After the humorous story of the greedy Mesopotamian prophet Bilam and his talking donkey,1 Bilam delivers a series of poetic prophecies to King Balak of Moab in this week’s Torah portion, Balak (Numbers 22:2-25:9). Balak has promised to pay Bilam to curse the Israelites camped at his border, so he can defeat them if there is a battle. But Bilam is a true prophet, and can only utter a curse if God approves.

When Bilam arrives in Moab, he warns King Balak:

“Am I really able to speak anything at all? The speech that God puts in my mouth, only that can I speak.” (Numbers 22:38)

Then God proceeds to use Bilam as a mouthpiece for four prophecies. And every prophecy that mentions the Israelites blesses them instead of cursing them. Some of the blessings predict that the Israelites will destroy their enemies. (See my post: Balak & Micah: Divine Favor.) Others predict continued fertility and future abundance of resources.

The blessing of fertility

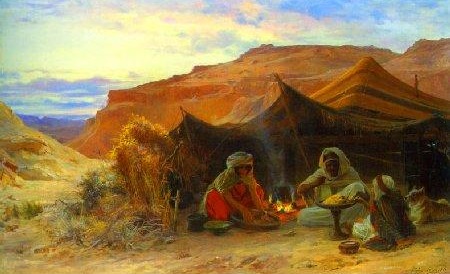

The dry climate of the Ancient Near East meant there was no natural surplus of food, and in the millennia before modern agricultural technology, it took intensive labor to till land, transport water, and bring in harvests. Fertile soil helped, and so did fecund livestock. But large families were also important, producing more people to do all the labor. In the book of Genesis, God commands humans three times to “Be fruitful and multiply”2. In Deuteronomy, the blessings humans can expect if they obey God include “the fruit of your womb, and the fruit of your soil, and the fruit of your livestock”3.

Bilam’s first prophecy in this week’s Torah portion says that God has already blessed the Israelites; the evidence is that they have multiplied until they cannot be counted.

How could I curse

Where God has not cursed?

How could I denounce

Where God has not denounced?

For from the top of cliffs I can see them,

And from hills I can observe them.

Here a people dwells alone

And it does not count itself among the nations.

Who can number the dust of Jacob,

Or reckon a quarter of Israel? (Numbers 23:8-10)

The blessing of water in Balak

Water was the most critical requirement for fruitful land in the Ancient Near East, since rain was not abundant and fell mostly during winter. (Egypt was so dry that crops depended exclusively on water from the Nile.) In Deuteronomy, Moses reminds the Israelites that “God, your God, is bringing you to a good land, a land with streams of water, pools, and springs going out from valley and hill”.4 Canaan did indeed have more natural sources of water, as well as some winter rain. But water was still a limiting factor for agriculture.

In one of Bilam’s prophecies (the third out of four), he praises the Israelites with a couplet still used in today’s Jewish liturgy, then compares the Israelites’ homes to well-watered land.

Mah tovu, your tents, Jacob

Your dwellings, Israel!

Like palm-groves they stretch out

Like gardens beside a river,

Like aloes planted by God,

Like cedars beside the water.

Water drips from their branches

And their seeds have abundant water. (Numbers 24:5-7)

Mah tovu (נַה־טֺּווּ) = How good they are. (Mah = what, how + tovu = they are good. A form of the adjective tov, טוֹב = good, i.e. desirable, useful, beautiful, or virtuous.)

The dwellings of the Israelites are good because they are desirable, like water. They are also good, according to 20th-century commentator Nehama Leibowitz, because the people living in them are virtuous.

Leibowitz cited four passages in the Hebrew Bible which use images of abundant water to indicate God’s reward for good behavior.5 Her best example is from second (or third) Isaiah:

If you remove the yoke from your midst,

Send away the pointing finger and the evil word,

And you extend yourself toward the hungry

And you satisfy the impoverished,

Then your light will shine in darkness

And your gloom will become like noon.

And God will give you rest always,

And satisfy your body in parched places,

And your bones will be strong,

And you will be like a well-watered garden,

And like a spring of water that does not disappoint,

Whose water never fails. (Isaiah 58:9-11)

The blessing of water in Micah

The haftarah reading that accompanies the Torah portion Balak is from the book of Micah. This reading begins with Micah’s prophecy for the Israelites (a.k.a. descendants of Jacob) who remain in what was once the northern kingdom of Israel before the Assyrian empire conquered it in 732-721 B.C.E. The Assyrians followed their usual strategy of deporting much of the native population to distant places, while moving other people into the newly conquered land.

Micah predicts what will happen to the small population of Israelites who are allowed to stay.

And it will be, the remnant of Jacob

In the midst of many peoples

Like dew from God,

Like gentle rain on grass,

That does not expect anything from a man,

And does not wait for human beings. (Micah 5:6)

Dew condenses regardless of what humans do, and the gentle rains of winter make grasses and grains grow without being watered by people. Micah’s implication, according to Rashi6 is that the remaining Israelites should not expect any help from other people, but God will help them. Micah goes on to predict that God will give “the remnant of Jacob” the strength of lions, the top predator in nature.7

Both fertility and water are powerful blessings in the Hebrew Bible. But human fertility is no longer a blessing today. Through overpopulation and pollution, we humans have created global climate change, making water even scarcer in dry regions while increasing flooding in the wetter parts of the world. The increase in dryness sets off larger forest fires, and the increase in extreme heat means humans, other animals, and plants need more water than before just to stay alive.

For all our advanced technology today, we cannot reverse the damage we have done; we can only hope to keep it from getting worse.

How can we keep it from getting worse? Yes, technology can help—but only if the powerful people of the world act not for their own selfish short-term profit, but for the welfare of all humankind, or indeed all life on earth. I wish the prophet in the book of Isaiah could enter the minds of all the decision-makers in corporations and governments, and persistently whisper: “extend yourself toward the hungry, and satisfy the impoverished”.

Only if the powerful decide in favor of life, rather than money or status, will we keep some remnant of “cedars beside the water”—as a metaphor, or in reality.

- See my post: Balak: Prophet and Donkey.

- Genesis 1:28, 9:1, 9:7, 35:11.

- Deuteronomy 28:4. 28:11, 30:9.

- Deuteronomy 8:7.

- Nehama Leibowitz, Studies in Bamidbar, trans. by Aryeh Newman, The World Zionist Organization, Jerusalem, 1980, p. 293. She cites Psalm 1:3, Jeremiah 17:8, Isaiah 58:11, and Jeremiah 31:12.

- Rashi is the acronym for 11th-century Rabbi Shlomoh Yitzchaki, the most cited classic Jewish commentator.

- See my post: Balak & Micah: Divine Favor.