(This is my twelfth and final post in a series about the evolving relationship between Moses and God in the book of Exodus/Shemot. Next week’s post will be back in sync with the Jewish weekly readings. Meanwhile, this is Passover week! If you’d like to read one of my posts on Passover, you might try: Pesach & Vayikra: Holy Matzah.)

Moses: from fearful loner to authoritative leader

When Moses walks over to look at the bush that burns but is not consumed, he is a curious man who has compassion for the victims of bullies,1 but he also has a history of anxiety. After a problematic childhood as an Israelite who was adopted by Egyptian royalty, he fled a murder charge in Egypt, then found a home with a Midianite priest. Safe but still wary, the last thing Moses wants to do is return to Egypt.

Then God speaks to him out of the fire, and Moses hides his face. (See my post: Shemot: A Close Look at the Burning Bush.) God tells him that he will be the human leader of the victimized Israelites in Egypt; Moses must give the pharaoh ultimatums, then conduct the people from Egypt to Canaan.

Moses tries to excuse himself from the job. He is certain that he is not qualified (see my post: Shemot: Empathy, Fear, and Humility); that the Israelites will not believe or trust him (see my post: Shemot: Names and Miracles); and that he cannot speak well (see my post: Shemot: Not a Man of Words). But God patiently answers his every objection, like a parent with a resistant child. Panicked, Moses begs God to send someone else. God coaxes Moses into cooperating by promising that his long-lost brother Aaron will help him (see my post: Moses Gives Up).

Back in Egypt, Moses gradually changes. During his first few negotiations with the pharaoh, he simply parrots the words God gives him, but as his confidence grows he adds words of his own. It helps that a powerful deity backs him up with miraculous plagues, and it helps that the pharaoh and his court treat Moses with increasing respect. (See my post: Shemot to Bo: Moses Finds His Voice.)

When he leads the Israelites across the wilderness to Mount Sinai, they are the ones who behaved like wayward and frightened children. Moses behaves like a nervous new parent. He asks God, his mentor, for advice, but he also acts on his own initiative. (See my posts: Beshalach: Moses Graduates and Yitro: Moses as Middle Manager.)

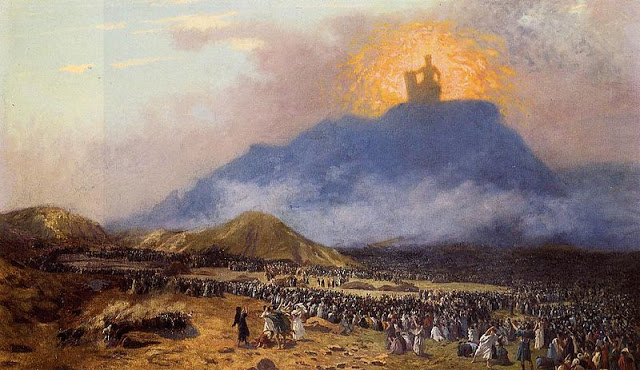

At Mount Sinai, God pursues a formal covenant with the Israelite people. Between them, God and Moses arrange a covenant four times. (See my post: Yitro & Mishpatim: Four Attempts at a Lasting Covenant.) The third of the four covenants is entirely Moses’ creation, and includes all of the people in a dramatic ritual with standing stones, animal sacrifices, blood splashing, and a public reading of the laws God has told Moses so far. The fourth covenant, God’s idea, is when the elders behold God’s “feet” and hold a feast (the Ancient Near East equivalent of a signing ceremony for a treaty).

