A 2,000-year-old tradition pairs every weekly Torah portion with a haftarah, a reading from the Prophets/Neviim. In this week’s Torah reading, Terumah (“Donations”), God gives Moses instructions for building a sanctuary. This week’s haftarah is a passage from the first book of Kings about how King Solomon begins building the temple in Jerusalem.

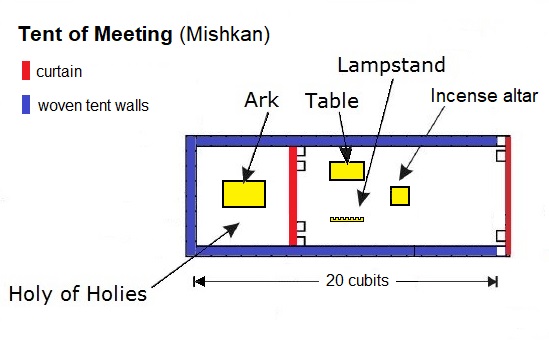

The sanctuary and the temple both contain the ark, menorah, bread table, and incense altar. Both are places where priests perform the rituals prescribed in the Torah. But there are dramatic differences between the two structures.

For one thing, the building materials dictate whether each holy structure is portable or stationary. The Torah portion Terumah specifies that the walls of the mishkan will be made out of woven pieces of cloth hung on a framework of gilded acacia planks and beams.

And you shall make the mishkan of ten panels of fabric, made of fine twisted linen, and sky-blue dye and red-violet dye and scarlet dye …(Exodus/Shemot 26:1)

mishkan (מִשְׁכָּן) = sanctuary, dwelling-place for God. (The word is used for the portable tent-like sanctuary created in the book of Exodus and used until the second book of Samuel.)

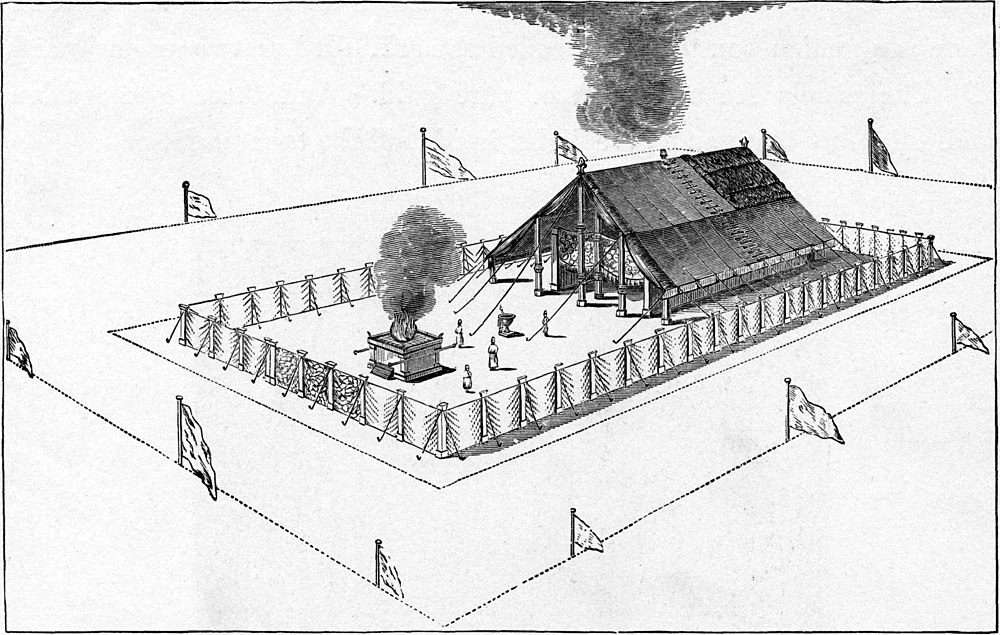

Next God tells Moses to make the roof out of woven goat-hair, and cover it with tanned hides. The mishkan would look like a huge tent of vividly-colored cloth, its framework resting directly on the earth. After it has been built, the Torah often calls this sanctuary the “Tent of Appointed Meeting”.

The courtyard in front of it, containing the altar for burning animal offerings, is to be enclosed by another wall of linen cloth, this one roofless. I can imagine the cloth walls of both the courtyard and the tent glowing in the sunlight, and the gold, silver, and bronze fittings gleaming. The structure would be beautiful, but also obviously portable, easy to disassemble and move to the next location.

