Below is the fourth and final post in my series on the relationship between Avraham (“Abraham” in English) with God. If you want to read one of my posts on this week’s Torah portion, you might try Toledot: Rebecca Gets It Wrong.

The book of Genesis/Bereishit portrays both Avraham and God as complex characters, and their relationship evolves slowly. It begins when God tells Avraham to leave his home and go to the land of Canaan, making the first of many promises that Avraham will have a whole nation of descendants who own that land.1 Avraham simply obeys. After that he makes his own decisions about where to live and what to do, while God repeats the promises about his descendants,2 and makes sure that his wife, Sarah, is returned to him after Avraham scams two kings.3

At the third repetition of the promise of descendants, Avraham begins asking God for guarantees. (See my post Lekh-Lekha: Conversation.) The God character responds first with a treaty ceremony,4 then with a two-way covenant in which God gives Canaan to Avraham and his descendants, and Avraham and his male descendants will be circumcised.5 (See my post Bereishit, Lekh-Lekha, and Vayeira: Talking Back.)

Later, God takes their relationship a step further by telling Avraham ahead of time about the plan to wipe out the valley of Sodom.6 Avraham responds by making a strong ethical argument for pardoning Sodom for the sake of the innocent people living there, and God agrees to do it if there are even ten. (See my post Vayeira: Persuasion).

Many years after that, God tells Avraham to slaughter and burn his own son as an offering. And Avraham silently obeys. It seems as if both characters are seized by sudden madness. Why do they act this way?

Your only one, whom you love

The story, which Jews call the Akeidah (עַקֵידָה = “Binding”), begins:

And it was after these events, and God nisah Avraham, and said to him: “Avraham!” And he said: “Here I am.” (Genesis 22:1)

nisah (נִסָּה) = tested, evaluated, assayed.

From the beginning, we know the Akeidah is a test, but we do not know what result God is hoping for.

And [God] said: “Take, please, your son. Your only one, whom you love. Yitzchak. …” (Genesis 22:2)

Avraham has two sons. Hagar, his slave or concubine, bore him the elder one, Yishmael (“Ishmael “in English), and Sarah, Avraham’s wife, bore him the younger one, Yitzchak (“Isaac” in English). “Your only one” is a reminder that only Yitzchak is still part of Avraham’s household, and only Yitzchak is destined to have the descendants who inherit Canaan.

Perhaps God also needs to remind Avraham that he loves Yitzchak. Earlier in the Torah Avraham goes to some trouble for his nephew Lot,7 and feels love and concern for his older son, Yishmael.8 But it does not mention Avraham showing any feelings or making efforts for Yitzchak.

Perhaps Avraham demonstrates no special attachment to Yitzchak because there is no occasion to rescue him or worry about him—until God orders him:

“Take your son … And go for yourself to the land of the Moriyah, and offer him up there as a burnt-offering on one of the hills, which I will say to you.” (Genesis 22:2)

Moriyah (מֺרִיָּה) = mori (מֺרִי) = my showing, my teacher + yah (יָה) = God; therefore Moriyah = God is showing me, God is my teacher.

The name of the land implies that God will be not only testing Avraham, but teaching him something.

Offer him up

Slaughtering one’s own child as an offering to a god was not unknown in the Ancient Near East, but it was a rare and desperate move. Within the Hebrew Bible, the king of Moav sacrifices his oldest son so that his god will help him defeat the Israelites.9 But Genesis 22:2 is the only time that the God of Israel asks for a human burnt offering.

Avraham does not question this shocking order from God. Although he used an ethical argument to persuade God to refrain from destroying Sodom, now he says nothing at all, even though Yitzchak is innocent of any crime.

Avraham’s silence also ignores the fact that Yitzchak is still unmarried and childless, and God promised him many descendants through Sarah’s son.

And Avraham got up early in the morning, and he saddled his donkey, and he took two of his servants with him and his son Yitzchak, and he split wood for the burnt-offering, and he stood up, and he went to the place that God said. On the third day, Avraham raised his eyes and saw the place from a distance. (Genesis 22:3-4)

He does not tell either his servants or his son about God’s command during those three days. When they arrive, Avraham orders the servants to wait at the foot of the hill until “we will return to you.” (Genesis 22:5) As father and son are walking to the top, Yitzchak asks him where the lamb is for the offering, and Avraham says God will see to it. Perhaps he is lying, or perhaps he believes that at the last minute God will indeed provide a lamb to replace Yitzchak, and they will come back down together.

Once the wood is on the altar, Avraham can no longer conceal God’s command. And apparently Yitzchak accepts it, since at that time he is either 26 or 37 years old,10 and his father is 126 or 137 years old. Clearly the younger man is offering no resistance.

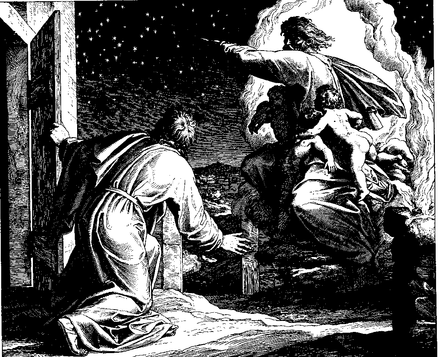

And Avraham reached out his hand, and he took the knife to slaughter his son. Then a messenger of God called to him from the heavens, and said: “Avraham! Avraham!” And he said: “Here I am.” (Genesis 22:10-11)

In the Hebrew Bible, a messenger of God (sometimes called an “angel” in English translations) may or may not be visible, but it always has a voice through which God speaks. The last words Avraham ever says to God in the Torah are his answer to the messenger: “Here I am”.