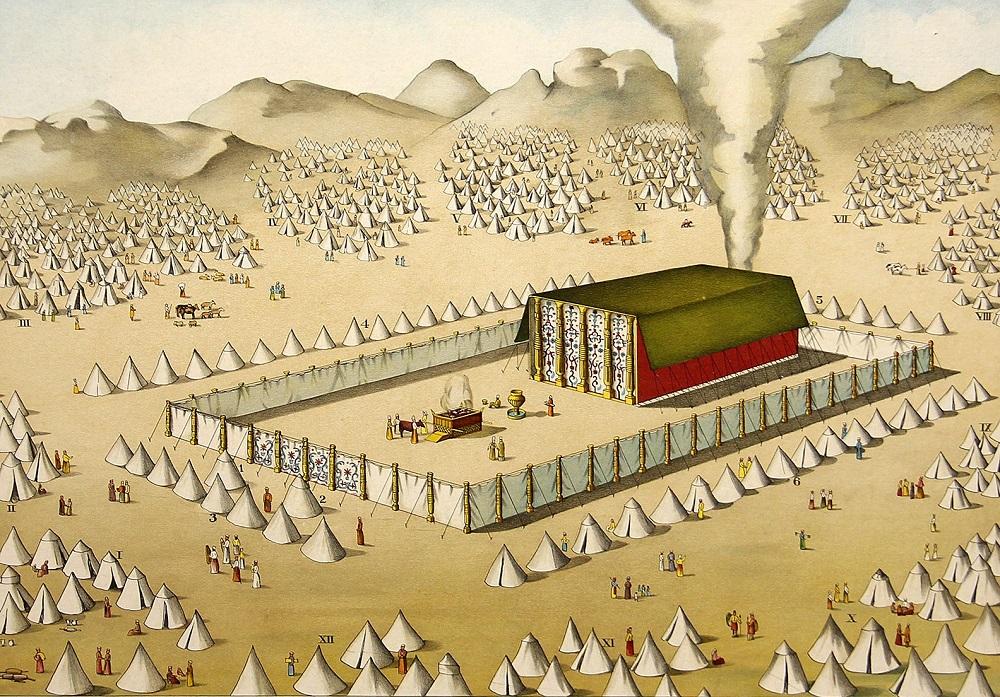

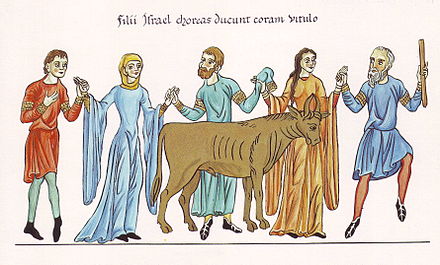

Then Moses spends 40 days on the mountaintop listening to God outline a revamped religion, which includes a sanctuary tent where God will dwell in the midst of the people. But the Israelites below think Moses will never return, and they ask Aaron for an idol to follow instead. Aaron makes the Golden Calf, and the people worship it—a clear violation of the covenant with God.

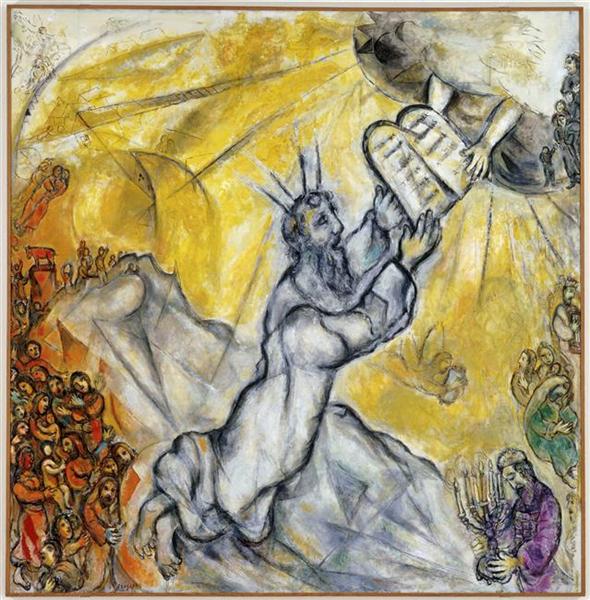

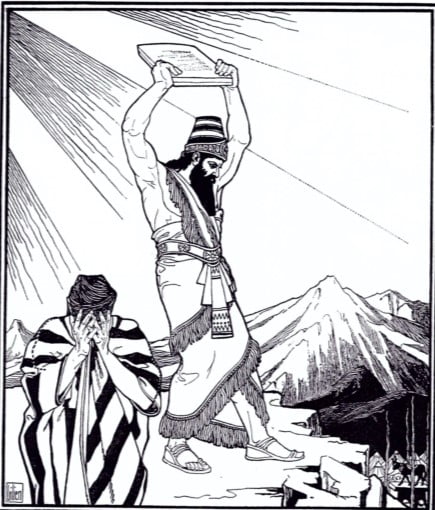

On the 40th day God offers to exterminate the people and start over with Moses’ descendants, but Moses passes God’s test and remains loyal to the Israelites. He walks down to the camp and smashes the two stone tablets engraved by God, but God recognizes Moses’ right to make decisions and takes no action. (See my post: Ki Tisa: Taking Risks.) The co-leaders arrange a massacre and a plague that kill the worst Golden Calf worshippers.

