(This is my sixth post in a series about the interactions between Moses and God on Mount Sinai, and how their relationship evolves. If you would like to read one of my posts about this week’s Torah portion, Terumah, you might try: Terumah: Insecurity.)

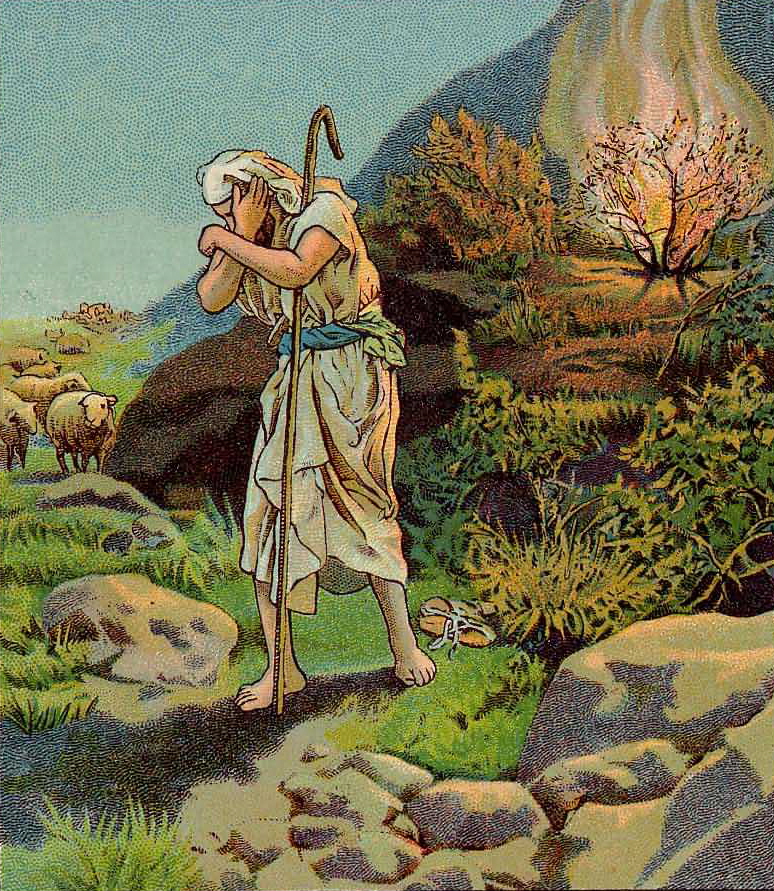

Moses hears God speak to him for the first time out of the fire in the thornbush on Mount Sinai. (See my post: Shemot: A Close Look at the Burning Bush.) God has already decided to use devastating miracles to liberate the Israelites in Egypt, but needs a human agent to persuade the Israelites to leave for Canaan and the pharaoh to let the Israelites go.

For this job, God picks an Israelite by birth who was raised by Egyptian royalty, and is now herding sheep in Midian. Moses’ assets are that he is curious and open to new ideas, he empathizes with the underdog, he is humble, and he is sufficiently awed to hide his face when he hears a divine voice speaking out of the fire. (See my post: Shemot: Empathy, Fear, and Humility.)

But he does not want to go. He knows he is not an adept speaker. (See my post: Shemot: Not a Man of Words.) And he longs to continue his safe and peaceful life in Midian. So he tries five times to excuse himself from the mission. (See my post: Shemot: Names and Miracles.)

In this first conversation on Mount Sinai, Moses sounds like an anxious child, and God sounds like a patient parent. It takes God a long time to reassure Moses enough so he will cooperate with God’s plan. Finally God promises that Moses’ brother Aaron will be his spokesman in Egypt, and Moses stops trying to get out of the job. (See my post: Shemot: Moses Gives Up.) After a brief stop at his father-in-law’s camp, he heads back to Egypt.

A year or two passes before Moses meets God on Mount Sinai again. During that time, God continues to give Moses instructions, and occasionally Moses asks God a question. These conversations are silent, inside Moses’ mind.

Does Moses change during this period in Egypt? Does his relationship with God change?

Shemot: Moses wins and loses the people’s trust

Aaron meets Moses on the road as he heads across the Sinai Peninsula toward Egypt.

