Ta-da! A new place to worship God, and a new dwelling for God to inhabit!

Moses makes the ta-da moment happen when he assembles the first tent sanctuary and all its appurtenances in this week’s Torah portion, Pekudei (Exodus 38:21-40:38). King Solomon completes the first Israelite temple in Jerusalem1 in this week’s hafatarah (accompanying reading) in the Sefardic tradition, 1 Kings 7:40-50.

Although both the tent sanctuary and the temple use the same basic equipment for worship—ark, menorah, bread table, incense altar, wash basin, altar for burning offerings—the scale and the architecture are different. (See my post Haftarat Pekudei—1 Kings: More, Bigger, Better.) One outstanding difference is the entrance.

Grand entrance

The entrance of the sanctuary tent is framed in acacia wood. Instead of a door, there is a curtain embroidered with blue, purple, and crimson yarns.2

The entrance to the main hall of King Solomon’s temple has olive-wood doorposts and double doors of carved cypress wood covered with gold.3 But the most striking feature is the pair of gigantic bronze columns that Chiram casts and erects in front.

This is not King Chiram of the Phoenician city of Tyre, who provides Solomon with cedar and cypress wood for the temple. The Chiram who casts all the bronze is the son of an Israelite woman from the tribe of Naftali and a Tyrean bronzeworker.4

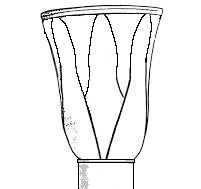

Bible Museum, Amsterdam

(with capitals that look like single

giant pomegranates)

And Chiram finished doing all the work that he did for King Solomon on the House of God: two amudim, and the globes of the capitals on top of the two amudim, and the two networks to cover the two globes of the capital on top of the amudim, and the four hundred pomegranates for the two networks—two rows of pomegranates for each network to cover the two globes of the capitals that were on the amudim. (1 Kings 7:40-42)

And all these things that Chiram made for King Solomon for the House of God were burnished bronze. (1 Kings 7:46)

amudim (עַמּוּדִים) = columns, pillars, posts, upright poles. (Singular amud, עַמּוּד, from the root verb amad, עָמַד = stood.)

Capital, capital

The Hebrew Bible is not averse to repetition. Shortly before this passage, the first book of Kings describes the impressive columns and their capitals in even more detail:

And he made two capitals to put on top of the amudim, cast in bronze. The one capital was five cubits high, and the second capital was five cubits high. [He made] networks of wreathes of chainwork for the capitals that were on top of the amudim, seven for one amud and seven for the second. And he made the pomegranates, with two rows encircling the network, to cover the capital on top of the first amud, and the same for the second one. (1 Kings 7:16-18)

In other words, the capitals of the columns are globes completely covered with a bronze decorative network in a pattern of chains and pomegranates. Each capital has seven chains and two rows of pomegranates.

The next verse in 1 Kings describes shorter capitals with a different kind of decoration.

And the capitals that were on top of the amudim in the portico were in a lily pattern, four cubits. (Exodus 7:19)

A four-cubit capital in a lily pattern (the design craved into the capitals of smaller stone columns archaeologists have found in Jerusalem) is quite different from a five-cubit capital covered with a network of chains and pomegranates. And the portico would require a number of columns to support its roof, since it extends across the entire front of the main hall, 20 cubits (30 feet), and it is 10 cubits (15 feet) deep.5

Is this verse an aside about stone columns of the portico, which are quite different from the two bronze columns Chiram makes? Or does each bronze column have not one, but two capitals stacked one above the other—one in a lily pattern and one a globe covered with chains and pomegranates?

Lost in translation

The next verse should give us a clue, but it is unusually difficult to translate. Since the syntax of Biblical Hebrew is different from the syntax of English, all translations have to rearrange the word order to make the English intelligible. In 1 Kings 7:20, it is hard to know where to place the word for “also”. And although it is a standard move to change “the capital the second” into “the second capital”, what that phrase refers to is ambiguous.

It does not help that two of the Hebrew words in 1 Kings 7:20 that indicate location, milumat and le-eiver, have multiple valid translations.

Here is the verse with the words translated literally and not rearranged at all:

And capitals upon two the amudim also above milumat the belly that le-eiver the network and the pomegranates 200 rows around on the capital the second. (1 Kings 7:20)

milumat (מִלְּעֻמַת) = near, side by side with, alongside of, parallel with, corresponding to, close beside.

le-eiver (לְעֵבֶר) = to one side, across, over against.

