“Redeeming” can mean exchanging something less important to you for something more important. Last week’s Torah portion, Behar, prescribed redemption for Israelites who had fallen into poverty and debt. If they were forced to sell the family farm, or if they had to sell themselves as slaves, the sale was never permanent; Israelite land was “sold” as a long-term lease, and Israelite persons were “sold” as indentured servants. Both land and human beings could be redeemed if a family member paid off the remainder of the contract. (See my post: Behar: Redeeming an Identity.)

“Redeeming” can also mean making good on a pledge, through either an exchange or a rescue. When a human being pledges a donation to God, they must give the donated item to the priests at the temple—or else redeem it by exchanging the pledged item for something more valuable. But when God makes a pledge to the Israelites, God makes good on the pledge by rescuing them from a foreign power. No exchange is necessary.

Bechukotai: When an Israelite redeems a pledge to God

A pledge to God is actually a pledge to support a religion’s service to God. Today someone who wants to make an extra donation to their congregation, over and above the membership dues, might send an electronic payment. But in ancient Judah, an extra donation, over and above the mandatory tithes, offerings, and contributions of firstborn animals and first fruits, could only be made by bringing an object of value to the priests at the temple in Jerusalem. So the donor would make a verbal pledge, and redeem it later by traveling to the temple and delivering either the item pledged or its value in silver.

The item pledged could even be a human being. The Talmud tractate Arakhin explains that a person often pledged his or her own value in silver to the temple in Jerusalem. But someone could also vow to donate the value of any person belonging to him or her at the time—i.e. someone the vower owned and could legally sell. In that era, people could sell their slaves or their own underage sons and daughters.

This week’s Torah portion, Bechukotai (Leviticus 26:3-27:34), explains the rules for redeeming a person who has been pledged as a donation to God.

When anyone explicitly vows the assessment of persons to God, the assessment will be: the assessment of the male from twenty to sixty years old will be fifty shekels of silver … (Leviticus 27:2-3)

A list follows giving the assessment in silver for male and female human beings in four age categories. (See my post: Bechukotai: Gender, Age, and Personal Value.) The persons themselves are not being given to God; they stand in as pledges until the donor pays their assessed values in silver to the temple.

But if [the donor vowed] an animal that can be brought as an offering to God, anything that he gives to God becomes consecrated. One may not replace or exchange it, either a better one for a worse one, or a worse one for a better one. And if one actually does exchange one animal for another, both it and its substitute will become consecrated. (Leviticus 27:9-10)

This means that when anyone pledges an animal that can be legally offered at the altar, it becomes temple property at that instant. The donor no longer owns it, so he has no choice but to bring it in to its rightful owner, the temple. If he tries to substitute a different animal, then both the original and the substitute must be brought and slaughtered for God. I suspect the priests knew that people who felt moved to give more to God sometimes had second thoughts later, and tried to skimp when it was time to fulfill their pledges.

If someone pledges an animal that is kosher, but unfit for the altar because of some blemish, the priest assesses its equivalent value. Then the person who pledged the animal to God must donate that amount in silver to the temple—and also leave the blemished but edible animal with the priests.

If the donor prefers to keep the unfit animal, he can redeem it by making a larger payment in silver.

But if definitely yigalenah, then he must add one-fifth to its assessment. (Leviticus 27:13)

yigalenah (יִגְאָלֶנָּה) = “he would redeem it”. (From the root verb ga-al, גָּאַל = redeem, ransom, rescue.)

The same law applies when a donor—perhaps overcome by religious ecstasy or a generous impulse—pledges his house to God, thus making it consecrated property.

And if the consecrator yigal his house, then he must add one-fifth in silver to the assessment; then it will be his. (Leviticus 27:15)

yigal (יִגְאַל) = he would redeem. (Also from the root verb ga-al.)