And Moses told Aaron all the words with which [God] had sent him, and all the signs [God] had instructed him in. Then Moses and Aaron went, and they gathered all the elders of the Israelites. And Aaron spoke all the words that God had spoken to Moses, and he did the signs before the eyes of the people. And the people trusted … (Exodus 4:28-31)

The text does not say whether the Israelites trust Moses, whom they do not know, or only Aaron, one of their own elders. Either way, they believe they are hearing the words of their own god.

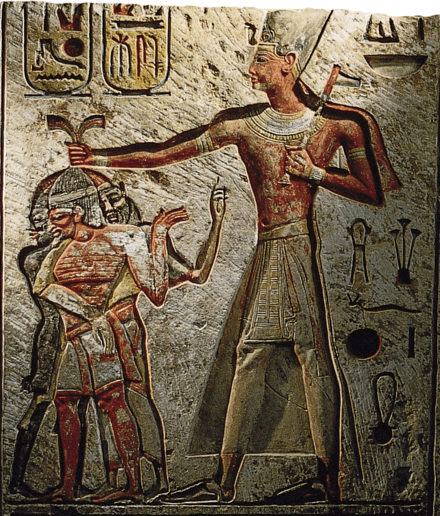

And afterward Moses and Aaron came and said to Pharaoh: “Thus says Y-H-V-H, the god of Israel: ‘Let my people go, and they will observe a festival for me in the wilderness!’” (Exodus 5:1)

The text does not say which brother is doing the actual speaking. The pharaoh says no, and Moses and Aaron clarify their request:

“Please let us go a distance of three days into the wilderness, and we will make slaughter-offerings to Y-H-V-H, our God …” (Exodus 5:3)

Instead, the pharaoh increases the workload of the Israelites, and they turn against Moses and Aaron.1

Then Moses returned to Y-H-V-H and said: “My lord, why have you done harm to this people? Why did you send me? Since I came to Pharaoh to speak in your name, he has done harm to this people. And you certainly have not rescued your people!” (Exodus 5:22-23)

Until now, Moses has only responded after God spoke to him. This is the first time Moses initiates a conversation with God.2

On Mount Sinai, God warned Moses that the pharaoh would not let the Israelites go until after God had inflicted some devastating miracles on Egypt.3 Has Moses forgotten? Or is he making a different point with his questions?

Eleventh-century rabbi Chananel viewed Moses’ question “Why have you done harm to this people?” as an enquiry about the problem of evil. “This is not to be understood as a complaint or insolence, but simply as a question. Moses wanted to know the use of the [divine] attribute which decrees sometimes afflictions on the just, and all kinds of advantages for the wicked …”4

In the 14th century Rabbeinu Bachya saw Moses’ first question as an acknowledgement that God does do harm to people God favors. “The Torah wanted to inform us that improvements or deteriorations in the fate of the Jewish nation are the result of God’s doing, not of someone else’s doing. By his very question, Moses wanted to make it clear that he understood this. After all, evil does originate with God, though in a more indirect manner than good.”5

Their explanations are theologically interesting, but Moses has not engaged in such abstract thinking yet in the storyline of Exodus, and his second question, “Why did you send me?”, shows he is taking the situation personally. Other commentators have offered a more likely explanation: that Moses thought God would move quickly once he has spoken to the pharaoh, and life would improve for the Israelites until the final miracle freed them altogether. Therefore he asks why God sent him before the divine deliverance was at hand.6

According to 16th-century rabbi Ovadiah Sforno, Moses’ second question means: “Why did You make me the one to be the immediate cause of [their suffering]?”7

Moses’ questions to God remind me of a child complaining, “It’s not fair!” To his credit, Moses points out that the unfairness to the Israelites (why have you done bad to this people?), as well as unfairness to himself (why did you send me?).

According 19th-century rabbi S.R. Hirsch, Moses is telling God: “You caused this new calamity. You did not just remain aloof when it happened; rather, You provoked it through my mission.” Then Hirsch explains: “His mission has been a complete failure. … Moshe, too, is doubting himself; indeed, who, if not Moshe, would now not have heightened misgivings about his own capability, would now not ask himself whether he had mishandled his mission?”8

He also goes so far as to accuse God by saying: “and you certainly have not rescued your people!”. It is human nature to assign the blame to someone else when you suspect you are partly responsible for a disaster.

Moses may feel as insecure as ever about speaking to other human beings, but he is much bolder now when he speaks to God. He treats God the way an adolescent might treat a reliable parent at a moment of crisis.

