The first time God changed Moses’ staff into a snake was on Mount Sinai, when God was giving him the signs he would use to convince the Israelites in Egypt that he was a genuine prophet. (See last week’s post, Shemot: Snake Staff, Part 1.)

The second time God transformed the staff was at the meeting Aaron set up between his brother Moses and elders of the Israelites in Egypt.

And Aaron spoke all the words that God had spoken to Moses, and he performed the signs in the sight of the people. And the people trusted him, and they heard that God had taken up the cause of the Israelites and had seen their misery and noticed them. And they bowed to the ground. (Exodus 4:30-31)

So far, so good. The next step was to persuade Pharaoh that God had sent them.

And afterward Moses and Aaron came and said to Pharaoh: “Thus says Y-H-V-H, the God of Israel: Let my people go so they will celebrate a festival for me in the wilderness.” But Pharaoh said: “Who is Y-H-V-H, that I should listen to his voice and let the Israelites go? I do not know Y-H-V-H, and furthermore, I will not let the Israelites go.” (Exodus 5:1-2)

This might have been a good time for the brothers to use the magic staff to demonstrate that they are real emissaries of a real god. But God had not ordered it. Moses and Aaron merely talked a little longer, and then Pharoah decided to increase the workload of the Israelites instead.

The Israelites lost faith in Moses and in the promised rescue from Egypt. The Torah portion Shemot ends shortly after the Israelite foremen complain to Moses and Aaron:

“May God examine you and judge, since you made us smell loathsome in the eyes of Pharaoh and in the eyes of his courtiers, putting a sword in their hand to kill us!” (Exodus 5:21)

Marvel in the palace

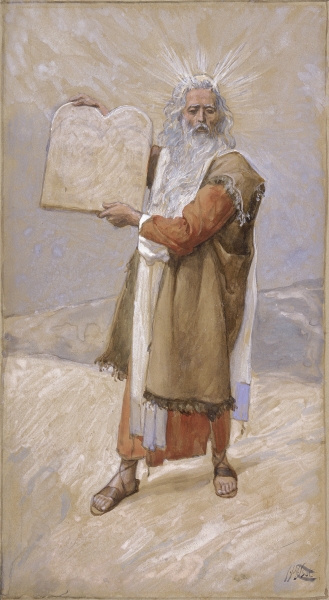

This week’s Torah portion, Va-eria (Exodus 6:2-9:35), opens with some repetitions of the story line and a genealogy.1 Then God finally tells Moses and Aaron to demonstrate the transformation of the staff to Pharaoh.

And God said to Moses and to Aaron: “When Pharaoh speaks to you, saying: ‘Give me your marvel!’ then you will say to Aaron: ‘Take your staff and cast it down in front of Pharaoh!’ It will become a tanin.” Then Moses and Aaron came to Pharaoh, and they did just as God had commanded; Aaron cast down his staff in front of Pharaoh and his courtiers, and it became a tanin. (Exodus 7:8-10)

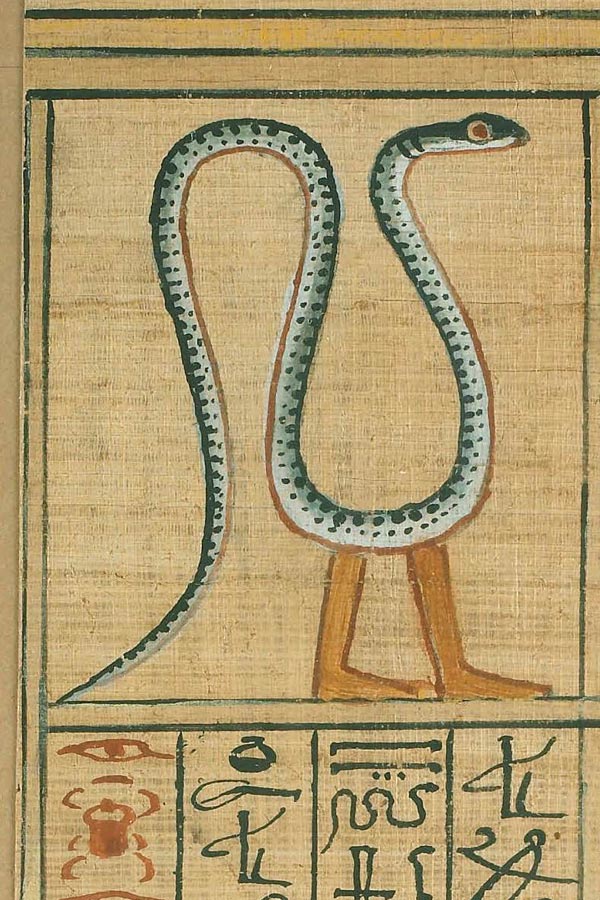

tanin (תַנִּין) = sea monster, crocodile, snake.2

When God transformed Moses’ staff on Mount Sinai (in a tale some scholars attribute to an E source), it became a nachash (נָחָשׁ) = snake, serpent. Now (in the tale from a P source) it becomes a tanin. Different source stories used somewhat different terminology.