The donation of a field to God is more complicated, since the procedure must also meet the rules in last week’s Torah portion about land reverting to its original owner in the yoveil year. (See my post: Behar: Redeeming an Identity.) But if the current owner wants the field back before the yoveil year, he must pay silver equal to the assessment for the remaining years plus one-fifth to redeem it.

Va-eira & Second Isaiah: When God redeems a pledge to the Israelites

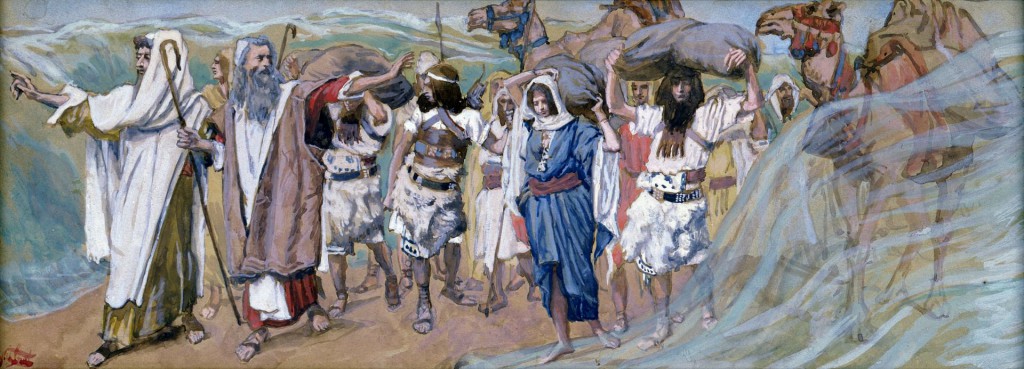

Israelites redeem their pledges to God by exchanging silver for whatever they pledged. But when God redeems a pledge to the Israelites, God simply rescues them by arranging their liberation from a foreign power and sending them “home” to Canaan. In the book of Exodus, God rescues the Israelites from bondage in Egypt. In the book of Isaiah, God rescues them from exile in Babylon.

In Exodus, in the Torah portion Va-eira1, God tells Moses:

“And now I myself have listened to the moaning of the Israelites because the Egyptians are enslaving them, and I have remembered my covenant. Therefore say to the Israelites: I am Y-H-V-H, and I will bring you out from under the bondage of Egypt. And I will rescue you from your servitude, vega-alti you with an outstretched arm and with great punishments. And I will take you as my people, and I will be your God. … And I will bring you to the land that I raised my hand to give to Abraham, to Isaac, and to Jacob, and I will give it to you as a possession. I am Y-H-V-H.” (Exodus 6:5-6, 6:8)

vega-alti(וְגָאַלתִּי) = and I will redeem, and I will rescue. (Also from the root ga-al.)

The pledge or covenant God made in the book of Genesis to Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob by “raising a hand” was that God would give their descendants the land of Canaan. Now God affirms that God will fulfill the pledge. Just as written proclamations in the Ancient Near East ended with the king identifying himself by name, God concludes this statement with I am Y-H-V-H, confirming it as a legal pledge.

Then God makes good on the divine pledge with an elaborate rescue operation. First God stages ten miracles to liberate those descendants, the Israelites, from Egypt. Then God leads them to a new home in Canaan.

Second Isaiah2 states that God created the Israelites for a unique role, which implies a pledge to make sure they continue to exist as a people on the land God chose for them.

And now thus said God:

Who created you, Jacob?

Who formed you, Israel?

Do not fear, because ge-altikha.

I have called by name;

You are mine. (Isaiah 43:1)

ge-altikha (גְאַלְתִּיךָ) = I have redeemed you, I have rescued you. (Also from the root ga-al.)

Therefore, the prophet says, God is in the process of rescuing the Israelites from Babylon by arranging the destruction of the Babylonian Empire.

Thus said God,

Your Go-eil, the Holy One of Israel:

For your sake I send to Babylon

And I bring down the bars, all of them,

And the Babylonians sing out in lamentations. (Isaiah 43:14)

go-eil (גֺּאֵל) = redeemer, rescuer. (Also from the root ga-al.)

