And God spoke to Moses, saying: “Speak to the Israelites, and they will take voluntary contributions for me. From everyone whose heart makes him willing, you may take my voluntary contributions.” (Exodus 25:1-2)

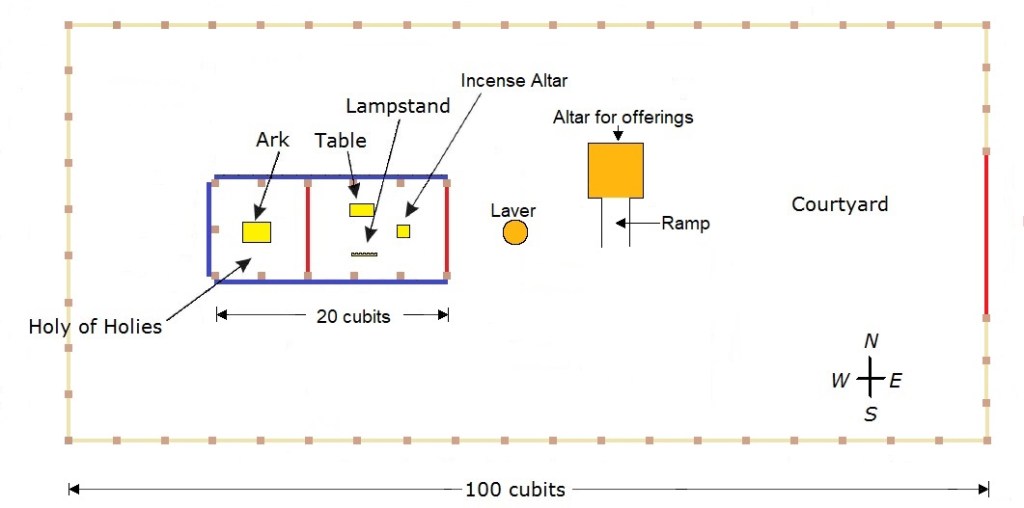

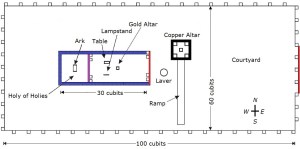

After that opening, this week’s Torah portion, Terumah (Exodus 25:1-27:19), lists the contributions that people can give: gold, silver, and bronze; blue, purple, and scarlet thread made of wool, linen, and goat’s hair; two kinds of tanned leather; acacia wood; olive oil; incense spices; and precious stones.

Then the text says what the materials are for:

“Let them make a holy place for me, and I will dwell among them.” (Exodus 25:8)

Later in Exodus, Moses invites anyone whose heart is moved to bring materials and donate labor to build a portable tent sanctuary for God.

And everyone whose mind was uplifted and everyone whose spirit made him willing brought voluntary gifts for God, for the work of the Tent of Meeting … (Exodus 35:21)

Then all the skilled artisans in the community volunteer to weave and embroider cloth, tan leather, shape wood, forge tools, and assist the master craftsmen Betzaleil and Oholiav in making the holiest objects. When the sanctuary is complete, God moves in.1

The haftarah (accompanying reading from the Prophets) for this week’s Torah portion is 1 Kings 5:26-6:13, which tells how King Solomon acquires wood and stone to build the first permanent temple for God in Jerusalem. This time the labor is done by conscripts instead of volunteers, but God promises to move in anyway.

The king imposes compulsory labor

And God had given Solomon chokhmah, as [God] had spoken. And there was peace between Chiram and Solomon, and the two of them cut a covenant. (1 Kings 5:26)

chokhmah (חָכְמָה) = technical skill; good sense; wisdom from accumulated knowledge.

The best translation of chokhmah here is probably “good sense”. Solomon exhibits good sense when he maintains the alliance of his father, King David, with one of his richest neighbors, King Chiram. Chiram was a 10th-century ruler of the city-state of Tyre, on the coast of a forested region called Lebanon (now a nation by the same name). During his long reign, Chiram turned Tyre into the premier Phoenician city by building a vast trade network.