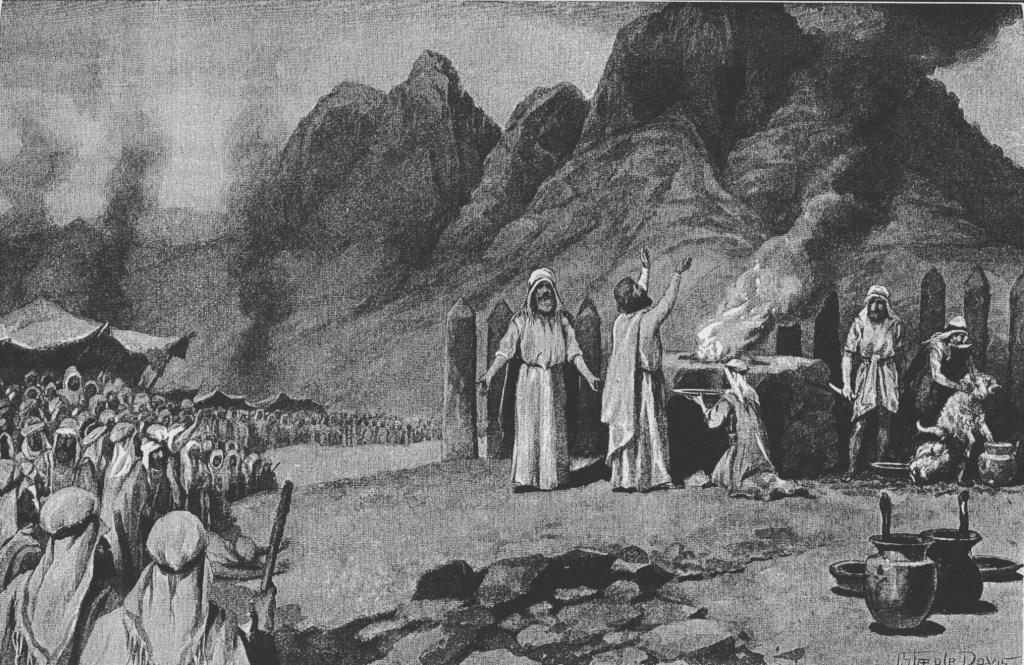

And Pharaoh also summoned his wise men and his sorcerers, and they, also they, the chartumim of Egypt, did this with their spells. (Exodus 7:11)

chartumim (חַרְטֻמִּים) = literate Egyptian priests with occult knowledge.

The word chartumim is often translated as “magicians”, but these Egyptian dignitaries were not magicians in the modern sense: people who create illusions and trick their audiences. The ancient Egyptians believed that the gods created and maintained the universe with “heka”, a cosmic power that priests could also tap into and use to manipulate reality.)

Each one cast down his staff, and it became a tanin. But Aaron’s staff gulped down their staffs. (Exodus 7:12)

The Egyptian priests use “heka” to produce the same marvel that God makes: a staff turning into a tanin. But the magic of the God of Israel proves superior to the magic of the Egyptian priests, since God’s staff swallows their staffs.

This is a significant coup, considering the nature of the crocodile and snake gods in Egyptian theology.

The crocodile in Egyptian theology

The transformation of a staff into a crocodile would remind Egyptians of their crocodile god, Sobek, credited with both creating the Nile and giving strength to the pharaoh. If the God of Israel has power over Sobek, Pharaoh and the whole country are in danger.

The concept of a staff becoming a crocodile would not seem strange to the Egyptians. In an Egyptian tale written as early as 1600 B.C.E., the Egyptian priest Webaoner made a wax crocodile “seven fingers long”, and when his assistant threw it into a lake it became a real crocodile and swallowed up the priest’s enemy. When the king arrived, Webaoner caught the real crocodile, and it shrank and turned back into wax.3

The snake in Egyptian theology

The idea of a staff changing into a snake may have come from Egyptian rituals in which priests carried rods with heads shaped like snakes, as depicted in a 15th-century B.C.E. tomb painting.

