As a child I was a natural victim, the target of any bully who needed to humiliate someone. So I can imagine how the Israelites might feel in the book of Exodus/Shemot when they finally leave Egypt on the morning after God’s tenth and final plague:

Our god beat the pharaoh! We asked our Egyptian neighbors for silver and gold, and they just handed it over to us! Yesterday we were slaves, and today we are free! We can do what we please, and we never need to be afraid of Egypt again!

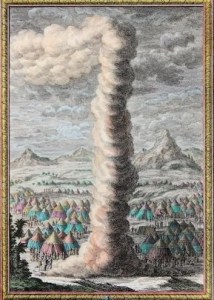

The Israelites leave the city of Ramses unchallenged at the beginning of this week’s Torah portion, Beshalach (“When sending out”). They march for three days in military formation, following God’s spectacular pillar of cloud by day and fire by night. For three days, they feel on top of the world.

God leads them to the Reed Sea, rather than by the main road to Canaan, which passes through the land of the Philistines.1 When the Israelites reach the shore of the Reed Sea, God stages one last showdown with the pharaoh.

God strengthened the heart of the pharaoh, the king of Egypt, and he chased after the children of Israel, while the children of Israel were going out beyad ramah. (Exodus 14:8)

beyad ramah (בְּיָד רָמָה) = with a high hand. Yad (יָד) = hand; power to do something. Ramah (רָמָה) = high, exalted.

What does it mean to march “with a high hand”? When I first read this passage, I pictured the Israelites raising their hands as if they were trying to get the teacher’s attention. But this image is the opposite of the spirit of beyad ramah.

In both Biblical Hebrew and English, the word yad or “hand” is used in many idioms. After all, we accomplish things primarily with our hands. Twice in the Torah portion Beshallach Moses raises his hands in order to channel divine energy. At the Reed Sea, God tells Moses:

And you shall be hareim your staff and stretching out your yad over the sea and splitting it, and the Children of Israel shall come into the middle of the sea on dry land. (Exodus 14:16)

hareim (הָרֵם) = raising, lifting up. (From the same root as the adjective ramah.)

Later in this week’s Torah portion the people of Amaleik attack the Israelites, and Moses influences the course of the battle by stationing himself on a hill and raising his hands.

And it happened that Moses yarim his yad, then Israel was mightier, but when he rested his yad, then Amaleik was mightier. (Exodus 17:11)

yarim (יָרִים) = he would raise. (From the same root as ramah.)

The Israelites win the battle because Aaron and Hur help Moses hold up his hands when he gets tired. This confirms that holding up his hands is how Moses channels God’s power; he does not have power of his own.

But the idiom yad ramah refers to acting as if you have power to accomplish things by yourself. It appears only four times in the Torah, and two of these appearances refer to the way the Israelites leave Egypt (in Exodus 14:8 above, and in Numbers/Bamidbar 33:3). The other two appearances help to clarify the idiom’s meaning.

But a person who does it beyad ramah, whether citizen or foreign resident, is reviling God; so that person will be cut off from among the people. (Numbers 15:30)

In this passage, the Torah has just ruled that if someone inadvertently fails to obey one of God’s laws, he can atone by offering a goat as a sacrifice. But if he does it on purpose, acting “with a high hand”, the consequence is more severe: he is banished or dies. When someone transgresses deliberately, beyad ramah, he is acting as if he has more authority than the religious law.

The fourth occurrence of yad ramah in the Torah comes in Moses’ parting poem to the Israelites. In his long final warning, Moses quotes God’s response to their ingratitude and idolatry:

I said: I would have cut them to pieces,

I would have made the memory of them disappear from men,

If I had not feared for the provocation of enemies—

lest their foes would misinterpret,

lest they would say: “Our yad was ramah, and it was not God Who accomplished all this!”

(Deuteronomy/Devarim 32:26-27)

Here, the “high hand” is the arrogance of Israel’s enemies, who will falsely assume that they have the power to destroy Israel on their own, without God’s collaboration.

Similarly, in English “high-handed” persons assume they have all the power, and arrogantly do something without considering the concerns of others.

So why do the newly freed slaves in the portion Beshalach leave Egypt beyad ramah? Dazzled by their new higher status, they may well imitate the arrogance of their former masters. If they had a chance, they might even try to bully or enslave someone less fortunate. But God does not give them a chance.

In this week’s Torah portion, after “the children of Israel were going out beyad ramah“, the pharaoh sends a troop of charioteers after them.

And Pharaoh came closer, and the children of Israel raised their eyes, and hey! Egyptians! Pulling out after them! And they were very frightened, and the Children of Israel cried out to God. And they said to Moses: “Are there no graves in Egypt, that you take us to die in the wilderness? What is this you have done to us, to take us out from Egypt?” (Exodus 14:10-11)

At once the Israelites are struck with fear of their old owners, the bullies who tortured and subjugated them. They cry out to God, but there is no immediate response. Their belief in God’s protection is too new and fragile to withstand their reflexive fear. They cringe and despair. They are caught between the sea and the chariots. At that moment, they think they will always be victims.

Yet when they complain to Moses, they make a sarcastic joke: “Are there no graves in Egypt, that you take us to die in the wilderness?” Thus Jewish humor is born.

*

Would you rather be an arrogant bully, like the pharaoh in the book of Exodus, treating people with high-handed disregard, too habitually hard-hearted to learn compassion?

Or would you rather be like an Israelite in Egypt, never certain of your status and power—but resilient enough to keep your sense of humor? If so, then be careful about when you act with “a high hand”.

—

- Exodus 13:17-18.