The same word, avodah, means both “service” and “slavery” in Biblical Hebrew. Just as today we consider it virtuous to serve a good cause, the ancient Israelites considered it virtuous to serve God. But is it ever virtuous to serve a human master? Or to be one?

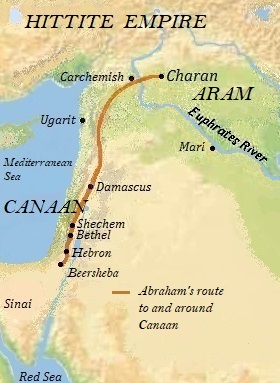

The word avodah first appears in the book of Genesis/Bereishit, after Jacob works for his uncle Lavan for seven years as his bride-price for Rachel. When Lavan gives him Rachel’s sister Leah as a bride instead, Jacob complains. Lavan replies that Jacob can marry Rachel in only one week, but then he owes Lavan another seven years of “avodah that ta-avod with me”. (Genesis/Bereishit 29:7)

avodah (עֲבֺדָה) = service, slavery, labor. (From the root verb avad, עָבַד = serve, be a slave, perform rites for a god, work.)

ta-avod (תַּעֲבֺד) = you shall serve, you shall be a slave. (A form of the verb avad.)

When Jacob agrees, he is voluntarily selling himself as a temporary slave, i.e. an indentured servant who has no rights during his term of indenture, but is free once it ends.

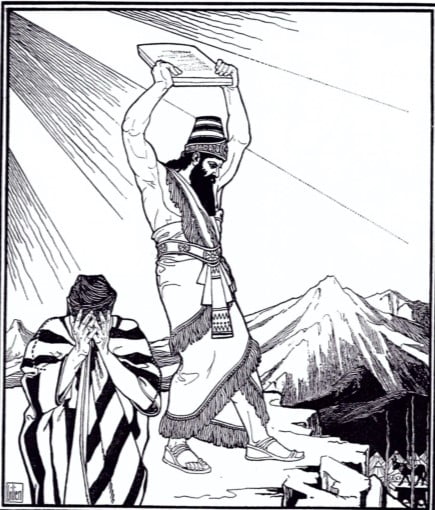

Another type of involuntary labor is corvée labor, when a ruler or feudal lord imposes unpaid labor on people for certain periods of time. In Exodus/Shemot, the Pharaoh decides to impose corvée labor on the resident Israelites.

The Egyptians, vaya-avidu the Israelites with crushing torment, and made their lives bitter with hard avodah with mortar and bricks, and with every avodah in the field, all of their crushing avodah that avdu. (Exodus/Shemot 1:13-14)

vaya-avidu (וַיַּעֲבִדוּ) = they enslaved, they forced to work. (Another form of the verb avad.)

avdu (עָבְדוּ) = they labored at, they slaved away at.

Yet the Torah accepts that the Israelites themselves own slaves, and it provides laws granting slaves limited rights. These rights are more limited for foreign slaves (Canaanites as well as people whom Israelites defeat in battle and bring home as booty) than for slaves who are fellow Israelites. Out of the first eleven laws in this week’s Torah portion, Mishpatim (“Laws”), five concern the treatment of slaves. The first two laws set terms for Israelite slaves:

If you acquire a Hebrew eved, six years ya-avod … (Exodus 21:2)

And if a man sells his daughter as an amah … (Exodus 21:7)

eved (עֶבֶד), plural avadim (עֲבָדִים) = (male) slave; dependent subordinate (such as an advisor or administrator) to a ruler. (From the root verb avad.)

ya-avod (יַעֲבֺד) = he will work for a master, be a slave, serve. (A form of the verb avad.)

amah (אָמָה) = foreign or Israelite slave-girl; foreign slave-woman.

Three more laws in Mishpatim address the most egregious abuses of foreign slaves:

And if a man strikes his eved or his amah with a stick and he dies … (Exodus 21:20)

And if a man strikes the eye of his eved or his amah and destroys it … (Exodus 21:26)

If the ox gores an eved or an amah … (Exodus 21:32)

Although the books of Leviticus and Deuteronomy upgrade the laws in this week’s Torah portion and grant both foreign and Israelite slaves additional rights,1 the institution of slavery is never outlawed in the Hebrew Bible.2

Temporary slaves

There is no requirement that foreign slaves must be freed. Unless an owner decides to release a slave in exchange for payment, the condition of slavery is permanent, and the slave is inherited by the owner’s heirs.3

But an Israelite slave is always temporary, unless he himself chooses to make his condition permanent.4

A free Israelite man who is impoverished or indebted, and has sold everything else he owns, may sell himself. That way he and his family will have food, clothing, and shelter while he works for his master. In addition, a court can sell a convicted thief if he does not have the means to repay the person he stole from.5

A free Israelite man who is impoverished or indebted, and has sold everything else he owns, may sell himself. That way he and his family will have food, clothing, and shelter while he works for his master. In addition, a court can sell a convicted thief if he does not have the means to repay the person he stole from.5

An Israelite girl becomes a slave if her father sells her while she is still a minor. That way her father receives a payment at once in lieu of the bride-price he would normally receive when she reaches puberty and marries.

Unlike a foreign slaves, Israelite slaves must be given the option of freedom after six years, in the Jubilee year, or when their kinsmen redeem them, whichever comes first.6 Meanwhile, temporary slavery is acceptable as long as the master follows the laws, starting with the laws laid out in this week’s Torah portion.