Then God tells Moses that a messenger will lead the Israelites to Canaan, because God is too angry to go in their midst. Moses presses God to reverse that decision, and also to pardon all the surviving Israelites. God seems favorable toward both requests, but never makes an explicit commitment. (See my post: Ki Tisa: Seeking A Pardon.) A lack of openness between the two leaders of the Israelites continues through the book of Numbers, with Moses pitching arguments designed to flatter and influence God, and God making decisions that are close to what Moses requests but not exactly the same.2

The story about Moses’ second 40-day stint at the top of Mount Sinai illustrates that the working relationship between the two leaders is not the only thing that changes.

Moses and God: shifting commitments

At the burning bush, God was determined to rescue the Israelites from Egypt and give them the land of Canaan. Moses tried to get out of being personally involved, even though he was empathetic toward all victims of bullies.

By the time Moses leads the Israelites to Mount Sinai, he has unreservedly embraced the mission God gave him, and he would do anything to make sure the Israelites as a people get to Canaan, even if individual Israelites have to die along the way. So after the Golden Calf worship, he focuses on restoring good relations between God and the people.

But God views the Golden Calf as a personal rejection, and seems less committed to the Israelites after that episode. God starts calling the Israelites Moses’ people, and shies away from recommitting to God’s earlier plan to dwell among them in the sanctuary tent.3 Twice in the book of Numbers, God threatens to wipe out all the Israelites.4

The God character: a new development

Nevertheless, when Moses asks to see God’s “ways”, “glory”, and “face”,5 God shows him what Jews now call “The Thirteen Attributes of Mercy”, including compassion, patience, loyal-kindness, and a willingness to exonerate (some of) the guilty.6 Although God continues to smite people in sudden fury from time to time, this description of God indicates a change in the God character that was depicted earlier in the Torah.

And right after the revelation of the Thirteen Attributes, when Moses begs God once more to pardon the people, God says:

“Hey, I am cutting a covenant: In front of all your people I will do wonders that have not been created on all the earth and among all the nations. And all the people in whose midst you are, they will see the doing of Y-H-V-H, how awesome it is what I do with you.” (Exodus 34:10)

The only awesome deed God mentions is driving out the six peoples living in Canaan when the Israelites arrive there. This is a promise that God will “give” them the land of Canaan, even though God is still calling them “your people” (Moses’ people) instead of “my people”. In return, the Israelites must refrain from making idols or bowing down to any other god and reject the gods of Canaan by destroying their objects of worship. They must also refuse to make covenants with the natives of Canaan, and avoid intermarriage with them. Then God throws in some of the earlier rules about observing religious holidays and donating firstborn animals and first fruits to God.

Then Y-H-V-H said to Moses: “Write these words for yourself, because according to these words, I cut a covenant with you and with Israel.” (Exodus 34:27)

So even if God does not explicitly pardon the people, as Moses asked, God is now patient and loyal enough to propose another covenant.

Moses: an apotheosis?

The experience of beholding God’s attributes also changes Moses in ways that might be considered an apotheosis: deification or elevation to divine status.

And he was there with Y-H-V-H forty days and forty nights. Bread he did not eat, and water he did not drink. And [God] engraved on the tablets the words of the covenant, the Ten Words. (Exodus 34:28)

Exodus does not say whether Moses went without food or drink the first time he spent 40 days at the top of Mount Sinai, though it is hard to imagine him trudging up to the barren volcanic mountaintop carrying enough food and water on his back to last 40 days. But Exodus does say that Moses lives without eating or drinking during his second 40-day stint.7

Shemot Rabbah explained: “What, then, did he eat? He was sustained by the aura of the Divine Presence. Do not wonder, as the heavenly beasts that bear the Throne are sustained by the aura of the Divine Presence.”8 This makes Moses like the serafim in Isaiah’s vision or the divine creatures in Ezekiel’s vision, at least temporarily.9

Rabbeinu Bachya wrote: “Moses’ nourishment during these forty days was provided by the attribute חסד and the radiation of supernatural light.”10 Chesed, חסד, is the “loyal-kindness” in God’s thirteen attributes. This commentary implies that God’s new gentle and compassionate approach sustains Moses so that he can live on the supernatural equivalent of light.

