(One of a series of posts comparing ideas in the book of Exodus/Shemot with related ideas in the book of Psalms.)

Us and them. Citizens and foreigners. Friends and enemies.

Human nature always divides members of our species into two or more groups. But how we treat the “out” group depends on our ethical, religious, and political rules.

This week’s Torah portion, Mishpatim (“Laws”), is set at Mt. Sinai, long before the Israelites conquer part of Canaan and set up their own government. But it includes a series of laws written after the kingdoms of Israel and Judah were founded. One of the subjects these laws address is how to treat immigrants and conquered natives.

A geir you shall not cheat nor oppress, since you were geirim in the land of Egypt. (Exodus/Shemot 22:20)

geir (גֵר) = foreigner, stranger, resident alien, sojourner, immigrant, non-citizen. From the root verb gar (גָּר) = sojourned, stayed with, resided with.

geirim (גֵרִים) = Plural of geir.

(The meaning of geir shifted in Jewish writings after 100 C.E., coming to mean a proselyte or convert.)

After a few more laws, the Torah portion Mishpatim adds:

And a geir you shall not oppress, for you yourselves know the feelings of the geir, since you were geirim in the land of Egypt. (Exodus/Shemot 23:9)

Unlike foreigners who are merely visiting another country, geirim are displaced persons who cannot call on their former clan chiefs (or national governments) for protection. They are at the mercy of the country where they now live, subject to the whims of its ruler and its wealthy citizens. Unless their new host country protects them, they are subject to deportation even when they no longer have a home to return to (like resident aliens in the United States today), or to slavery (like the Israelites in Egypt at the beginning of the book of Exodus).

This week’s Torah portion gives one example of not oppressing a geir who works for you:

Six days you shall do your doings, but on the seventh day you shall stop, so that your ox and your donkey shall rest, and the son of your slave woman and the geir shall refresh their souls. (Exodus 23:12)

by R.F. Babcock

The Hebrew Bible includes many further injunctions to treat geirim with consideration.1 In summary, if geirim are servants of Israelites, they must get the same holiday feasts and days off as native slaves or servants. If geirim are hired laborers, they must be paid daily, like Israelite laborers. If geirim are not attached to an Israelite household and are impoverished, they get the same rights as impoverished citizens. Geirim are even urged to flee to the same cities of refuge if they are unjustly accused of murder.

Since the kingdoms of Israel and Judah are theocracies, treating their geirim like citizens also means the geirim must conform at least outwardly to Israelite religious life, and suffer the same punishments for transgressions.2

However, two kinds of discrimination against geirim are sanctioned in the Torah: an Israelite may not charge interest on a loan to a kinsman, but may charge interest on a loan to a geir 3; and while an Israelite can always redeem a kinsman from slavery by paying the slave’s owner, a geir has no such right.4

Nevertheless, the Bible urges the Israelites to love the geirim living in their land.5

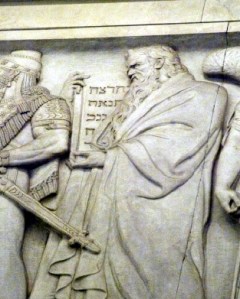

Mt. Eival right.

In three books of the Bible, resident geirim are even included in the covenant with God.6 One example is when Joshua enters Canaan and enacts a ritual of covenant at Mt. Eival.

All Israel—its elders, its officials, and its judges—were standing on either side of the ark, facing the priests of the Levites, carriers of the ark of the covenant of God—the geir the same as the native. (Joshua 8:33)

(In this case, “native” (ezrach, אֶזְרָח) means someone of Israelite ancestry, since both the Israelites and their fellow travelers are newcomers to Canaan.)

Another example is when the prophet Ezekiel predicts a new covenant with God once the Israelite deportees in Babylon move back to their old land. In this covenant, people who were once geirim become citizens of the tribes they lived with.

You shall divide up this land for yourselves among the tribes of Israel. And you shall cast [lots] for hereditary possessions, for yourselves and for the geirim who are garim among you … And the geir will be in the tribe that gar with; there you will give him his hereditary possession—declares my Master, God. (Ezekiel 47:21-23)

garim (גָּרִים) = sojourning, staying with, residing with as foreigners. (From the root verb gar.)

gar (גָּר) = he sojourned, stayed with, resided with.