While the mishkan is temporary, Solomon’s temple is built to last.

The king commanded, and they quarried huge stones, valuable stones, to lay the foundation of the house with hewn stones. (1 Kings 5:31)

On this foundation, the “house” is built out of more large squared stones, then paneled inside with cedar wood, and roofed with cedar planks. Additional rooms are built against the outside walls, all the way around. The temple is three stories high, with stairs and narrow latticed windows. This sanctuary could never be disassembled and moved. It is supposed to be permanent. According to the Hebrew bible, it lasted for four centuries, until the Babylonian invaders destroyed it. During that time, the central place of worship for the southern kingdom remained fixed in its capital, Jerusalem.

Another important difference between the tent and the temple is how the materials and labor to build them were obtained. The materials for the tent—textiles, hides, wood, and metals—are all gifts volunteered by the Israelites. This week’s Torah portion opens with God asking for only voluntary donations.

God spoke to Moses, saying: Speak to the children of Israel, and they shall take for me a donation from every man whose heart urges him; [from him] you shall take My donation. And this is the donation that you shall take from them: gold or silver or bronze, or sky-blue or red-violet or scarlet dyes, or linen or goat hair, or hides… (Exodus/Shemot 25:1-5)

But the stone and cedar for Solomon’s temple are purchased from a foreign king, Chiram of Lebanon. This week’s haftarah opens:

God had given wisdom to Solomon, as [God] promised him; and there was peace between Chiram and Solomon, and the two of them cut a treaty. (1 Kings/Malchim 5:26)

Just before this verse, the first book of Kings describes the deal between Chiram and Solomon: Hiram will provide timber and stone for Jerusalem, and in exchange Solomon will pay Hiram in annual shipments of wheat and olive oil—shipments that would require a heavy tax on Israel’s farmers.

In the book of Exodus, both women and men enthusiastically volunteer to do the weaving, carpentry, and metal-working for the tent sanctuary. In the first book of Kings, Solomon imposes forced labor on the Israelite men to do the logging and quarrying.

And King Solomon raised a mas from all of Israel, and the mas was 30,000 men. He sent them to Lebanon, 10,000 a month in turns; they were in Lebanon for a month, two months at home. And Solomon loaned 70,000 burden-carriers and 80,000 stone-cutters on the mountain. (1 Kings 5:28-29)

mas (מַס) = compulsory labor, corvée labor, levy

Compulsory labor, mas, is what the pharaoh imposed on the Israelites in Egypt—the slavery that God and Moses freed them from. King Solomon gets away with his temporary mas, but later in Kings, his son Rechavam imposes an even heavier “yoke” on his people, and they revolt against him.

So while the mishkan is constructed with voluntary gifts and voluntary labor, the temple is built through agricultural taxes and forced labor.

In the Torah portion, Moses gets instructions for making a sanctuary from God Itself. In the haftarah, Solomon remembers his father David’s desire to build a temple, and after he has built a palace for himself, he starts the temple on his own initiative.

In both cases, God makes a conditional promise to dwell among the Israelites. In the Torah portion, God will stay with them if they make a place for God:

And they shall make for me a holy place, and I will dwell in their midst. (Exodus 25:8)

But in the haftarah, God will stay with the Israelites if King Solomon follows the rules:

And the word of God came to Solomon, saying: This house that you are building—if you follow my decrees and you do my laws and you observe all my commandments, to go by them, then I will establish my word with you that I spoke to David, your father: then I will dwell in the midst of the children of Israel, and I will not desert my people Israel. (1 Kings 6:12-13)

The differences between the mishkan and the temple imply two different approaches to religion. The sanctuary God describes to Moses belongs to the people; they make it voluntarily, they move it with them wherever they go, and God dwells among them because they make a holy place for God.

The temple of Solomon belongs to the king; he oppresses his own people in order to procure the materials and labor, he fixes it permanently in Jerusalem, and God dwells among his people because King Solomon obeys God’s rules.

I believe the tent-sanctuary described in the Torah portion represents the ideal approach to communal religion, in which everyone in the community contributes enthusiasm, support, or creativity; in which textual interpretations and rituals are flexible enough to move and change along with the people; and in which everyone makes a holy place for God.

Yet this ideal cannot always be realized. There are times everyone, including me, is too exhausted or too stuck to manage creative communal worship. Sometimes we just need a place to go where the rituals will be fixed and familiar, and where a trusted authority figure is taking care of everything and telling us what to do.

We need both tents and temples.