Both army duty and sanctuary duty are dangerous in the Torah; they can result in death.

The book of Numbers (Bemidbar, “In the wilderness of”) opens when the people are preparing to leave Mount Sinai and conquer Canaan. So the first Torah portion, also called Bemidbar, begins with a census of all the Israelite men age 20 and over who can serve in the army. The twelve tribes of Israel1 are assigned campsites and marching positions by tribe. In the center of the camp is God’s Tent of Meeting, and in the center of the traveling troop are the disassembled parts of that tent.

The implication is that the Israelite men are protecting the Tent of Meeting from attack by local armed bands.

But the sanctuary itself is dangerous when God is in residence, and the holiest items inside it have power even when the tent is down. So God calls for a separate census of adult Levite men, who cannot serve in the army because their duty is to transport and safeguard the Tent of Meeting.

And when the mishkan is to set out, the Levites will take it down. And when the mishkan is in camp, the Levites will erect it. And the outsider who comes close yumat. (Numbers 1:51)

mishkan (מִשׁכָּן) = dwelling place of God; sanctuary. (From the root verb shakan, שָׁכַן = dwell, reside, live in, sojourn in, stop at.)

yumat (יוּמָת) = will be put to death. (A form of the verb meit, מות = die.)

When Israelites get too close

The outsiders who must not come too close to the mishkan include all the Israelites who are not Levites. Who will execute these outsiders? The classic commentators disagree, with Rashi’s camp claiming that “heaven” will smite the trespasser, and Ibn Ezra’s camp claiming that a human law court must sentence the trespasser to death.2

The Hebrew Bible provides only one example of this transgression, a story later in the book of Numbers. An Israelite man who is the chief’s son in the tribe of Shimon, and a Midianite woman who is the chief’s daughter in a tribe of Midian, walk right into the mishkan for a sexual ritual. A Levite named Pinchas spears them both, thereby executing the death penalty without the benefit of a trial. Then God tells Moses that if Pinchas had not acted so promptly, God’s rage would have destroyed the entire Israelite community.3

Given the danger of setting off God’s rage, the best strategy is to set a guard around the mishkan to intercept anyone who gets too close. And that is what this week’s Torah portion prescribes.

And the Levites will encamp around the mishkan of the Testimony,4 so that there will be no fury against the Israelites; and the Levites will observe the guard duty of the mishkan of the Testimony. (Numbers 1:53)

When Levites get too close

The campsites of the Levites are a buffer zone between the mishkan and the Israelites. The Levite clan of Merari camps along the north side of the Tent of Meeting, the clan of Gershon along the west side, and the clan of Kehat along the south side. The east side, which has the only entrance into the mishkan, is reserved for the tents Moses and the three priests: Aaron and his two surviving sons, Elazar and Itamar.

In front of the curtained entrance is a courtyard containing the copper altar, where animal and grain offerings are burned. Ordinary Israelites bring their offerings to this outdoor altar by entering the courtyard, so they must be allowed to come at least that close to the mishkan. But any Israelites who attempt to go past the altar and touch the curtain across the entrance must be put to death.

… and the outsider who comes close yumat. (Numbers 3:38)

Levites are allowed to touch the fabric of the tent, but only Moses and the priests can safely enter the Tent of Meeting.

Yet the Gershonite clan of Levites is responsible for taking down and setting up the entrance curtain, along with all the cloths forming the walls and roof of the mishkan. And the Merarites are responsible for disassembling and reassembling all the structural timbers and fasteners. How could they avoid stepping into the holy space inside?

Chizkuni5 explains: “They may not enter these holy precincts once the Tabernacle had been reassembled. Assembling or dissembling did not require their entering, and when the Tabernacle had been taken apart, the site it had stood on was no longer considered as a holy site.”

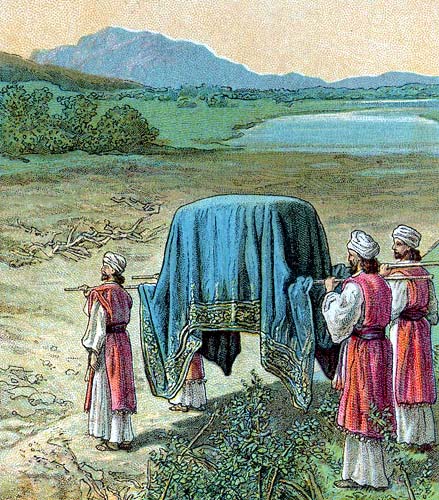

However, the objects inside the mishkan—the ark, the bread table, the lampstand, and the gold incense altar—are always holy. So before the tent is disassembled, the priests must cover these sacred objects, along with the tools used for their service, with multiple layers of cloth and leather, and place them on carrying poles or frames. (See my post Bemidbar: Covering the Sacred.) Only then are the Gershonites and Merarites allowed to take down the tent.

The Kehatite clan of Levites gets the duty of transporting the holy objects after the three priests have covered them.6

And Aaron and his sons are to finish covering the holy things and all the tools of the holy things at the breaking of camp. And after that, the Kehatites will come to lift them; and they must not touch the holy, vameitu. (Numbers 4:15)

vameitu (וָמֵתוּ) = or they will die. (Another form of the verb meit.)

