Go to Jerusalem! That’s where God wants to be worshiped!

This message is repeated insistently in both this week’s Torah portion, Re-eih (Deuteronomy 11:26-16:17) and in the haftarah reading, the “Third Haftarah of Consolation” from Second Isaiah1 (Isaiah 54:11-55:5).

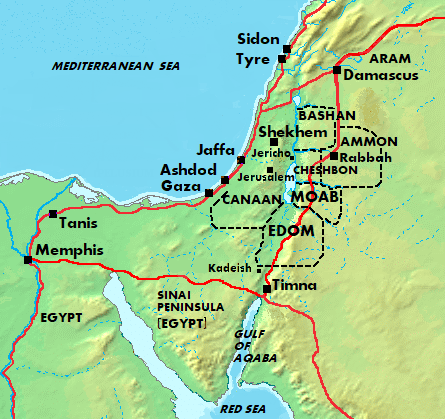

Moses is addressing the Israelites who have spent forty years in the wilderness after leaving Egypt, and are finally about to cross the river and conquer Canaan. He promises in this week’s Torah portion that God will grant them security on their new homeland. Then, he says, they must all travel three times a year to one place, “the place that God will choose”, to worship God with burnt offerings and gifts to the priesthood. Although Deuteronomy does not say where that place will be, the writers of even the first draft of that book in the 7th century B.C.E. knew the exact location: the temple in Jerusalem.

The poet called Second Isaiah is addressing the Israelites who were deported to Babylon in the 6th century B.C.E. He promises in this week’s haftarah reading that God will grant them security on their old homeland. Then, he says, they must rebuild the temple in Jerusalem and worship God there.

Deuteronomy: The place that God will choose

The Hebrew Bible is full of commands to worship only the God of Israel and no other gods or idols. This week’s Torah portion adds that the places where other gods were once worshiped are forbidden as worship sites, and even the names of those places must be changed.

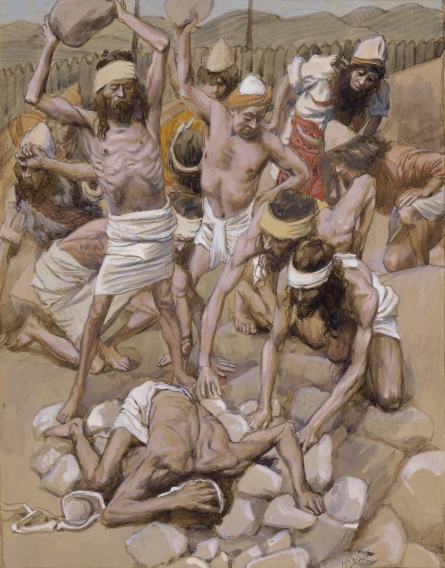

You must definitely demolish all the places where the nations that you will dispossess served their gods: on high mountains and on hills and under any verdant tree. And you must tear down their altars, and you must smash their standing-stones, and ashereyhem you must burn in fire, and you must chop up the carved idols of their gods; and you must eradicate their name from that place. (Deuteronomy 12:2-3)

ashereyhem (אֲשֵׁרֵיהֶם) = their trees or wooden poles used as idols for the goddess Asherah.

Then Moses says, ambiguously:

You must not do likewise for God, your God. (Deuteronomy 12:4)

The Talmudic rabbis in the 5th century C.E. said this means the Israelites must not eradicate God’s name, i.e. erase the name of God from any writings. Rashi (Rabbi Shlomoh Yitzchaki) in the 11th century wrote that this verse also meant you must not burn offerings to God at any place you choose, but only at the place God chooses.

This restriction on the place of worship will begin after the Israelites have conquered Canaan and are secure in their new land.

And you will cross the Jordan and you will settle down in the land that God, your God, is giving you as a possession, and [God] will give you rest from all your enemies all around, and you will settle down in security. Then it will be to the place that God, your God, chooses to have [God’s] name dwell that you will bring everything that I command you: your rising-offerings and your slaughter-offerings, your tithes and the contributions of your hands, and all the choice vow-offerings that you vow to God. (Deuteronomy 12:10-11)

It would be unreasonable to expect people to leave their farms for trips to Jerusalem and back if they had to worry about enemy raids, so Moses reassures the people that God will grant them safety. The last chapter of the portion Re-eih describes the three annual festivals when the people must bring these things to “the place that God will choose”.

Three times in the year all your males must appear in front of God, your God, at the place that [God] will choose: at the festival of matzah, and the festival of Shavuot, and the festival of Sukkot. And they must not appear in front of God empty-handed. (Deuteronomy 16:16)

Worship at the place (the temple in Jerusalem) is obligatory. But Moses also makes the festivals in Jerusalem sound, well, festive.

And you will rejoice before God, your God—you and your sons and your daughters and your male slaves and your female slaves—and the Levite who is within your gates, since he has no portion of land among you. Watch yourself, lest you bring up [the smoke of] your rising-offerings in [just] any place that you see! (Deuteronomy 12:12-13)

The rejoicing includes feasting; the donors of most types of sacrifices get a portion of the roasted meat to share. The portion Re-eih continues the Torah’s concern with making sure everyone eats well, including slaves and the religious officials (Levites) who have no land of their own to farm. But it also emphasizes the importance of bringing offerings to “the place that God will choose”: Jerusalem, the center of government and religion for the kingdom of Judah.

Isaiah: the place that God already chose

This week’s haftarah is an excerpt from a longer section of Second Isaiah tin which God addresses Jerusalem personified as a woman. The address begins:

Awake, awake, dress yourself in your strength, Zion!

Clothe yourself in your splendor, Jerusalem, holy city! (Isaiah 52:1)

This week’s haftarah reading picks up with God’s poetic description of Jerusalem as a desolate woman.