At the end of Moses’ first 40-day stint on the mountaintop, God gave him a pair of stone tablets that were already engraved. These were the tablets that Moses smashed at the foot of the mountain when he saw the ecstatic worship of the Golden Calf. For Moses’ second 40-day stint, God tells him to hew out his own stone blanks and carry them up.11 Then God engraves them after revealing the Thirteen Attributes. Moses may even see the words appearing on the stones.

And it was, when Moses came down from Mount Sinai—and the two tablets of testimony were in Moses’ hand when he came down from Mount Sinai—then Moses did not know that the skin of his face karan because of [God’s] speech with him. (Exodus 34:29)

karan (קָרַן) = shone, was radiant.

This verb has the same root as keren (קֶרֶן ) = horn, ray of light. (The Latin translation of this verse in the Vulgate said Moses “sprouted horns”, so for centuries artists depicted Moses with two horns growing from his forehead.)

What makes Moses’ formerly ordinary face start radiating beams of light? The text says it happens because of God’s “speech with him”. Many Jewish commentators wrote that it happens when God reveals the Thirteen Attributes of Mercy to Moses. God said:

“… as my glory passes by, I will place you in a crevice of the rock, and screen you with my hand until I have passed by. Then I will take away my hand, and you will see the back side of me. But my face will not be seen.” (Exodus 33:22-23)

The “back side” of God that Moses “sees” consists of the Thirteen Attributes. Either God’s supernatural hand,12 or the experience of these divine attributes,13 gives Moses an inner light so strong that it shines out through the skin of his face.

On the other hand, some commentators wrote that God gives Moses a radiant face as a strategic move to make sure the Israelites continue to accept him as their leader. The 13th-century commentary Chizkuni says:

“Seeing that prior to Moses’ return with the first set of Tablets the people had been prepared to accept another leader in Moses’ place, his emitting rays of light on his descent from the Mountain this time made a repetition of such an attempt quite unlikely.”14

And Aaron and all the Israelites saw Moses, and hey! The skin of his face karan! And they were afraid to come near him. (Exodus 34:30)

Chizkuni explained: “According to the plain meaning of the verse, when they beheld him, they thought that they were looking at an angel.”15

And Robert Alter wrote: “If, as seems likely, Moses’ face is giving off some sort of supernatural radiance, the fear of drawing near him precisely parallels the people’s fear of drawing near the fiery presence of God on the mountaintop.”16

Moses himself is not aware that his own face was radiating light, according to the 18th-century commentary Or HaChayim, because he assumes that the extra illumination came from the second pair of stone tablets he is holding as he walks down the mountain. “As soon as he deposited the Tablets and he became aware that the light had not departed, he realised that he himself was the source of the light.”17

Then Moses called to them, and Aaron and all the chiefs in the congregation returned, and Moses spoke to them. And after that, all the Israelites approached, and he commanded them everything that Y-H-V-H had spoken to him on Mount Sinai. (Exodus 34:31-32)

According to Chizkuni, just hearing Moses’ voice calling out was enough so that “they realized that he was not an angel”. Then when Moses spoke to Aaron and the chiefs, the rest of the Israelites “noticed that no harm had come to them from his speaking to them.”18

And Moses finished speaking with them, and he put a veil over his face. And whenever Moses came before Y-H-V-H to speak with [God], he would remove the veil until he went out. And [whenever] he went out to speak with the Israelites what he had been commanded, the Israelites would see Moses’ face, that skin of his face was karan. Then Moses would put back the veil over this face, until he came in to speak with [God]. (Exodus 34:33-35)

Moses exposes his altered face to God, and he to the Israelites whenever he is telling them the latest batch of rules from God. Who would question the words of someone whose face emits supernatural light? But the rest of the time when he is with people, Moses covers his face with a light-proof veil.

According to Rashi and Ibn Ezra, Moses puts on the veil out of respect for the light God has created on his face; it is not for ordinary use, or for people to gawk at. People should only see it when he is transmitting God’s instructions. According to Kli Yakar, “Moshe, in his great humility, was embarrassed when people gaped at the radiance of his face.”19

It seems as if God has turned Moses into a semi-divine being. He lives for 40 days on the aura of God’s presence, like God’s divine attendants. When he comes down from Mount Sinai, God’s supernatural fire shines through the skin of his face. Moses might look like one of the gods of other peoples in the Ancient Near East, who radiated an unearthly light called melammu. For example, a story about the Babylonian god Marduk says “With burning flame he filled his body” and “With overpowering brightness his head was crowned.”20 The gods in Mesopotamian myths sometimes gave melammu to their favorite kings.