And God’s response is mild enough:

“Now you will see what I will do to Pharaoh.” (Exodus 6:1)

Va-eira: Moses trusts God—and himself

When God tells Moses to go speak to the pharaoh again, Moses replies:

“Here, the Israelites don’t listen to me. How will Pharaoh listen to me? And I have foreskin-covered lips!” Then God spoke Moses and to Aaron, and commanded them … (Exodus 6:12-13)

Moses may trust God to listen to him patiently, but he still does not trust himself to be a convincing speaker. He uses the biblical metaphor of the foreskin to indicate that his power to speak well is blocked.9

Perhaps God thinks that Moses’ ears are also foreskin-covered, since God switches back to addressing Moses and Aaron at the same time.

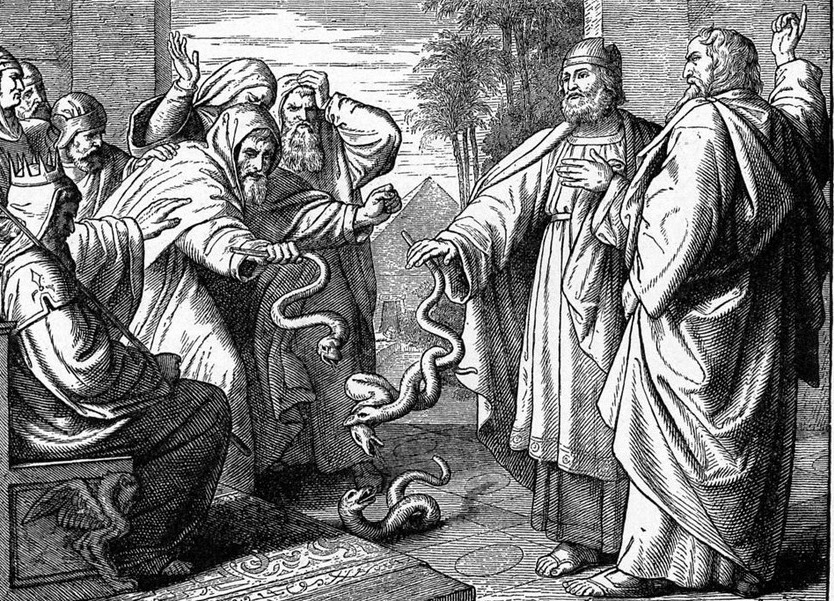

They obey God and return to the pharaoh to demonstrate the miraculous sign God gave Moses on Mount Sinai, in which his staff turned into a snake. This time Aaron is holding the staff.10

Then God dictates what Moses must say to the pharaoh the next morning at the Nile, and assigns Aaron to wield the staff to initiate the miracle of the water turning to blood.11 The miracles continue, with Moses repeating God’s words to the pharaoh, and Aaron making the gestures. Clearly Moses can speak upper-class Egyptian correctly. But if he is an insecure introvert, as I proposed in my post Shemot: Not a Man of Words, he needs to know ahead of time what to say, and God tells him.

Then Moses begins adding a few words of his own. After the miracle (or plague) of frogs, the pharaoh tells Moses and Aaron that if they beg God to remove the frogs, he will let the Israelites go make their offerings to God. Moses asks the pharaoh to choose the time for the divine frog extermination, “so that you will know there is none like Y-H-V-H, our God.” (Exodus 8:5-6)

He trusts God to back him up by killing the frogs on the day the pharaoh designates—and God does.

After the fourth plague (arov (עָרֺב) = swarms, mixtures of insects), the pharaoh tells Moses and Aaron that he will let the people make their offerings to God as long as they stay inside Egypt. Apparently on his own initiative, Moses replies:

“It would not be right to do thus, since we will slaughter for Y-H-V-H, our God, what is taboo for Egyptians. If we slaughtered what is taboo for Egyptians in front of their eyes, then wouldn’t they stone us? Let us go on a journey of three days into the wilderness …” (Exodus 8:22-23)

The pharaoh agrees this time, and Moses agrees to ask God to remove the swarms. But he adds:

“Only let Pharaoh not trifle with us again, by not letting the people go to make slaughter-offerings to Y-H-V-H!” (Exodus 8:25)

If Moses is an introvert, then he has probably spent days mulling over what he might say to the pharaoh in various situations. When one of those situations arises, he does not need to wait for either God or Aaron; he can simply deliver one of the replies he practiced. (This is how I have managed to speak up in difficult social situations despite my introversion.)