The sudden appearance of a snake in Pharaoh’s audience chamber would remind the Egyptians of the snake god Apep. Apep was the god of chaos, evil, and darkness, the enemy of the sun god, Ra. Ra was the god of order and light, and crossed the sky from east to west every day. Every night the sun went down in the west and Ra traveled through the underworld to where the sun was due to rise again in the east. During this nightly underground crossing, Ra fought Apep, who lived in the underworld of the dead. For centuries Egyptian priests helped Ra in the battle by making wax models of Apep and spitting on them, mutilating them, or burning them while reciting spells to kill the evil god.4

Another Egyptian snake god was Nehebu-kau, a variant of Apep who had become a benign underworld god by the 13th century B.C.E., when the Exodus story was set. Nehebu-kau ws one of the 42 gods who judged the souls of the deceased. (Another was the crocodile god Sobek.) When souls of the dead passed the test for good behavior during life, Nehebu-kau gave them the life-force ka so they would have an afterlife. (Apep, on the other hand, was called “Eater of Souls”.)

When Aaron’s snake swallows the Egyptian priests’ snakes, it signals that the whole Egyptian cosmic order is in danger. Can Ra defeat a god even more powerful than Apep? Will there be any afterlife if Nehebu-kau is overthrown?

Pharaoh versus his priests

But Pharaoh’s mind hardened, and he did not listen to them, just as God had spoken. (Exodus 7: 13)

The next step is the first of the miraculous plagues that will destroy Egypt, just what God predicted to Moses in the Torah portion Shemot .

We can assume the Egyptian chartumim in the book of Exodus are shocked and alarmed when Aaron’s snake-staff gulps down all of theirs. It is an obvious omen that the God of Moses and Aaron will triumph over their pharaoh, and over all Egypt. But they do not want to believe this omen, so they return to do more magic for Pharaoh. They gamely use “heka” to reproduce God’s plagues of blood and frogs, at least in miniature.5 But they cannot replicate God’s third plague, lice.6 And at that point they acknowledge that the power behind the plagues is a serious danger to their world.

And the chartumim said to Pharoah: “It is a finger of a god!” But Pharaoh’s mind hardened, and did not listen to them. (Exodus 8:15)

Modern Torah readers are familiar with the idea that God is omnipotent. For us, the magic tricks that God arranges with a shepherd’s staff might seem like a sideshow before the main action of the ten plagues begins.

Yet it is necessary for Moses to prove to both the Israelites and the Egyptians that he really is speaking for a powerful god, and that his God is more powerful than any Egyptian god or Egyptian magic. Otherwise the Israelites will never follow him out of Egypt. And otherwise the pharaoh will attribute the plagues to other deities.

Some people are better than others at noticing signs and drawing long-term conclusions. Moses notices the subtle miracle of the bush that burns without being consumed, and walks right over to find out more.

The chartumim a a bit slower. They do not warn Pharaoh that Egypt is doomed right after the snake-staff demonstration; they are probably hoping to uncover an explanation consistent with their world-view. But when they cannot replicate God’s miraculous plague of lice, they give up. After that, the chartumim do not seem to be present at any other confrontational meetings between Moses and Pharaoh.7

But Pharaoh continues to assume that no matter what happens Egypt will go on, he will stay on the throne, and he must keep the Israelites as his slaves. Whenever Pharaoh’s faith is shaken, he recovers—until the final blow, the death of his own first-born son.

The longer you hold a belief, the harder it is to give up. What does it take before you admit you were wrong?

A single unexpected event, like the sight of a bush that burns but is not consumed?

Several demonstrations that the power structure you depend upon has been subverted?

The destruction of your world because of your failure to change?

- According to modern source criticism, a redactor of the book of Exodus patched in some material from a different account. The portion Shemot recorded mostly J and E traditions of the tale. Exodus 6:2-7:13 comes mostly from P sources, with some explanatory additions.

- The word tanin appears 14 timesin the Hebrew Bible. Half the time it means a sea-monster—or perhaps a crocodile (Genesis 1:21, Isaiah 27:1 and 51:9, Jeremiah 51:34, Psalms 74:13 and 148:7, Job 7:12, and Nehemiah 2:13). Twice a tanin is a snake (Deuteronomy 32:33 and Psalm 91:13), and twice it is a misspelling of “jackals” (tanim, in Lamentations 4:3 and Nehemiah 2:13). The remaining three occurrences of the word tanin are in the P story about the meeting with Pharaoh. (The word tanim, תַּנִּים, also occurs 14 times in the Hebrew Bible. In 10 of those occurrences it means “jackals”. But it is used as an alternate spelling of tanin in Isaiah 13:22 (snakes), Ezekiel 29:3 and 32:2 (crocodiles or sea monsters), and Psalm 44:20 (sea monsters).

- Prof. Scott B. Noegel, “The Egyptian ‘Magicians”, www.thetorah.com.

- One of the rituals in The Book of Overthrowing Apep, circa 305 B.C.E.

- Exodus 7:22 and 8:3.

- Exodus 8:14.

- No chartumim are mentioned in the passages about the next two plagues. The story of the sixth plague, boils, says: The chartumim were not able to stand in front of Moses because of the boils. (Exodus 9:11) After that they are absent from the rest of the book of Exodus.