The first trade agreement between Chiram and Solomon calls for Chiram to provide Solomon with all the cedar and cypress logs he can use, and Solomon to provide Chiram with annual shipments of wheat and olive oil. An exchange of labor is also involved.

And King Solomon raised a mas from all Israel. And the mas was 30,000 men. And he sent them to Lebanon, 10,000 per month; by turns [each man was] a month in Lebanon and two months at his own house. (1 Kings 5:27-28)

mas (מַס) = compulsory labor, forced labor.

Kings in the Ancient Near East often conscripted their citizens to serve in the military, like governments today. But it was also common for kings to conscript people for mas, a less prestigious form of service.

Solomon exhibits chokhmah,good sense, again in this haftarah by limiting his mas of Israelite laborers in Lebanon to every third month. This arrangement leaves the men free to return home and work on their own families’ farms and businesses the other two months, making the mas a tolerable burden.

The Israelite conscripts working in Lebanon every third month are felling cedar and cypress trees and hauling the trunks to the coastline under the supervision of King Chiram’s men. The men of Tyre then lash the logs into rafts and sail them to a place where King Solomon’s men will pick them up and transport them to Jerusalem.2 In Jerusalem, the wood is used in the construction of God’s temple, and later in King Solomon’s palace and associated buildings.

Solomon’s building projects also require a lot of stone, but he can get good stone from the hills of Israel.

Solomon also had 70,000 porters and 80,000 quarriers in the hills … And the king gave the order, and they moved great stones, expensive stones, for the foundation of [God’s] house: hewn stones. (1 Kings 5:29)

The haftarah does not say whether the quarriers and porters working in the hills are paid employees, or conscripted for mas. A king in that civilization was more likely to use conscripts, who would be fed, but would not be free to quit their mas until their terms of service were completed.

After the basic structure of the temple has been erected, but before there are any interior walls or furnishings, God speaks to King Solomon.

Then the word of God happened to Solomon, saying: “This house that you are building—if you follow my decrees and you act [according to] my laws, and you guard all my commands, following them—then I will fulfill with you my word that I spoke to David, your father. And I will dwell among the Israelites, and I will never forsake my people Israel.” (1 Kings 6:11-13)

Israelites as volunteers versus subjects

In this week’s portion from Exodus, God tells Moses: “Let them make a holy place for me, and I will dwell among them.” The people deserve God’s protective presence because they willingly donate their time, skills, and valuables to make a place for God. The relationship is between God and all the Israelites. But in this week’s haftarah from 1 Kings, God tells Solomon: “If you follow my decrees and you act [according to] my laws, and you guard all my commands …” God uses the singular form of “you” throughout the clause beginning with “if”; the contractual relationship is between God and the king. In return, God promises to support Solomon as king, and also to “dwell among the Israelites”. In other words, God promises to be present among the Israelites for the sake of their king’s obedience to God. Perhaps the assumption is that if the king of Israel obeys God’s rules, he will also enforce them among his people.

Who is conscripted?

Later during King Solomon’s reign, well after this week’s haftarah, he adopts the more traditional policy of favoring his own ethnic group over the people the Israelites conquered:

All the people who were not from the Israelites—those who were left from the Amorites, the Hittites, the Perizites, and Chivites, and the Jebusites, their children … whom the Israelites were not able to dedicate to destruction, Solomon laid on them a mas of slavery until this day. But Solomon made no Israelite a slave. Instead they became men of war, and his servants, and his commanders, and his captains, and the officers of his chariots and his horsemen. (1 Kings 9:20-22)

According to earlier books in the bible, the Canaanite peoples that were not wiped out were subject to a permanent mas starting with the conquest of Joshua.3 Kings in the Ancient Near East normally imposed mas on defeated enemies, relocating them to wherever brute labor was needed; for example, the Neo-Assyrian King Sennerachib did this when he conquered the northern kingdom of Israel.4

The policy of giving conquered enemies either mas or death is laid out in the book of Deuteronomy:

