Humans have always wanted to improve their odds for a good future. In biblical times, people stored extra grain in case next year’s crop was bad; today we can put part of our paycheck into savings. In biblical times, people followed religious rules so God would not smite them with disease; today we can get vaccinations.

And some people have always tried to beat the odds with occult practices, practices that others believe are either ridiculous acts or religious violations.

This week’s Torah portion, Shoftim (Deuteronomy 16:18-21:9), includes an instruction that denounces nine occult practices, five of which were performed in order to divine the future. That passage begins:

When you enter the land that God, your god, is giving to you, you must not learn to act according to the to-avot of those nations. (Deuteronomy/Devarim 18:9)

to-avot (תּוֹעֲבֺת) = plural of to-eivah (תּוֹעֵבָה) = taboo; an abomination, a foreign perversion, a custom in one culture that is prohibited in another culture.

Biblical Hebrew uses the word to-eivah almost like the English word “taboo” (which comes from the Tongan word tabu = set apart, forbidden). Actions (or topics of conversation) that are to-eivah in the bible and taboo in English usage are prohibited because they violate social, moral, or religious norms. These violations incite strong negative emotional reactions. In the bible either God, or people belonging to a certain religious or ethnic group might react with visceral repugnance. (See my post Shoftim: Abominable.)

Moses uses the word to-eivah sixteen times in the book of Deuteronomy, as he forbids a variety of activities that violate Israelite cultural, moral, or religious norms. Half of these verses explicitly refer to worshiping Canaanite gods, including two verses in the Torah portion Shoftim.1 This week’s Torah portion also calls sacrificing a defective animal to the God of Israel to-eivah.2

Then there are two verses in the portion Shoftim that forbid the Israelites to copy the to-avot of the Canaanites in the land they are about to conquer.3 These two verses bracket a list of nine types of practitioners of abhorrent magic:

There shall not be found among you one who makes his son or his daughter go across through the fire; a koseim kesomim, a meonein, or a menacheish; a mekhasheif or a choveir chaver; or one who inquires of ov or yidoni, or one who seeks the dead. (Deuteronomy 18:10-11)

Since many of the Hebrew words are almost untranslatable, we will consider one category at a time. Part 1 this week will examine making your offspring cross the fire, then three different types of divination. Part 2 next week will examine the sorcery of a mekhasheif and a choveir, then three types of necromancy.

One who makes his son or daughter cross the fire

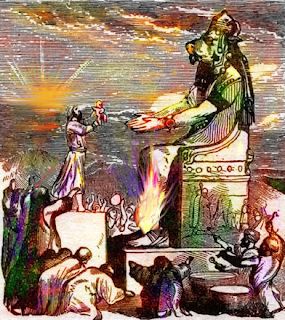

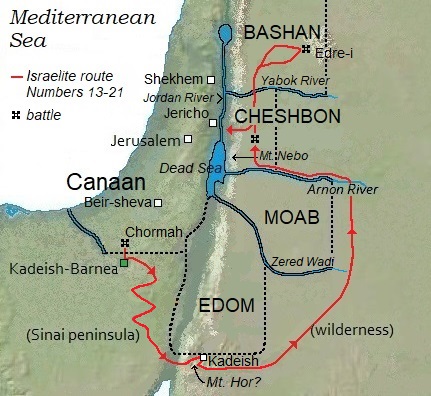

The first to-eivah practice is making your son or daughter “go across through the fire”. According to the books of Leviticus, 1 Kings, Jeremiah, and 2 Chronicles, some Israelites gave their offspring to an Ammonite god called Milkom or Molekh in a ritual that included crossing through fire. This took place in the Valley of Ben-Hinom, just outside the southern wall of the city of Jerusalem.4

It is not clear whether this ritual was a dramatic initiation ceremony, an ordeal by fire that could be survived, or a form of human sacrifice. Whatever happened, making your offspring pass through the fire would be to-eivah on religious grounds, since God prohibits the worship of idols and/or other gods throughout the bible, comparing it to prostitution and finding it abominable.

A diviner: Koseim

Next Moses lists three types of people who are to-eivah because they engage in divination. The first is a:

koseim kesomim (קֺסֵם קְסָמִים) = diviner of divinations. (The root verb is kasam, קָסַם = practice divination.)

What type of divinations are kesomim? Although words from the root kasam appear 33 times in the Hebrew Bible, there is only one verse that offers any clues about how it is done. In this verse, God describes the king of Babylon wondering whether to send his army to conquer the city of Rabah in Ammon, or the city of Jerusalem in Judah. God tells the prophet Ezekiel:

For the king of Babylon stood at a fork in the road, at the starting point of the two roads, liksam kesem; he shook arrows, he inquired of figurines, he looked into a liver [the organ in an animal]. (Ezekiel 21:26)

liksam (לִקְסָם) = to divine.

kesem (קֶסֶם) = a divination (singular of kesomim).

When Moses refers to kesomim in this week’s Torah portion, the divination technique might be any of these three.