All these rules ensuring fairness to the geirim would not have been written unless some native Israelites were mistreating resident aliens. The Torah correctly points out that the geirim are vulnerable outsiders, just as the Israelites were once vulnerable outsiders in Egypt.

*

Psalms 39 and 119 take the idea of the geir to the next level. If non-citizens are vulnerable in the country where they live, then perhaps humans are vulnerable before God, whose ways are mysterious.

Psalm 39 introduces a speaker who is worried about the shortness of his life. He alludes to a scourge from God, probably an illness. The psalm concludes:

And listen to my cry for help!

Do not be silent to my tears.

For I am a geir with You,

A resident alien, like all my forefathers.

Look away from me, and I will recover,

Before I depart and I am not. (Psalm 39:13-14)

Like a geir, this psalmist feels vulnerable and uncertain of God’s ultimate protection. Instead of asking God to intervene, he begs God to ignore him so he can at least enjoy the remainder of his short life. A geir does not dare to ask for too much.

*

Psalm 119, written during the time of the second temple, is the longest in the book of Psalms. Its 176 verses begin with letters of the alphabet from alef to tav, the equivalent of the English A to Z. There are eight verses for each letter, and all are variations on the theme of praying to God for help in learning and understanding God’s laws. The verses that begin with the letter gimmel (ג) open with:

Finish maturing (גְּמֺל) Your servant! I will live and I will observe Your word.

Uncover (גַּל) my eyes, and I will look upon the wonders of Your teaching.

A geir (גֵּר) I am in the land; do not hide from me Your commands.

My soul pines away (גָּרְסָה), longing for Your laws at all times. (Psalm 119:17-20)

The psalmist expresses the feeling of being a vulnerable outsider who does not understand what is really going on. Anyone who seeks to serve a God who has issued hundreds of laws yet remains inscrutable feels like a geir. The overall theme of Psalm 119 is the longing to understand what God wants—which is like the longing of geirim to understand how things work in the strange country where they now live.

*

I appreciate how the Torah insists we must treat non-citizens with fairness and consideration, and reminds us that we have all been geirim at some time. Even if we have enjoyed the rights of the innermost in-group of native citizens our whole lives, we are still geirim with God.

And even within our own social circles, we get along better if we keep working to understand what our friends are really saying, how the world really looks to them. Ultimately, each of us is a geir with every other person, as well as with God—and perhaps even with ourselves.

—

1 Enjoying Shabbat and holidays: Exodus 12:19, 12:48, 20:10, 23:12; Numbers 35:15; Deuteronomy 5:14, 16:14, 26:11-13.

Receiving wages promptly: Deuteronomy 24:14.

Receiving assistance like the native poor: Geirim are usually listed along with widows and fatherless children as entitled to glean produce from private fields, orchards and vineyards (Leviticus 19:10, 23:22; Deuteronomy 21:20, 24:17, 24:19, 24:20; also see Ruth ch. 2); to take home a share of the tithe for the poor (Deuteronomy 14:28-29); and to receive just redress (Deuteronomy 24:14; Jeremiah 7:6, 22:3; Zechariah 7:10; Malachi 3:5).

Using cities of refuge: Joshua 20:9.

2 Observing the native religion: Both citizens and geirim must fast on Yom Kippur (Leviticus 16:29), bring their burnt offerings to the alter of the God of Israel (Leviticus 17:8-9, 22:18), refrain from eating blood (Leviticus 17:10, 17:13), obey Israelite laws about permitted sexual partners (Leviticus 18:26), avoid taking God’s name in vain (Leviticus 24:16), and refrain from worshiping idols (Leviticus 20:2; Numbers 15:26, 15:29, 15:30, 19:10; Ezekiel 14:7).

3 Paying interest: Leviticus 25:35.

4 Lacking the right of redemption: Leviticus 25:35-36.

5 Being loved: Leviticus 19:33-34; Deuteronomy 10:18-19, 24:14.

6 Being included in the covenant: Deuteronomy 29:9-11, 31:12; Joshua 8:33, 8:35; Ezekiel 47:21-23.