Moses is also getting used to being listened to. His trust in himself, as well as in God, is increasing.

Bo: Moses transcends himself

After the penultimate plague, three days of utter darkness for all the Egyptians, the pharaoh tells Moses that all the Israelites may go into the wilderness, even the women and children, as long as their livestock stays behind. Moses is now accustomed to the pharaoh bargaining in bad faith, and he has his answer ready.

And Moses said: “You, too, must give into our hand slaughter-offerings and burnt offerings, and we will make them for Y-H-V-H, our God. And also our own livestock will go with us; not a hoof will remain behind. Because we will take from them to serve Y-H-V-H, our God, and we ourselves will not know what we will serve God [with] until we arrive there.” (Exodus 10:25-26)

The 18th-century commentary Or Hachayim noted: “At any rate, this answer of Moses to Pharaoh was obviously one that Moses invented and is not to be regarded as an instruction given to him by God.”10

The pharaoh loses his temper, possibly because Moses’ answer is obviously an excuse.

Then Pharaoh said to him: “Go away from me! Watch out against seeing my face again, because the moment you see my face you will die!” And Moses said: “You spoke the truth! I will not see your face again!” (Exodus 10:28-29)

Perhaps Moses forgets that God has saved one final plague to inflict upon Egypt. According to many commentators, God hurries to instruct Moses about it before he stalks out of the pharaoh’s audience chamber.11

Moses then follows God’s new instructions by announcing that at midnight every Egyptian firstborn male, from the pharaoh’s oldest son to the firstborn of cattle, will die. Then he adds something God did not tell him to say.

“And then all these courtiers of yours will come down to me and prostrate themselves to me, saying: ‘Go! You and all the people who follow you!’ And after that I will go.” And he walked away from Pharaoh bahari af. (Exodus 11:8)

bahari af (בָּחֳרִי־אָף) = with the hot nose (an idiom for “in anger”).

Moses’ final words to the pharaoh do not sound like something an introvert rehearsed ahead of time. Carried away by his anger in the moment, Moses says the first thing that comes into his head.

It was standard procedure to prostrate oneself before a king in order to receive permission to speak; Moses and Aaron would have done it at every audience with the pharaoh. Now Moses says that the pharaoh’s courtiers will come to him and prostrate themselves, as if he were a king.12

It does not happen exactly the way Moses’ inflamed imagination pictures it. At midnight, when the firstborn Egyptians are dying and people are wailing in every Egyptian house, the pharaoh himself summons Moses and Aaron and commands the Israelites to leave Egypt and take their flocks and herds with them.

They march out of Egypt with everything they own, as well as some gold, silver, and clothing “borrowed” from Egyptians. They leave behind a country devastated by God’s ten miraculous plagues, a country in which everyone from pharaoh to commoner acknowledges that the God of Israel is the most powerful god.

The first stage of Moses’ mission, and God’s, has succeeded.

To be continued …

- Exodus 5:21.

- Rabbi Adin Even-Israel Steinsaltz, The Steinsaltz Tanakh, Koren Publishers, Jerusalem, 2019, quoted in www.sefaria.org.

- Exodus 3:19-20.

- Rabbeinu Chananel (Rabbi Chananel ben Chushiel), as quoted in other commentaries, translation in www.sefaria.org.

- Rabbeinu Bachya (Rabbi Bachya ben Asher, 1255–1340), translation in www.sefaria.org

- E.g. Rabbi Abraham ibn Ezra (12th century), Ramban (13th-century rabbi Moses ben Nachman), Chizkuni (a 13th-century compilation), Or Hachayim (by 18th-century Rabbi Chayim ben Moshe ibn Attar).

- Rabbi Ovadiah Sforno, translation in www.sefaria.org.

- Exodus 7:9-10.

- Leviticus 26:41 says that God will welcome the Israelites back “if their foreskin-covered heart humbles itself”. Jeremiah 6:10 says that the ears of the Judahites are “foreskin-covered, and they cannot listen”.

- Exodus 7:14-20.

- Or HaChayim, by Rabbi Chayim ben Moshe ibn Attar, translation in www.sefaria.org.

- E.g. Or HaChayim, ibid.

- Or HaChayim, ibid.