A diviner: Meonein

Meonein (מְעוֹנֵן) = diviner. The verb is onein (עוֹנֵן) = cause something to appear, conjure up a spirit, practice magic. This verb is closely related to the noun anan (עָנָן) = cloud. Did a meonein divine the future by reading clouds? Or by conjuring spirits?

The only hint in the bible is that first Isaiah denounces the Israelites for practicing magic including “onenim like the Philistines”. (Isaiah 2:6)

onenim (עֺנְנִים) = making things appear. (A plural participle form of onein.)

But we do not know what sort of things the Philistines made appear, or how they did it.

A diviner: Menacheish

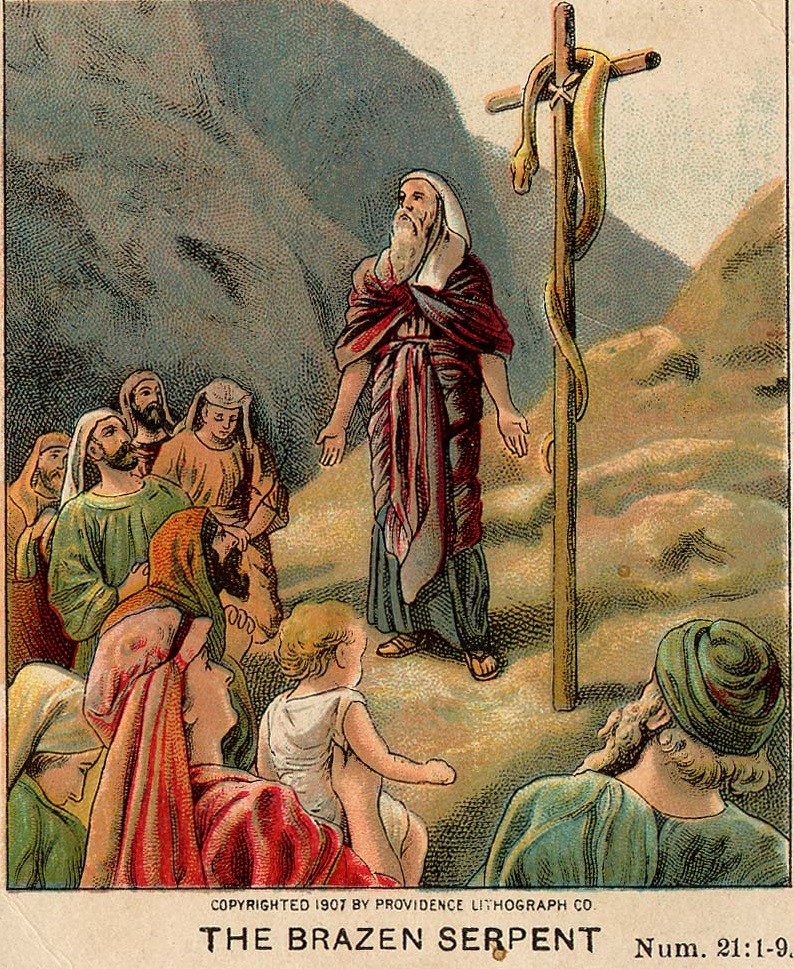

Menacheish (מְנַחֵשׁ) = diviner. The verb is nachash (נַחַשׁ) = practice divination. This verb is closely related to the noun nachash (נָחַשׁ) = snake. In ancient Greece, female diviners went into trances with the help of snake venom. We do not know if there was a similar practice in Canaan.

When Joseph is a viceroy of Egypt in the book of Genesis, he pretends to his brothers that he uses a silver goblet for divination, using the phrase nacheish yenacheish (נַחֵשׁ יְנַחֵשׁ) = “he definitely does divination”.5 This could mean that a menacheish did divination by reading the dregs in a cup—if it does not mean divination by drinking something hallucinogenic.

Not all divination is to-eivah

Although these three forms of divination are to-avot, the Hebrew Bible does not object to divination per se. Casting lots and answering yes-or-no questions using two objects in a priest’s vestments both win the bible’s wholehearted approval—when they are done under the right circumstances. For example, on Yom Kippur, the high priest is required to place lots on the heads two identical goats in the temple courtyard.

And Aaron must place goralot on the two hairy goats, one goral marked for God, and one goral for Azazeil. (Leviticus 16:8)

goralot (גֺּרָלוֹת) = plural of goral (גּוֹרָל) = a lot, something drawn from a container or tossed onto a marked surface in order to determine a decision; an allotted portion.

According to the Talmud, the two goralot used on Yom Kippur were made out of boxwood at first, then of gold.6 One was engraved with the name of God, and one with the name Azazeil. The high priest drew them out of an urn and placed one on each goat’s head. The goat that got the goral with God’s name on it was slaughtered, and its blood sprinkled in the Holy of Holies. The goat that got the goral with Azazeil on it was sent off into the wilderness after the high priest had transferred the sins of the Israelites to the “scapegoat”.7

After the Israelites conquer much of Canaan in the book of Joshua, Joshua casts lots to allocate territories to the seven tribes that have not yet claimed land, and parcels of land to the clans within each tribe.8 The word for “lot” is goral here, as well. The goralot are cast to match the tribes or clans to written descriptions of the lands.