And if [the town] answers you with peace and opens to you, then all the people you find in it will be yours for a mas, and to serve you. (Deuteronomy 20:11)

Ironically, in the book of Exodus God helps the Israelites to escape from Egypt and conquer Canaan because they are suffering so much from the mas two pharaohs in a row imposed on them.5

When mas is too much

During the first twenty years of his reign, Solomon completes the temple for God, and God fills it with a cloud of glory to prove that God is in residence.6 But during the second half of his forty-year reign, Solomon exhibits less chokhmah. He takes 700 foreign wives, far more than needed to be strategically connected by marriage with every kingdom in the Ancient Near East, and builds shrines to some of his wives’ gods.7

Apparently he also institutes harsher mas on the ethnic Israelites—at least on the ten tribes that live more than a day’s journey north of Jerusalem.

Late in his reign, King Solomon appoints a capable man named Yeravam (Jereboam in English) to be in charge of the conscripts for mas from the tribes of Efrayim and Menashe in the north. Then a prophet predicts that someday Yerevam will be the king of the ten northern tribes.8 Shortly after that Yeravam flees to Egypt, apparently because King Solomon finds out and orders his execution.9

After Solomon dies, his son Rechavam (Rehoboam in English) goes to Shekhem, a city north of Jerusalem, to be anointed king. Yerevam returns from Egypt in time for the ceremony. He and his Israelite supporters tell Solomon’s son:

“Your father made our yoke hard. And you, now, lighten the hard labor of your father and the heavy yoke he put on us, and we will serve you.” (1 Kings 12:3-4)

Rechavam tells them to come back in three days for his answer. When they do, he says:

“My father made your yoke heavy, and I will add to your yoke! My father flogged you with whips, and I will flog you will scorpions!” (1 Kings 12:14)

The northern Israelites then renounce any fealty to Solomon’s son.

And King Rechavam sent Adoram, who was over the mas. But all the Israelites pelted him with stones and he died. (1 Kings 12:18)

Rechavam flees back to Jerusalem, where he rules only the southern Kingdom of Judah: the arid territory belonging to the tribes of Judah and Benjamin. But Yeravam becomes the first king of the northern Kingdom of Israel, reigning over the more fertile land belonging to the other ten tribes of Israelites—just as God’s prophet had predicted.

When I was a teenager, most of the boys in my high school lived in the shadow of the valley of death. Though they did not admit it to girls, they were afraid of being drafted and sent to Vietnam to die.

Many of their fathers were veterans of World War II, and considered military service something to be proud of—at least during the early part of the roughly ten years when the United States was fighting on the side of South Vietnam. But a large number of younger Americans were morally opposed to sending Americans to kill people in Vietnam.

In the culture of the Hebrew Bible, and in many other times and places, being in the military was an honorable condition. Men returning from war were treated as heroes because they had risked their lives for their cause or their country—whether they were volunteers or conscripts.

But the teenage boys I knew in Massachusetts saw conscription for the war as an ignoble mas, forced labor in the jungle leading to death for no good reason. They would have preferred carrying heavy stones and logs to a construction site for a temple or palace.

The more body bags Americans saw on television, the less popular the war became.

When the pharaoh subjected Israelite men to mas for too many years in the book of Exodus, they cried out to God and God rescued them. When King Rechavam threatened the northern Israelites with a more severe mas in the first book of Kings, they renounced their allegiance and chose a king of them own. When a burden is too severe, it cannot be imposed forever.

- Exodus 40:33-38.

- 1 Kings 5:22.

- Joshua 16:10, 17:13; Judges 1:28-1:35.

- 2 Kings 17:6, 17:23-24, and 18:11 report Neo-Assyrian King Sargon II capturing the capital of the Kingdom of Israel and relocating tens of thousands of Israelites in the eastern part of its empire. Foreigners are depicted doing heavy labor for Neo-Assyrian kings on relief sculptures.

- Exodus 1:11-14, 3:7-10.

- 1 Kings 8:10-11.

- 1 Kings 11:1-10.

- 1 Kings 11:26-39.

- 1 Kings 11:40.