And [the messenger] said: “Don’t you reach out your hand toward the young man. Don’t you do anything to him! Because now I know that you are yarei God; you have not withheld your son, your only one, from me.” (Genesis 22:12)

yarei (יָרֵא) = in fear of, in awe of, reverent of.

Perhaps God’s test is to find out how much Avraham is in awe of God.

Only then does Avraham see a ram caught in a thicket behind him. He uses it as the burnt offering in place of Yitzchak.

Then the messenger of God called to Avraham a second time from the heavens, and said: “By myself I swear, word of God, that since you did this thing, and did not withhold your son, your only one, from me, I will bless you and definitely multiply your descendants like the stars of the heavens and like the sand that is on the shore of the sea, and your descendants will possess the gates of their enemies. And they will bless themselves through your descendants, all the nations of the earth, as a consequence of your heeding my voice!” (Genesis 22:15-18)

This second speech repeats the promises God has been making ever since the call to leave home and go to Canaan, but now they are framed as a reward for Avraham’s obedience to God’s outrageous command.

Then Avraham returned to his servants, and they got up and went together to Beirsheva, and Avraham stayed in Beirsheva. (Genesis 22:19)

The text does not say that Yitzchak returned with Avraham. In the next Torah portion, Chayei Sarah, Avraham sends his steward to bring a bride to Yitzchak, who is living on his own at Beir-lachai-roi. He evidently knows it is useless to try to summon his son to his own encampment. Father and son are not in the same place again until Avraham dies at age 175, and Yitzchak and Yishmael come and bury him.11

Neither God, nor Yitzchak, nor Yishmael ever speaks to Avraham again. To me this indicates that even if Avraham passes God’s test, he does not earn flying colors.

The test

Jewish commentary is rich with theories about what God’s test is, and whether Avraham really passes it or not.

Does God want to know whether Avraham values obedience to God over love, reason, or ethics? (And if so, what does God want him to put first?)

Does God want to know if Avraham has enough compassion for Yitzchak to draw the line?13

Does God want to know whether Avraham believes that God would never expect him to do something evil?14 (And if so, does passing the test mean refusing to obey, or proceeding and assuming God will stop him at the last minute?) Or does God want to know whether Avraham can live with a clear contradiction—between God’s promises of many descendants through Yitzchak, and God’s command to slaughter Yitzchak while he is still childless?15 (And if so, does living with the contradiction count as passing the test or failing it?)

The silence

Why does Avraham revert to silent obedience when God orders him to slaughter Yitzchak as an offering?

He would never have argued with God about Sodom unless he believed in justice for the innocent. Yet he prepares to slaughter Yitzchak despite his ethical principles.

Is his compassion too limited? Does he feel more responsible for Lot than for Yitzchak? Is his heart too small to love more than one son?

Does he intuit that God’s contradictory command is a test, and decide to test God in return by silent obedience? If the divine messenger had not stopped him, would he have actually plunged in the knife?

Or is Avraham simply too old to figure out how to handle a radically new situation? The God character is able to try something new, but perhaps Avraham is no longer able to respond with anything but his usual obedience.

It would have been kinder if the God character had appreciated what Avraham had already achieved as the father of a new nation, and saved the ultimate test for one of his descendants.

- Genesis 12:1-3.

- The promises occur in Genesis 12:7, 13:14-17, 15:1-5, 15:7, 15:18,17:1-8, and 22:17-18.

- Genesis 12:17-19 and 20:3-7. See my posts Lekh-Lekha, Vayeira, & Toledot: The Wife-Sister Trick, Part 1 and Part 2.)

- Genesis 15:7-21.

- Genesis 17:1-27.

- Genesis 18:17-21.

- Genesis 12:5, 13:8-12, 14:12-16.

- Genesis 21:11. See my post Vayeira: Failure of Empathy.

- 2 Kings 3:26-67. Also see Jeremiah 19:5.

- Yitzchak is old enough to carry a load of firewood for his aging father, and is called a na–ar (נַעַר), a boy or unmarried young man. He is younger than 40, because at that age he is living away from his father and marries Rivkah (Rebecca). The two most common opinions in the commentary are that Yitzchak is either 26 or 37.

- Genesis 25:7-9.

- See Marsha Mirkin, “Reinterpreting the Binding of Isaac”, Tikkun, Vol. 18, No. 5, 2003.

- See David Kasher, ParshaNut: Parshat Vayera: “It’s Complicated”, 2104; and Elimelekh of Lizhensk, Noam Elimelekh, 1786. Also see Martin Buber, Eclipse of God: Studies in the Relation Between Religion and Philosophy, 1957; and .

- See Jonathan Sacks, Covenant & Conversation, “Negative Capability: Vayera 5780”, 2019; and Soren Kierkegaard, Fear and Trembling, 1843.