exodus 20:1-14.

- Exodus 20:15 says “the people ro-im (רֺאִים)” sounds as well as sights. Usually ro-im means “were seeing”. Some translations say “the people were perceiving”. Others suggest that the people were experiencing synesthesia.

- The story assumes that Moses could hear the people below when he was on top of the mountain. Perhaps the authors imagined a shorter mountain than any of the current top candidates for Mount Sinai: Jabal Sin Bisher, Jabal Musa, and Chashem el Tarif.

- Exodus 22:20, 23:9. The word geir (גֵר) is often translated as “stranger”, but it means a resident alien or immigrant.

- Avot DeRabbi Natan 22:1, c.700–900 CE, translation in www.sefaria.org.

- Rashbam (12th century Rabbi Shmuel ben Meier), translation in www.sefaria.org.

- The story assumes that enough of the thousands of Israelites were splashed with blood to make the ritual effective.

- From Rashi (11th century) to Rabbeinu Bachya (14th century).

- Chayim in Attar, Or HaChayim, 18th century, translation in www.sefaria.org. This concept also appears in Talmud Bavli, Berakhot 17a.

- Chizkuni, 13th ccentury, translation in www.sefaria.org.

- Rabbi Adin Even-Israel Steinsaltz, The Steinsaltz Tanakh, Koren Publishers, Jerusalem, 2019, quoted in www.sefaria.org.