Wretched, storm-tossed one, not consoled! (Isaiah 54:11)

Jerusalem is miserable because the Babylonian army tore down her city walls and her temple, and deported her “children” (citizens) to Babylon. But God promises Jerusalem that she will be rebuilt—not with stones, but with gems.

And all your children will be God’s disciples,

And they will have abundant well-being. (Isaiah 54:13)

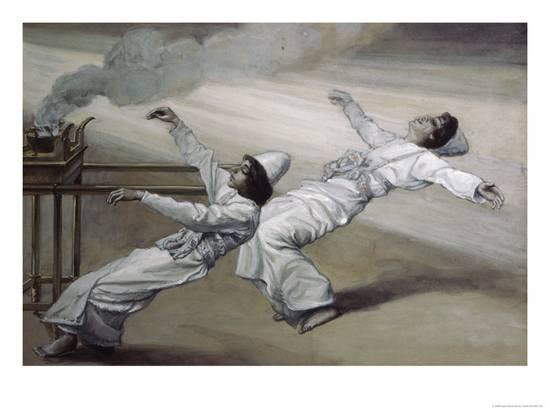

The reason why God let the Babylonians take Jerusalem in 587 B.C.E., according to the Isaiah, Jeremiah, and Ezekiel, was that its citizens were flagrantly violating God’s rules, both by worshiping other gods and by oppressing the poor. Here Second Isaiah prophesies that when the exiles (Jerusalem’s “children”) return, they will behave quite differently; they will be dedicated to learning God’s laws. Therefore, instead of sending in an enemy army, God will grant the Israelites of Jerusalem peace and prosperity.

Through tzedakah you will be established.

You will be distant from oppression,

So that you will not be afraid,

Because ruin will not come near you. (Isaiah 54:14)

tzedakah (צְדָקָה) = righteousness, honesty, justice.

Righteous people are “distant from oppression” because they do not commit it—regardless of whether others are oppressing them or not. Will their righteousness make them unafraid? Or is it God’s promise to keep ruin away that will give them courage?

The late Rabbi Steinsalz explained that the verse means:

“…you will be rebuilt on a foundation of honesty and justice. Distance yourself from exploitation, for you need not fear. Sometimes, one acts dishonestly out of fear. Since you will live in tranquility, you will be capable of distancing yourselves from such behavior.”2

In the next verse, God says that the people will be secure because God will make sure the only force that has any power over them is God itself.

Hey, definitely nothing will attack unless it is from me;

Whoever would attack would fall over you. (Isaiah 54:15)

… This is the portion of God’s servants,

And their tzedek is through me, declares God. (Isaiah 54:17)

tzedek (צֶדֶק) = what is right, what is just; vindication. (From the same root as tzedakah.)

“And their tzedek is through me” could mean that doing the right thing always involves serving God. Or it could mean that God will inspire them to do the right thing. The haftarah goes on to urge the Israelites to choose the nourishment of God’s covenant over the material advantages of staying in Babylon. (See my post: Haftarat Re-eih—Isaiah: Drink Up.) Second Isaiah knows the exiles will choose to travel to Jerusalem and renew the covenant only if they are no longer afraid of either human enemies, or their own God.

Both the Torah portion and the haftarah urge the people to stick to worshiping only their own God. Both also say they must worship God in the place God chose: Jerusalem.

Why is Jerusalem so important? Since God created the whole world, why can’t the Israelites worship God anywhere?

In the Hebrew Bible the Israelites are constantly tempted to worship the gods of other places. Insisting on worship in Jerusalem, where God’s temple was located for many centuries, is one way of reinforcing the worship of only one god.

In the books of Ezra and Nehemiah, at least two parties of Israelites do move from Babylon back to the ruins of Jerusalem, rebuild the city walls, and build a second temple for God, which lasted from around 500 B.C.E. until the Roman destruction of the temple in 70 C.E.3

Since then, for almost two millennia, Jews have worshiped God in every place they lived, all over the world—through prayers rather than animal sacrifices. Yet in our liturgy we still hope to return to Jerusalem personally, not just as a people. Actually moving there (“making aliyah”, ascent) is considered especially virtuous, but visiting is also good.

I finally visited Jerusalem myself in early 2020 (and left sooner than I had planned because of the Covid pandemic). Twice I stood at the Western Wall (Kotel)4 and prayed, grateful that at least there is a section of the wall designated for women now.

I have friends who felt the presence of God when they stood at the Wall. But I did not, despite my excitement over actually being there. The only times I have felt God’s presence have been when I was singing prayers with my congregation, or whispering prayers as I walked alone in the forest.

The writers of Deuteronomy and Second Isaiah probably took the best approach to bring people at that time (around the 6th century B.C.E.) closer to God and tzedek. But please don’t give me that old time religion.

- The first 39 chapters of Isaiah record the prophecies of Isaiah (Yesheyahu) son of Amotz, who lived in the 8th and 7th centuries B.C.E. Second Isaiah (also called Deutero-Isaiah) was appended to the original book, and records the poetry of an unknown prophet who prophesied in the 6th century B.C.E. after the Persians had conquered the Babylonians and give the exiles in Babylon permission to return to their homelands.

- Rabbi Adin Even-Israel Steinsaltz, The Steinsaltz Nevi-im, Koren Publishers, Jerusalem, 2016, quoted in www.sefaria.org.

- Herod saved key elements from the second temple when he rebuilt it on a grander scale in the first century B.C.E.

- The Western Wall, formerly called the Wailing Wall, is the only structure left from Herod’s temple. It was a high, thick foundation wall around the Temple Mount which was then backfilled and topped with a large stone platform. The temple and its associated buildings and stairs were erected on that platform.