Whether goralot were gold tokens or pebbles, what mattered was that no human being could determine the outcome of drawing or throwing lots. An outcome that many modern people would call random was, in the Hebrew Bible, a clear sign of God’s choice.

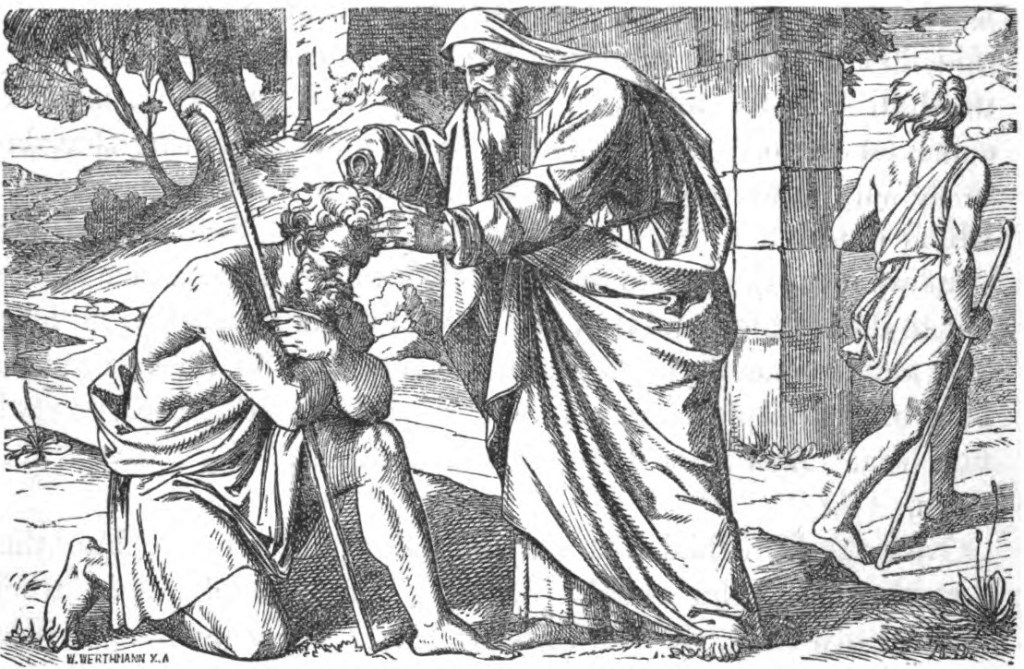

Another biblically approved method of divination was consulting the urim and tumim in the inside pocket of the high priest’s breast-piece, a key item in his elaborate vestments. These two mysterious objects are introduced in the book of Exodus, when God describes the vestments to Moses.

And you must place in the breast-piece of the rulings the urim and the tumim, and they will be over Aaron’s heart when he comes before God. (Exodus 28:29-30)

urim (אוּרִים) = an item in the pocket of the breast-piece. All we know is that is was small enough to fit, and that the word urim may—or may not—be related to the verb or (אוֹר) = become bright, illuminate.

tumim (תֻּמִּים) = an item in the pocket of the breast-piece. All we know is that is was small enough to fit, and that the word tumim may—or may not—be related to the adjective tamim (תָּמִם) = whole, complete, intact, unblemished, honest, perfect.

There are no clues in the Hebrew Bible about what the urim or the tumim look like, or how the high priest used them.

The book of Numbers says that when Joshua leads the Israelites to conquer Canaan, the high priest Elazar should consult the urim and tumim in front of God, and tell Joshua when to go out to battle and when to return.9 God will communicate through these objects.

In the first book of Samuel, King Saul tries, and fails, to get an answer from the urim about his upcoming battle against the Philistines.

And Saul saw the camp of the Philistines, and he was afraid and his heart trembled very much. Then Saul inquired of God, but God did not answer, either through dreams, or through the urim, or through prophets. (1 Samuel 28:5-6)

These inquiries are perfectly acceptable ways to ask God about the future. Saul’s unacceptable behavior is when he sneaks off to the “witch of Endor”, a woman who inquires of the dead, and asks her to raise the ghost of the deceased prophet Samuel. We will look into that story next week, in Shoftim: Is Magic Abominable?—Part 2, when we consider the last five kinds of magic in Moses’ list of occult practices that are to-avot.

- In the portion Shoftim: Deuteronomy 17:4 and 20:18. In other portions of the book: Deuteronomy 7:25, 7:26, 12:31 (including offering children in fire to other gods), 13:15, 27:15, and 32:16.

- Deuteronomy 17:1.

- Deuteronomy 18:9 (above) and Deuteronomy 18:12.

- Leviticus 18:21, 20:2; 1 Kings 23:10; Jeremiah 7:30-31, 32:34-35; 2 Chronicles 28:1-3, 33:5-6. See my post Acharey Mot & Kedoshim: Fire of the Molekh.

- Genesis 44:5 and 44:15.

- Talmud Yerushalmi, Yoma 3:7.

- Leviticus 16:5-10; . See my post Acharey Mot: Azazeil.

- Joshua 18:6-20:51.

- Numbers 27:21.