Here is the standard 1999 Jewish Publication Society (JPS) translation:6

So also the capitals upon the two columns [amudim] extended above and next to [milumat] the bulge that was beside [le-eiver] the network. There were 200 pomegranates in rows around the top of the second capital (i.e., each of the two capitals). (1 Kings 7:20)

This translation moves “also” to the beginning of the verse, making it imply “and another thing I want to say is”. It sounds as though the capitals are simultaneously above, and next to, and beside the network on the capitals, which is hard to imagine. And a JPS footnote claims that “the second capital” means “each of the two capitals”, as if the translators could not think of any other explanation for the final phrase.

Here is a 2013 translation by Robert Alter,7 who is generally more literal than the JPS and usually provides clear translations:

And the capitals on the two pillars [amudim] above as well, opposite [milumat] the curve that was over against [le-eiver] the net, and the pomegranates were in two hundred rows around on the second capital. (1 Kings 7:20)

Alter translates the Hebrew word gam (גַּם) as “as well” instead of “also”, but it still means little in that location in the sentence. And what does the word “above” mean when it comes before “as well”? The location of the capitals in relation to the bulge or curve (literally “belly”) is phrased differently, but still obscure. Where is this curve, and what is it connected to? Furthermore, Alter’s translation sounds as though the pomegranates were in two hundred rows on the second capital, but not the first. Yet the earlier description of the two pomegranate capitals had two rows of pomegranates on each one.

Here is a 2014 translation by Everett Fox,8 who is generally even more literal than Robert Alter:

And the capitals on the two columns were also above, close to [milumat] the bulging-section that was across from [le-eiver] the netting, and the pomegranates were two hundred in rows, all around the second capital. (I Kings 7:20)

Fox’s placement of the word “also” implies that the same two columns also have capitals above the previously-mentioned lily capitals. Presumably these upper capitals are the ones decorated with pomegranates. If so, the phrase “the second capital” is no longer puzzling; it refers not to the capital on the second column, but to the second capital on the same column. But “close to the bulging-section that was across from the netting” remains hard to visualize.

Taking some tips from Fox, here is my best effort at an English translation:

And the capitals on the two columns were also above, next to the rounded molding that was on one side of the network. And two hundred pomegranates were in rows all around the top of the second capital. (Exodus 7: 20)

And here is my explanation:

Each bronze column has two capitals. At the top of each column is a four-cubit capital with a lily design. On top of the lily capital is a rounded molding referred to as a belly. And on top of the molding is a second capital, a five-cubit capital in the form of a globe covered with a network of chains and pomegranates.

In the next verse, Chiram names the two bronze capitals. Immediately after that, the text says:

And up on top of the amudim was a lily design. And the work of the amudim was completed. (1 Kings 7:22)

This confirms that the lily capitals are part of the two gigantic bronze columns, not part of separate stone columns.

Why would anyone stack two capitals on top of a column? For the same reason the Ancient Greeks invented the Corinthian capital, which essential takes an Ionic capital and inserts two ranks of acanthus leaves in between the astragal molding at the bottom and the scrolled volutes at the top, and throws in a few acanthus flowers for good measure. Anything ornamental can be made even more ornamental.

In the case of the capitals on the bronze columns, Chiram began with the six-petalled lily that “served as the symbol of the Israelite monarchy during certain periods”9 Then he added the globes covered with bronze chains and hundreds of pomegranates, an unusual and showy design. A bronze artist that skilled could hardly resist showing off.

Chiram the bronzeworker and Solomon the king are well-matched. Every detail of the new temple is designed to look as impressive as possible. Solomon even has the stone walls of the main hall covered with cedar which is carved and then gilded.

His father, King David, fought for the kingdom of Israel and ruled from Jerusalem, but still used a tent as God’s sanctuary. King Solomon inherited his kingdom. He concentrated on building up commerce and wealth, acquiring even more wives and concubines than his father, and building an elaborate palace for himself and temple for God.

Why not erect two gigantic bronze columns in front of the temple, with ornamentation that goes over the top?

- The Jebusites who occupied Jerusalem before King David conquered part of it probably had their own shrine. Genesis 14:17-20 mentions a Jebusite priest-king named Malki-tzedek who blesses Abraham.

- Exodus 26:36.

- 1 Kings 6:33-35.

- 1 Kings 7:13.

- 1 Kings 6:2-3.

- JPS Hebrew-English Tanakh, The Jewish Publication Society, Philadelphia, 1999, p. 724.

- Robert Alter, Ancient Israel: The Former Prophets, W.W. Norton & Company, New York, 2013, p. 638

- Everett Fox, The Early Prophets, Schocken Books, New York, 2014, p. 602.

- Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz, Introductions to Tanakh: Prophets, on 1 Kings 7:19, reprinted in www.sefaria.org.