Or perhaps (if he took off his robe) Moses would look like the celestial being shaped like a man whom Daniel sees in a vision sent by Y-H-V-H:

His body was like yellow jasper, and his face had the appearance of lightning, and his eyes were like torches of fire, and his arms and legs were like glittering bronze, and the sound of his speech was like a roaring crowd. (Daniel 10:6)

But in the Hebrew Bible, the various angelic creatures in the bible are either mouthpieces for God or manifestations of God’s powers, without lives of their own.

Perhaps that is why Moses’ radiant face appears only in Exodus 34:29-35. The authors of the rest of the Torah chose to depict Moses as a human being—one who is especially close to God, but a mortal man with his own thoughts and personality.

In the next chapter of Exodus, Moses proceeds with God’s earlier plan for building a tent-sanctuary, as if God had never refused to dwell in the midst of the Israelites. And God does not challenge Moses’ stubborn human initiative.

When Moses is 120 years old and has finished speaking to the Israelites on the Moabite bank of the Jordan River, God tells him to climb up the heights of Aviram and look across the river at the land of Canaan. God says:

So, after delivering a prophecy about the tribes, Moses hikes up.

“You will die on the mountain where you are going up … because at a distance you will see the land, but you will not enter there, into the land that I am giving the Israelites.” (Deuteronomy 32:50, 52)

And Moses, the servant of Y-H-V-H, died there in the land of Moab, al-pi Y-H-V-H. And [God] buried him in the valley in the land of Moab … and no man knows his burial place to this day. (Deuteronomy 34:5-6)

al-pi (עַל־פִּי) = an idiom meaning at the order of, at the command of, according to the word of. Literally: al (עַל) = upon, over, on account of, because of, by. + pi (פִּי) = mouth of.

Some commentators translate al-pi as “by the mouth of”, and say that Moses dies by a kiss from God.21 So although Moses is not permanently transformed into a semi-divine being, he has the the most intimate human relationship with God.

And no prophet arose again in Israel like Moses, whom Y-H-V-H knew face to face. (Exodus 34:10)

- Moses has already taken action against an Egyptian taskmaster beating an Israelite (Exodus 2:11-12) and male shepherds bullying female shepherds (Exodus 2:16-19). See my post: Shemot: Empathy, Fear, and Humility.

- E.g. Numbers 14:11-35.

- See my post: Ki Tisa: Seeking A Pardon.

- Numbers 14:11-12, 17:8-9.

- Exodus 33:13, 33:18, 33:20. See my post: Ki Tisa: Seeking A Pardon.

- Exodus 34:6-7.

- At least this is the second time Exodus says Moses spends 40 days and 40 nights on the mountaintop. But some classic commentators claimed it was the third time, the second time being the indefinite period when God and Moses converse in Exodus 33:12-34:3.

- Shemot Rabbah, 12th century, translation in www.sefaria.org.

- Isaiah 6:2-7, Ezekiel 1:5-26 and 10:1-22.

- Rabbeinu Bachya (Rabbi Bachya ben Asher ibn Halawaa, 1255-1340), translation in www.sefaria.org.

- Exodus 34:1.

- E.g. Midrash Tanchuma (8th century), Rashi (11th-century Rabbi Shlomoh Yitzchaki), and Da-at Zekinim (12th-13th century).

- E.g. Ibn Ezra (12th century) and Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz (21st century).

- Chizkuni, by Chizkiah ben Manoach, 13th century, translation in www.sefaria.org.

- Chizkuni, ibid.

- Robert Alter, The Five Books of Moses, W.W. Norton & Co., New York, 2004, p. 512.

- Or HaChayim, by Chayim ibn Attar, 18th century, translation in www.sefaria.org.

- Chizkuni, ibid.

- Kli Yakar, by Shlomo Ephraim ben Aaron Luntschitz, 16th century; translation in www.sefaria.org.

- Enuma Elish IV, lines 40 and 58; translation by L.W. King.

- E.g. Talmud Bavli, Moed Katan 28a, Bava Batra 17a; Rashi; Da-at Zekinim.