This is one of eleven times that second Isaiah makes go-eil part of God’s title.3

The “bars” in this verse are either the bars of the gates of the city,4 or by extension, the borders of their whole territory.5 Second Isaiah credits God with sending Cyrus, the first king of the Persian Empire, to conquer Babylon6 (a feat Cyrus I achieved quickly in 539 B.C.E.).

Next the redemption of the Israelites from Babylon is connected with their redemption from Egypt. The prophet reminds us that God parted the Red Sea to arrange the escape of the Israelites from Pharaoh’s army of chariots.

Thus said God:

Who placed a road in the sea,

And a path through powerful waters?

Who met chariots and horses,

The mighty and the strong?

Together they lay down, never to rise;

They were extinguished, quenched like a wick. (Isaiah 43:16-17)

When second Isaiah is praying to God for redemption from Babylon, he reminds the exiled Israelites again about how God redeemed the Israelites from Egypt.7

Like other biblical prophets, second Isaiah says God let the Babylonians conquer Judah and Jerusalem because its citizens were disobeying God. But now, according to the book of Isaiah, God says:

I have wiped away your rebellions like fog,

And your misdeeds like cloud.

Return to me, because ge-altikha! (Isaiah 44:22)

Once God has redeemed the Israelites from their past sins, God can rescue them from Babylon. The book of Isaiah confirms that redemption by God is a rescue, not an exchange:

For no price you were sold,

And not for silver tiga-eilu. (Isaiah 52:3)

tiga-eilu (תִּגָּאֵלוּ) = you will be redeemed.

But being rescued and liberated is not enough. The Israelites must fall in with God’s plan by taking advantage of the opportunity to leave Babylon and return to Jerusalem.

Go forth from Babylon!

Flee from Chaldea!

Declare in a loud voice,

Make this heard,

Bring it out to the ends of the earth!

Say: God ga-al [God’s] servant Jacob! (Isaiah 48:20)

The kind of exchange outlined in this week’s Torah portion, Bechukotai, is good business practice: making a pledge, posting something as security, and then redeeming the security by handing over the required monetary payment. Both the donor and the priests who receive the silver know and follow the rules.

But sometimes we humans imitate God by pledging to do something that has no monetary value. One example is the traditional marriage vow to “forsake all others”.

And sometimes we help another person voluntarily, for no reward, with no expectation of tit-for-tat—not because we have formally pledged to do so, but just out of the goodness of our hearts.

All humans make moral errors. When we do something good, above and beyond what we have promised, we redeem ourselves. So helping someone out of the goodness of our hearts is a double redemption: we rescue the other person from distress, and we also redeem ourselves.

May we all aspire to be voluntary redeemers.

- The portion Va-eira is Exodus 6:2-9:34.

- The first 39 chapters of the book of Isaiah were written in the 8th century B.C.E., and are attributed in the first verse to the prophet Yesheyahu (Isaiah) son of Amotz. Chapters 40-55 were written in the 6th century B.C.E., after the Babylonians conquered Jerusalem and deported its leading citizens to Babylon; this section is often called Second Isaiah or Deutero-Isaiah. Chapters 56-66 were written after Babylon fell to the Persian Empire in 539 B.C.E. and the exiles living there were allowed to return to their old homes. Some scholars include this last section in Second Isaiah, while others call it Third Isaiah, or Trito-Isaiah.

- Go-eil is part of God’s title in Isaiah 41:14, 43:14, 44:6, 44:24, 47:4, 48:17, 49:7, 49:26, 54:8, 60:16, and 63:16.

- Ibn Ezra (12th century), citing Lamentations 2:9: Her gates have sunk into the ground, He has shattered to bits her bars.

- Adin Steinsaltz, The Steinsaltz Humash: Isaiah, Koren Publishers, 2019.

- See Isaiah 44:1.

- Isaiah 51:10-11.