*

If you acquire a Hebrew eved, six years ya-avod, and in the seventh he shall leave free, without charge. If he comes alone, he leaves alone. If he is the husband of a woman, then she leaves with him. (Exodus 21:2-3)

The slave does not have to repay his master for any expenses incurred during the period of his servitude. And if he was married when he was sold, his master must also take in his wife and children, so they will not go homeless.7

If his master gives him a woman and she bears him sons or daughters, the woman and her children will belong to her master, and he [the Israelite slave] will leave alone. (Exodus 21:4)

The Israelite slave’s master can, however, use him for stud service, to breed children with a non-Israelite female slave. These children will be permanent slaves, like their mother.8

*

The Torah portion Mishpatim also lays out the terms of service for a female Israelite slave. Even free women in ancient Israel were considered the property of their fathers, husbands, or nearest male kin, but the only Israelite female called a slave (amah) was a girl sold by her father.

And if a man sells his daughter as an amah, she shall not leave like the avadim. If she is undesirable in the eyes of her master who had designated her for himself, he shall turn her over [arrange to have her redeemed]. He shall not exercise dominion over her to sell her to strange people, since he has broken faith with her. (Exodus 21:7-8)

In the Torah a man can buy a future wife or concubine, for himself or for his son, when she is still underage. Her purchase price is then considered an advance payment of the bride-price that a groom pays before he marries. By this means impoverished fathers could sell their daughters for cash without waiting for them to come of age.

If the girl reaches puberty and her owner decides not to marry her after all, he must arrange for her family to redeem her by repaying him; he cannot sell her to anyone else. If her owner bought her as a future wife for his son, the marriage must take place.

And if he designated her for his son, he shall treat her as is the law of daughters: if he marries another, he shall not diminish her [the former amah’s] meals, covering [clothing or honor], or right to marital intercourse. (Exodus 21:9-10)

Once the girl marries her owner or her owner’s son, she must be treated like any wife and given food, clothing, honor, and sex, regardless of whether her husband likes another of his wives better.

In other words, the amah’s owner is obligated to make an acceptable provision for her when she comes of age. The three things the Torah considers most acceptable are marriage to the owner, marriage to the owner’s son, or a return to her original family.

And if he [the owner] does not do [any of] these three things, she shall leave without charge, without any silver. (Exodus 21:11)

If her owner does not provide for her in any of the three preferred ways, then he must set her free like a male Israelite slave who has completed his period of service, without charging her anything. (Non-Israelite slaves would have to pay their owners to be set free.) Freedom was an inferior option for a young woman in ancient Israelite society, since it was hard for a single woman to make a living, but at least it was better than being sold to an outsider.

*

The Torah’s laws about slavery, in this week’s Torah portion and elsewhere, provide some rights for slaves in a society where slavery is normal. Does that mean these laws have only historical interest to us today?

Alas, no. In the United States, for example, the conquering Europeans treated the indigenous peoples the way the conquering Israelites treated the Canaanites, refusing to grant them the same legal rights to life and liberty. The Americans in power also enslaved people who were kidnapped from their homes in Africa, just like the Israelites enslaved foreigners captured in battle. Although Native and African Americans now have legal equity, they remain at a disadvantage due to earlier injustice and continuing prejudice.

Furthermore, throughout the United States there are still many people who are so impoverished, in terms of finances and/or knowledge, that they “sell” themselves by doing degrading, dangerous, or illegal work in order to feed themselves and their families. Our “social safety net” limits the level of impoverishment in some circumstances, but it is currently being reduced rather than expanded.

Those who struggle under a disadvantage should not be left alone to starve. The Torah’s solution, temporary slavery, is essentially adoption by a wealthier family that can support the impoverished in exchange for their labor. But with all our resources in the United States, we can do better. Collectively, through taxes, we can and should rescue the destitute with solutions that give them basic living expenses, health care, and education. Other rich countries today are farther along this path; it is time for Americans to catch up and stop treating disadvantaged people like slaves.

—

- E.g. Deuteronomy 15:12-14 on Israelite slaves, Deuteronomy 21:10-11 on foreign female slaves (see my post Ki Teitzei: Captive Soul).

- The Talmud, Gittin 65a, claims that slavery was abolished when the first temple fell and there were no more Jubilee years when all Israelite slaves were freed and their family lands returned to them. But the books of Ezra and Nehemiah count 7,337 male and female slaves among the households that returned from Babylonia to Jerusalem to build the second temple (Ezra 2:65, Nehemiah 7:67).

- Leviticus 25:44-46.

- Exodus 21:5-6 in this week’s Torah portion.

- Exodus 22:2 in this week’s Torah portion.

- Male Israelite slaves are freed in the seventh year in Exodus 21:2-3; female Israelite slaves have the same right by the time of Deuteronomy 15:17. Every fiftieth year all Israelite slaves are freed and their ancestral lands are returned to them (Leviticus 25:10-28, 25:39-43). A male slave’s kinsmen can redeem him before his term is up by paying for his remaining years (Leviticus 25:50-52), and a female slave’s kinsmen can redeem her when she reaches puberty, providing that her master or his son no longer want to marry her (Exodus 21:7-8).

- Rashi (11th-century rabbi Shlomoh Yitzchaki), Rambam (12th-centery rabbi Moses ben Maimon), Ramban (13th-century rabbi Moses ben Nachman), and subsequent tradition.

- Rashi and Ramban on Exodus 21:4.