Nobody except the three priests can touch the holy things themselves without dying. Furthermore, the Kehatites must not see the priests wrapping them.

And they must not come in to look as the holy things are swallowed up, vameitu. (Numbers 4:20)

The verses prohibiting the Kehatites from touching or looking at the holiest objects state that transgressors will die, not that they will be put to death. It would kill them to look at the holy objects while the priests are covering them. Does the Torah mean this literally?

Some commentators have argued that seeing the ark is deadly by citing a story in the first book of Samuel in which the two sons of the current high priest, Eli, bring the ark to the battlefield, where the Israelite soldiers raise a cheer. The sight of the ark does not kill them, but the Philistines do.7 The Philistines capture the ark and take it back to their own land, where it is moved from city to city. Each time the ark enters a new city, a plague strikes. Eventually the Philistines load the ark onto a wagon steered only by oxen, and send it back into Israelite territory. The oxen stop at the Israelite village of Beit Shemesh, and the men there look inside the ark. God strikes them dead for their lack of respect.8

Nobody dies from looking at the outside the of ark in that story.9 But in this week’s Torah portion, the Levites will die if they merely watch the priests cover up the ark and the other holy objects in the mishkan.

I wonder if their sudden terror at this unaccustomed sight would give them heart attacks. Or perhaps it is not their bodies that will die, but their souls. A soul radiant with awe is not the same as a soul divorced from all feeling.

When biblical scholars get too close

Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz compared the problem of the Levites in the Torah portion Bemidbar with the problem of recovering one’s religious awe after doing an analysis of the Torah and Talmud. He explained:

“As long as one stands at a distance from the sacred … one can see the sacred and stand in awe of it. But what happens when one has to dismantle the sacred? … It is a problem inherent in Torah study, in faith, and in Judaism: How can one question, take apart, demolish, and rebuild, and at the same time preserve the sense that one is in the realm of holiness? Only those who can bear it—the sons of Aaron, the Priests—may enter the inner Sanctuary and dismantle it. … Only one who does inner, hidden service, totally committed to serving God, may enter the Sanctuary and cover the sacred.”10

Human beings seem to need a sense that some thing or concept is sacred. Some people today feel that way about tangible things such as holy books or national flags. Some feel that way about a holy place. For others the most sacred thing is an idea—for example, an ethical imperative, a conception of God, or a belief in reason.

When someone violates or disgraces what you hold sacred, your emotional reaction is swift and negative. A patriot who considers the national flag sacred automatically labels flag-burning an abomination, and wants immediate punishment for the perpetrator. For some Jews, dropping a Torah scroll on the floor, even accidentally, causes shock and guilt; throwing one down deliberately would mean automatic de facto excommunication.

And if you hold an idea sacred, you automatically reject all arguments against it. But once in a while the unthinkable happens. A well-meaning outsider succeeds in persuading you that your sacred belief is a fallacy. Or an event in your life or in the world violates your whole conception of what is true. Then your loss is hard to bear, since a sacred thing gives life meaning.

In the Torah portion Bemidbar, for an unauthorized person to touch the mishkan when God is in residence, or to see its most sacred objects, results in the death penalty. In our lives today, the demolition of a sacred idea causes a psychological death, as the believer is swamped by a sudden loss of meaning.

May every person who has this experience be granted the strength and resilience of a Levite, or even a priest, and rebuild the sacred in a new place of wisdom.

- The Torah portion Bemidbar, as well as later Jewish tradition, distinguishes between three kinds of people for religious purposes: the priests (kohanim), who are an elite subset of Levites; the Levites (Levi-im), who are a tribe of Israel but not counted as part of the Israelites because they have specific religious functions; and the twelve tribes of Israelites (benei Yisrael), counting Joseph’s sons Efrayim and Menashe as two tribes and not counting the Levites.

- Rashi is the acronym for 11th-century Rabbi Shlomoh Yitzchaki. He explained that the fury in Numbers 1:53 refers to God executing outsiders who get too close to the tent. Ibn Ezra is the 12th-century rabbi Avraham ben Meir ibn Ezra.

- Numbers 25:6-15.

- The “testimony” (eidut, עֵדֻת) here is the pair of stone tablets inside the ark. The book of Exodus frequently refers to the ark of the testimony, while the book of Numbers refers nine times to the tent or mishkan of the testimony. (Numbers 1:50, 1:53 (twice), 9:15, 10:11, 17:19, 17:22, 17:23, and 18:2.)

- Rabbi Hezekiah ben Manoah compiled commentary in the book Chizkuni in 13th century.

- In addition, the priests cover and the Kehatites transport the copper altar where offerings are burned in the courtyard. See my post: Bemidbar & Naso: Why Cover the Altar?.

- 1 Samuel 4:3-11. See my post: Pekudei & 1 Kings: Is the Ark an Idol?.

- 1 Samuel 6:19; Talmud Bavli, Sota 35a-b.

- This has led some commentators to posit two arks, a mishkan ark and a battle ark—or at least two literary traditions about the ark.

- Adin Even-Israel Steinsaltz, Talks on the Parasha, Koren Publishers, Jerusalem, 2015, pp. 281-287.