Last week’s Torah portion, Yitro, begins with the reunion of Moses and his father-in-law, then moves into the mind-bending revelation of God at Mount Sinai. This week’s Torah portion, Mishpatim (Laws) gives a long list of laws, then ends with a vision of God’s feet on a sapphire pavement. (See my blog “Mishpatim: After the Vision, Eat Something”.)

I’m always tempted to rush straight from the vision of God as fire and thunder to the vision of God’s feet. But imagine someone who had two mystical experiences in a row, with no time in between to come down to earth. Their mental balance would be hard to recover. It would actually be a blessing to spend an interval on practical matters, in between mystical experiences. Maybe reading case law in between the stories of visions at Mount Sinai serves an analogous purpose for Torah scholars.

So this year I paid attention to the case law, and found one law that might addresses unbalancing mental states.

If a fire goes forth, and it finds thorn-bushes, a heap of grain or the standing grain, or the field, and they are consumed, the burner who starts the burning shall certainly make complete restitution. (Exodus/Shemot 22:5)

On a peshat (simple) level, this law refers to legal responsibility for negligence in a certain farming practice. On the next level of traditional Torah interpretation, remez (alluded extension), the Talmud tractate Baba Kama (60a) treats this law as a paradigm for all cases in which someone deploys a fire, an animal, a tool, or anything that is not fixed in place, and then it causes damage because the person did not keep it under control.

Going up another rung, at the level of drash (investigation), I see that the law embodies two ethical principles: that we should make every effort to avoid doing any harm through negligence; and that if it happens anyway, we must make restitution.

At the fourth level of Torah interpretation, sod (secrecy, intimacy), the verse speaks to our own psychological and spiritual condition. In the Torah, as in colloquial English, fire and burning are often used to describe human passions such as anger, or lust, or even an overwhelming longing for God. Any consuming passion is likely to get out of control. Unless people in the throes of passion pay attention and take special care, their negligence can result in significant damage, both to themselves and to others.

Let’s look at the verse again, to see what the fire of passion might consume.

If a fire goes forth, and it finds thorn-bushes, a stack of grain or the standing grain, or the field, and they are consumed, the burner who starts the burning shall certainly make complete restitution.

kotzim = thorn-bushes, thorns. (A verb with the same root is kutz = awaken; feel sick and tired of.)

gadish = a stack or heap of grain.

hakamah = the standing. (Standing grain is implied in a simple reading of the verse.)

hasadeh = the field (cultivated or open); the plot of land owned by an individual; the domain of a city.

bo-eirah = burning, kindling or maintaining a fire; sweeping away; being stupid as a cow.

In a reading at the sod level, if a fiery passion is not guarded, it first consumes thorn-bushes. Applied to your own soul, the burning anger or desire is at first beneficial, eating up those annoying, thorny habits of thought that you are sick and tired of. Your passion is so strong, it sweeps aside the inner voice that keeps saying “You’re not good enough”, or the one that always says, “It’ll never work”, or—well, we each have our own mental habits. When a passion sweeps them away, it feel as if you are waking up to a new and better self.

But your consuming passion also burns up the people around you who are thorns in our sides, the people whom you are sick and tired of. Speaking from rage, or passionate conviction, or overwhelming desire, you impatiently mow right over the people you find difficult. In the long run, this is not beneficial to either you or them.

Next, your inner conflagration burns up the grain you have cut and stacked for future nourishment. In the heat of the moment, preserving the other aspects of your life seems unimportant. All that matters is the pursuit of the object of your anger or desire. Yet if you are not careful, you can damage a relationship or a job or even your own body.

After that, the fire can destroy your own standing—both your reputation, and your uprightness or moral compass. It is tempting, in the heat of passion, to cross lines you would never cross in your cooler moments. And with uncontrolled, passionate speech, you may also destroy the reputation of others, or incite them to react in a way that they will feel guilty about later.

Finally, if your passion continues unchecked, you will cross the line in another way, failing to respect the boundary between yourself and another human being. The whole word looks as if it is lit with fire, so it all appears to be part of the same passion that is consuming you. Of course the person you are talking to feels the same way you do! Of course they want the same things! Of course they will do exactly what you want! Of course they will be happy if you make it easier for them to do what you want by interfering with their lives!

Most of us know about the hazards of unchecked anger or lust. Most of us do not want to be negligent when these passions seize us. We work on paying attention and controlling ourselves.

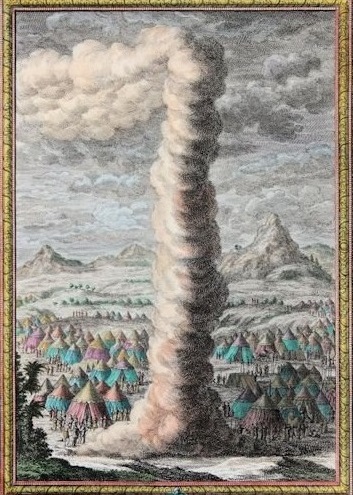

But the Torah focuses most often on the passionate desire for God, which rises like a flame. And the Torah’s most common metaphor for God is fire. Sometimes God manifests as a fire that does not consume, like the one Moses saw in the burning bush (which, by the way, was not a thorn-bush). But often God manifests in the Torah as a fire that does consume, and sometimes kills.

When we are filled with a passion that seems as if it comes from God, because we are burning for justice, or for a religious experience, that is when we are most in danger of being negligent and causing unforeseen damage to ourselves and others.

The law in this week’s Torah portion rules that the person who starts a fire and fails to control it must make complete restitution for all damages. But some damage cannot be repaired.

May each of us be blessed with the ability to pay attention when we feel any passion, even the most righteous passion, begin to consume us; to remain aware of everything we would normally consider; and to control our speech and our actions so we do no harm. May we burn brightly without consuming, and without being stupid as a cow.